On September 13, 2024, a Federal Court Judge issued summary judgement against Donald Trump and his campaign in the long running copyright infringement dispute with Barbadian based musician Eddy Grant over the Trump campaign’s use of Grant’s song “Electric Avenue” in a Trump campaign video. 1 I have been following this case for a long time and have blogged about it previously. 2 To anyone who read the Judge’s initial ruling on Trump’s Motion to Dismiss, the ruling against Trump should not be surprising. The only real surprise is why the case got this far.

As I suggested in my previous blog post, the case should have quickly been settled. Yet for whatever reason, including Trump’s own pugnacious personality, it was not, and now it will cost him. According to the complaint, Grant is seeking $300,00 in statutory damages, the maximum for infringement of not only the song “Electric Avenue” but sound recording as well. 3 The attorney’s fees, for four years of litigation, will easily top the amount of damages. And Trump is personally liable for both amounts.

“It’s everything we asked for,” one of Grant’s lawyers, Brett Van Benthysen, told Business Insider. “100%.” 4

The real question is why litigate? This crops up time and time again in copyright cases, where copyright defendants take to the costly step of litigating such malleable issues as “fair use” when a simple settlement, or license fee for that matter, would resolve the issue once and for all and make it go away, for a lot less money. And for Trump, the result is the prospect of a very large judgment against him, creating a lot of negative publicity around him at a time when negative publicity is very much not in his best interest. To which we can add the recent injunction granted against Trump for his use of “Hold On, I’m Comin” and a lawsuit filed by The White Stripes over use of the song “Seven Nation Army.” 5

As I noted three years ago:

Many times, an [infringement claim] occurs when songs are used at campaign rallies. The composers feel that this is an implied endorsement. The campaigns usually rely on a license from the performing rights organizations. However, sometimes the use is in a campaign video, and since this is a “synchronization” use, it absolutely requires a license and absolutely requires permission, even in the internet age. 6

To this, Trump trots out the same fair use argument that got pummeled in the Court’s rejection of his Motion to Dismiss. Indeed, large sections of the Court’s opinion on summary judgement could have been cut and pasted from its previous ruling. For the fine details of that ruling, I invite you to read my previous blog post. 7

The only new matter Trump brings to the Court is the contention that the “Electric Avenue” sound recording was not properly registered with the U.S. Copyright Office.

Interestingly enough, there is no discussion about whether the “Electric Avenue” sound recording had to be registered with the Copyright Office in the first place. Eddy Grant was born in Ghana, raised in the UK, and presently resides in Barbados, 8 and as such is protected by the Berne Convention.

In that situation, according to the expert folks at the Copyright Alliance:

“A foreign author may bring a copyright infringement action in a U.S. district court without registering his or her work with the U.S. Copyright Office. However, a foreign author must register his or her work with the U.S. Copyright Office in order to obtain certain statutory benefits that are provided under the 1976 Copyright Act, such as the presumption of validity and the ability to claim statutory damages and attorney’s fees in an infringement action.” 9

So, Grant’s lawsuit would have been sustainable in any event. The real crux would be his ability to ask for statutory damages and attorneys fees, which he clearly is asking for.

Now, while the song “Electric Avenue” was registered for copyright in the U.S. in 1983, 10 it does not appear that the sound recording was registered until many years later. “Electric Avenue” was recorded at Grant’s studio in Barbados and he is the sole musician on the recording, so the sound recording copyright unquestionably belongs to him. The sound recordings rights to “Electric Avenue” (amongst others) were licensed to Warner Music UK in 2001 for a five-year period, and for a territory which included the United States. 11 During this agreement, a “Greatest Hits” compilation was released which included “Electric Avenue.” This collection of sound recordings was registered with the U.S. Copyright Office in 2002. 12 The license agreement expired in 2006, by which all rights reverted to Grant. 13

For his part, Trump contends the “Greatest Hits” registration was insufficient to register the component part of “Electric Avenue.” All of these arguments fail.

The Court cites to previous Second Circuit precedent that held:

“a publisher that filed collective works copyright registrations for issues of its magazine would have thereby obtained copyright registration for…the articles contained in the issue if the publisher owned the copyrights for those articles.” 14

The Court also notes that:

“[Trump argues] that the registration for a collective work does not include the registration for any previously published part but have failed to point out any case that supports that position.” 15

Not a good strategy.

Also in his answer, Trump asserted that he had “absolute presidential immunity” from Grant’s lawsuit. 16 This argument was apparently so ridiculous that it didn’t even merit discussion in the summary judgement opinion.

But once again, why litigate this issue when a quick settlement and a much smaller fee would have made the entire matter disappear from the public eye? Further, why not take the video down after the cease and desist letter? Why wait until a lawsuit is filed until the video is removed from the public eye?

