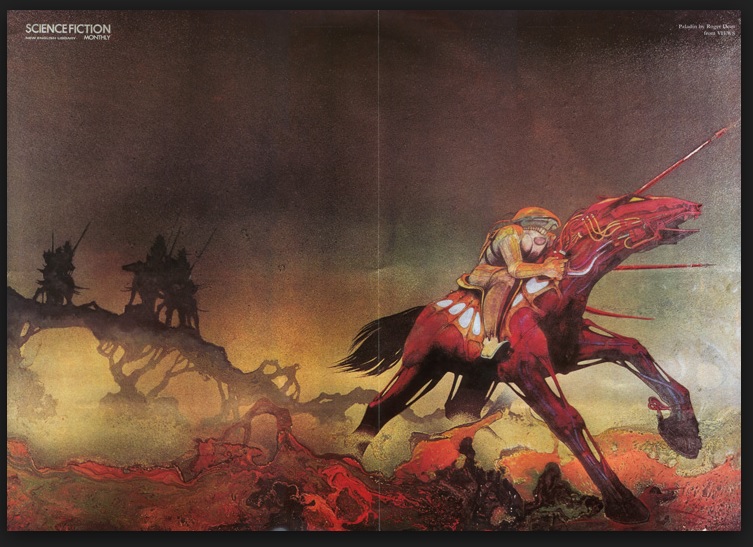

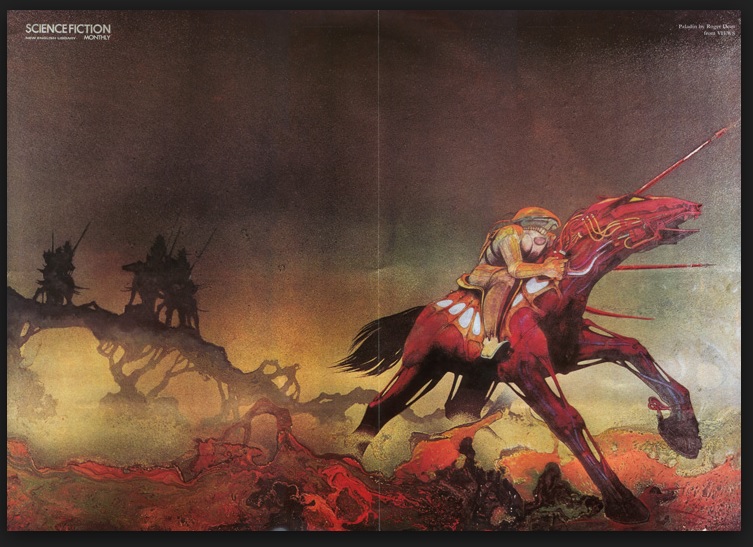

On September 17, 2014, Judge Jesse Furman dismissed world renowned artist Roger Dean's lawsuit against James Cameron and the motion picture Avatar.[ref]Dean v. Cameron, 2014 WL 4638355, Southern District of New York, 2014[/ref] If the name Roger Dean does not strike an immediate chord, be assured you have doubtlessly seen his work. He is best known for designing album covers and artwork for the band Yes, including the albums "Fragile," "Close to the Edge," "Relayer" and "Keys to Ascension."[ref]Roger Dean (artist)[/ref] He has also designed album covers for Uriah Heep, Asia, and Gentle Giant.[ref]Id.[/ref] Dean had alleged that the movie had copied elements from 14 of his paintings.

These allegations were nothing new. Immediately upon the release of Avatar, numerous commentators noticed the similarity between Dean's work and the depiction of the planet Pandora in Avatar.[ref]Avatar Sparks New Interest In The Strange Visions That Inspired It[/ref] So obvious was the connection that Cameron was directly asked about it in an interview with Entertainment Weekly.[ref]'Avatar': Your Questions Answered[/ref]

"Where did Cameron get the idea for the floating mountains? Was that from a Yes album cover?

‘It might have been,' the director says with a laugh. ‘Back in my pot-smoking days.'"[ref]Id.[/ref]

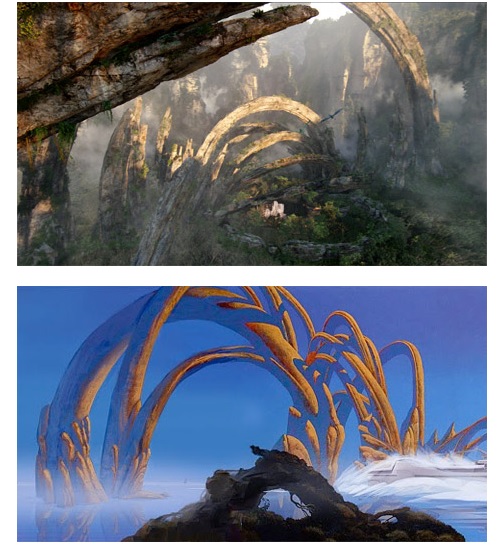

I had very much the same experience when I watched Avatar. In particular, this scene immediately reminded me of Dean's cover to Yes' "Keys to Ascension." The Avatar scene is on top. Dean's art is on the bottom.

Before we enter into a full-fledged analysis of the Judge's decision, I must give the following cognitive bias alert: I am a huge fan of both the band Yes and Roger Dean's work. I have two of his books. So feel free to view my analysis through that prism.

In my mind, the issue here is a test for infringement called "total concept and feel." The Second Circuit, which governs the District Court here, appears to be the originator of this test.[ref]Reyher v. Children's Television Workshop, 533 F.2d, Second Circuit Court of Appeals 1976[/ref] "Total concept and feel" arises because a "defendant may infringe on the plaintiff's work not only through literal copying of a portion of it, but also by parroting properties that are apparent only when numerous aesthetic decisions embodied in the plaintiff's work of art...are considered in relation to one another."[ref]Tufenkian Import/Export Venture v. Einstein Moomjy, 338 F.3d 127, at 134,Second Circuit Court of Appeals 2003[/ref] The Court here, makes a passing reference to the test of total concept and feel, but engages in absolutely no discussion of its elements or how they might apply to this case. This is a serious error in my opinion.

Instead, the Court hamstrings Dean's case by insisting that only the individual paintings standing alone can be compared to Avatar and not Dean's body of work, stating "[n]othing in the Copyright Act or Second Circuit case law supports the view that a plaintiff's entire oeuvre, or even an aggregated portion of it, may be used as the point of comparison where the works included therein bear little or no relation to one another beyond ‘style.'"[ref]Dean at page 7 (citations are made to the original pagination of the opinion)[/ref] To say that a principle lacks support is not the same thing as saying the position is untenable. In fact, a District Court in California allowed the aggregation of elements from the (at the time) 16 James Bond films.[ref]Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc. v. American Honda Motor Co. 900 F.Supp1287, District Court for the Central District of California 1995[/ref] There, in granting the Plaintiff's motion for preliminary injunction, the Court specifically referenced elements from 5 different James Bond films.[ref]Id. at 1298[/ref]

Next, the Court in Dean cites to the authority that "the underlying issue [is] whether a lay observer would consider the works as a whole substantially similar to one another."[ref]Dean at page 7 [/ref] Then two pages later, in a complete about face, states that the numerous examples of persons commenting on the similarities between Dean's work and Avatar are irrelevant. "It is well established, however, that the opinions of third parties—even experts—are irrelevant to a determination of substantial similarity."[ref]Dean at page 9[/ref] And yet, four pages later, the Court reverses itself again and pats itself on the back in that "the Court confidently conclude[s] that no average lay observer would recognize Avatar as having been appropriated from the copyrighted work,"[ref]Dean at page 13[/ref] despite the numerous examples to the contrary. If you are unsure on this point, do a search for "Roger Dean and Avatar" and take a look at the results.

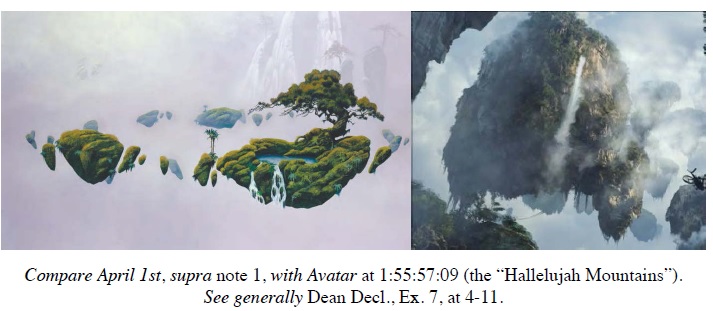

The final nail in the coffin for Dean's case appears to be the Court's belief that since Dean's work is a painting and therefore static, and Avatar's is a motion picture, and therefore fluid, one cannot be substantially similar to the other.[ref]Dean at 11[/ref] "[T]he fact that the "Hallelujah Mountains" appear in ‘a wholly dissimilar and dynamic medium, in which camera angles, lighting, and focus are changing' rapidly, [citation omitted] no reasonable jury could find that Defendants' and Plaintiffs' works are substantially similar."[ref]Id.[/ref] The Court then cites generally to a case, Warner Bros. v. American Broadcasting Cos.,[ref]720 F.2d 231, Second Circuit Court of Appeals 1983[/ref] which does not really support the proposition for which it is being cited.

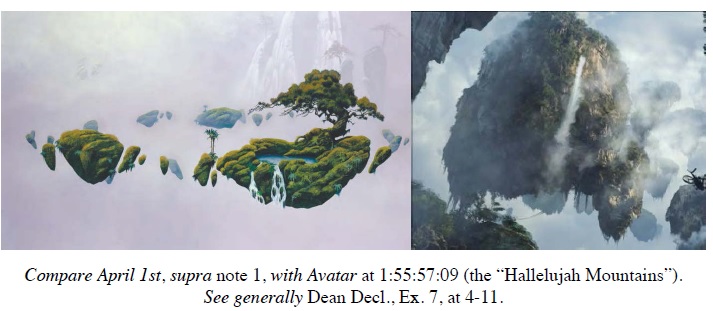

Let's go back to the fact that Cameron is admittedly familiar with Dean's work. Therefore, the question of access can be presumed, and in fact the Court agrees with this presumption.[ref]Dean at 7[/ref] Yet, remember, this is not summary judgment; this is a motion to dismiss. The judge has allowed no discovery at this point. No depositions have been taken of any of the persons who did the design work on Avatar. So, in the Court's own words "[t]o survive the motion, the complaint must "state a claim to relief that is plausible on its face."[ref]Dean at 5[/ref] So, we have access, plus the similarities which are plainly obvious to many people. The following are side to side comparisons provided by the Court in an appendix to the opinion.

Dean's image is on the left. Avatar's is on the right. The Court makes much of the fact that Avatar's floating boulders are covered with vegetation, while Dean's are bare.[ref]Dean at 11[/ref] However, beyond that, the composition of the two has several similarities: 1) the floating boulders 2) the line of boulders starts out heading right, then veers left 3) a tall tree at the midpoint of the frame and 4) another large floating mass appears in the upper left quadrant. This seems to suggest that Dean's work was copied and then altered, which would make it a derivative work, and which would have required Dean's permission.

Dean's image is on the left. Avatar's is on the right. The Court makes much of the fact that Avatar's floating boulders are covered with vegetation, while Dean's are bare.[ref]Dean at 11[/ref] However, beyond that, the composition of the two has several similarities: 1) the floating boulders 2) the line of boulders starts out heading right, then veers left 3) a tall tree at the midpoint of the frame and 4) another large floating mass appears in the upper left quadrant. This seems to suggest that Dean's work was copied and then altered, which would make it a derivative work, and which would have required Dean's permission.

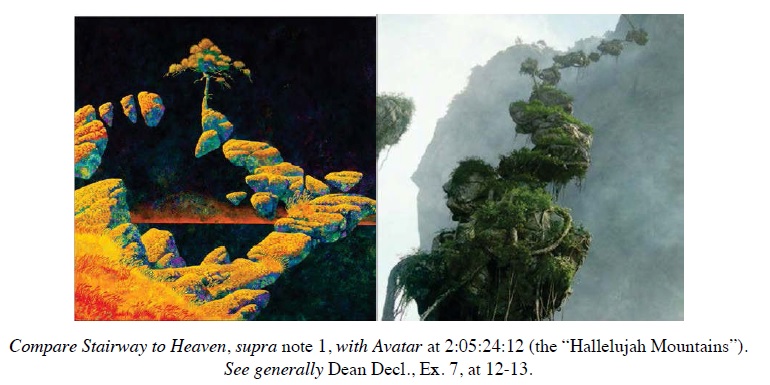

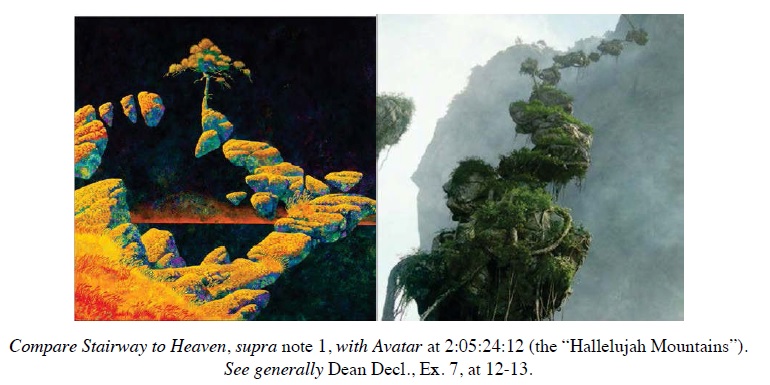

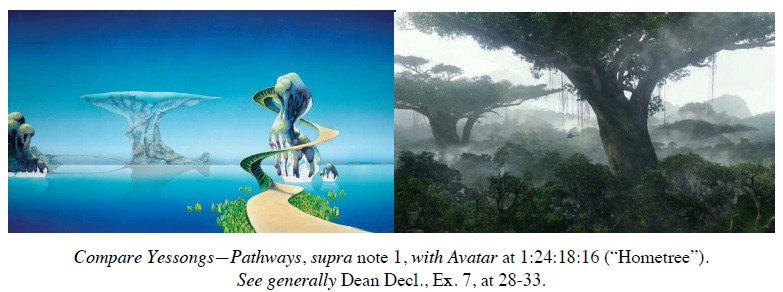

Dean's image is on the left. Avatar's is on the right. This painting is very famous and was part of the multi-gatefold album "Yessongs."Agreed that one is a mountain and one is a tree. But the shape of the tree and that of the mountain almost duplicate each other, right down to the size and shape of the gap in the structure midway right of the shaft. Also, look at the placement of the images within the frame.

Also, there is this. Dean's painting…

Dean's image is on the left. Avatar's is on the right. This painting is very famous and was part of the multi-gatefold album "Yessongs."Agreed that one is a mountain and one is a tree. But the shape of the tree and that of the mountain almost duplicate each other, right down to the size and shape of the gap in the structure midway right of the shaft. Also, look at the placement of the images within the frame.

Also, there is this. Dean's painting…

And the corresponding image from Avatar.

And the corresponding image from Avatar.

After a while, the coincidences begin to pile up. These "coincidences" all point to the same source: Roger Dean. So, I think at this stage of the pleadings that Roger Dean has at least stated a "plausible claim" that his work has been copied, with varying degrees of similarity, by those responsible for the art direction of Avatar. Certainly, he has stated a plausible claim that the "total concept and feel" of his work has been appropriated "by parroting properties that are apparent only when numerous aesthetic decisions embodied in the plaintiff's work of art...are considered in relation to one another."[ref]See note 8, supra[/ref] The Court tacitly admits as much when it states "the commentators cited by Plaintiff may well be correct that Defendants—wittingly or unwittingly—took some inspiration from Plaintiff, or even copied elements of his works in making their film."[ref]Dean at 13[/ref] This is the precise reason why the standard of "total concept and feel" is so important to this case, a standard which was virtually ignored by the Court, save for one passing reference.

It would have been better to have the suit go forward. The discovery would then center on the persons responsible for creating these images. Precisely where and how did they come up with ideas and resulting visual images that wound up on screen? Perhaps we can then learn what the true source of the images is.

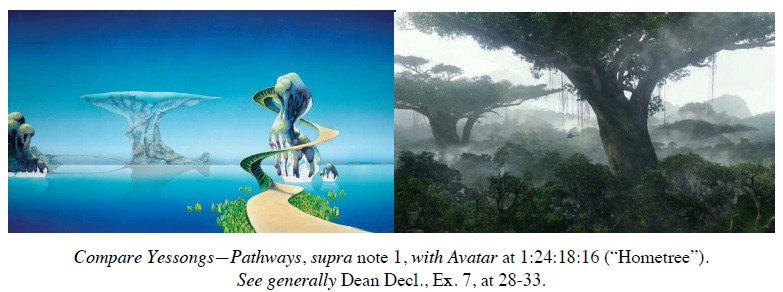

The Court trots out the old trope that "[t]he copyright laws do not protect styles," but it is apparent that Dean's work is more than a "style." His subject matter is indeed "otherworldly" in that it depicts familiar objects such as trees and mountains, but in shapes and settings and with certain properties which are unknown on planet Earth. One such example is not only the floating land mass, but a source-less waterfall contained within that floating land mass, as seen here. Dean's image is on the left. Avatar's is on the right.

After a while, the coincidences begin to pile up. These "coincidences" all point to the same source: Roger Dean. So, I