I’m not alone in this thought. As my colleague David Newhoff wrote at the Illusion of More website:

“When I wrote about the Grant v. Trump copyright case on October 1, I was wrong about one thing: that Team Trump would quickly settle the matter as a relative storm in a teacup within the legal tornadoes swirling around the ex-president.” 17

Even the website Torrent Freak wondered:

“In an ideal world, the failure of Trump’s motion to dismiss in September 2021 should’ve been seen as an opportunity to settle the case privately.

A very small slice of humble pie and some tea, perhaps, so that everyone could move on. Or even negotiating the terms of the settlement Grant offered in August 2020 before filing the lawsuit.” 18

And as a high-profile individual that once published a book under his name about “The Art of the Deal,” Trump should have known that “The Art of No Deal” can be much costlier.

Notes:

- Grant v. Trump 2024 WL 4179057 SDNY 2024 (citations are to the WestLaw pagination) ↩

- “Electric Avenue” Derails Trump Train ↩

- Donald Trump Loses ‘Electric Avenue’ Legal Battle With Eddy Grant; Jury Could Be Convened Over Compensation From Ex-POTUS – Update ↩

- Donald Trump loses legal fight over using Eddy Grant song without permission ↩

- Id. ↩

- “Electric Avenue” Derails Trump Train ↩

- “Electric Avenue” Derails Trump Train ↩

- Wikipedia – Eddy Grant ↩

- Are Foreign Creators Protected in the US? ↩

- Grant v. Trump at 1 ↩

- Id. at 2 ↩

- Id. ↩

- Grant v. Trump at 2 ↩

- Grant v. Trump at 3 ↩

- Grant v. Trump at 5 ↩

- Trump Claims “Absolute Immunity” in Eddy Grant Copyright Suit ↩

- Id. ↩

- Eddy Grant Wins: Trump’s ‘Fair Use’ of ‘Electric Avenue’ Was Anything But ↩

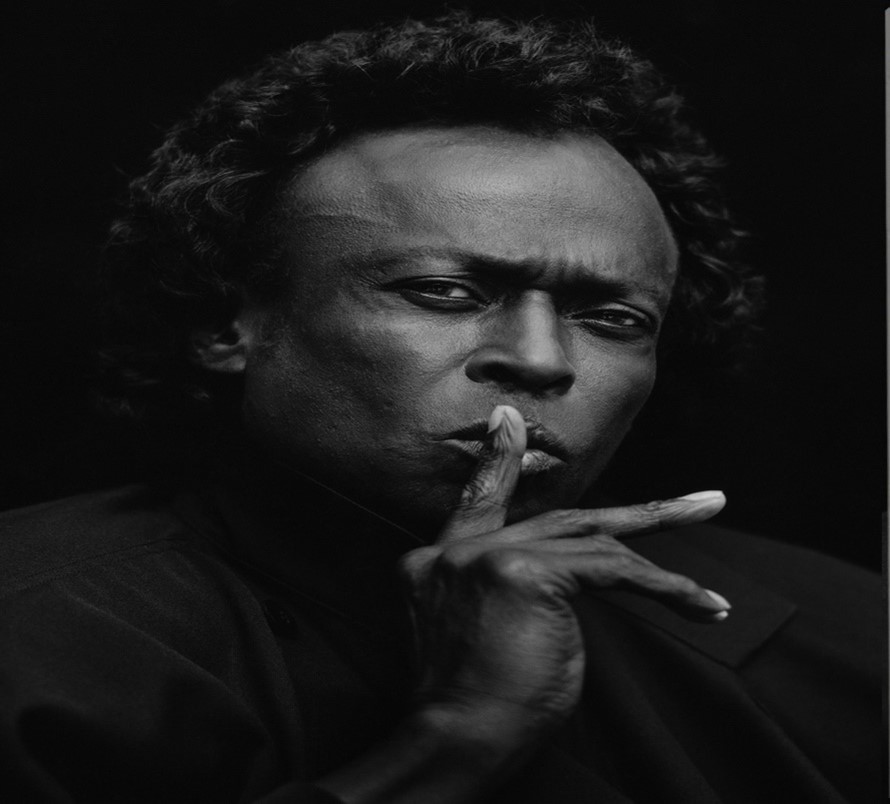

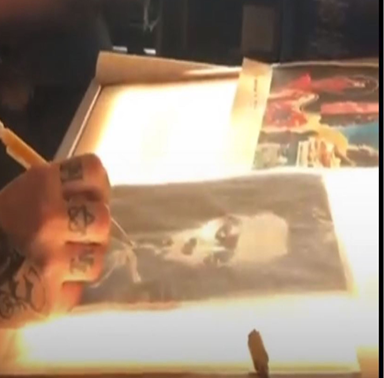

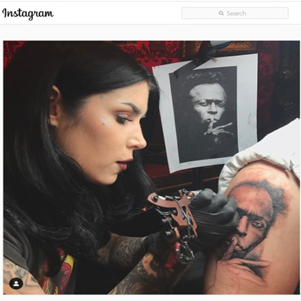

Here is a side-by-side comparison of the photograph and finalized tattoo:

Here is a side-by-side comparison of the photograph and finalized tattoo: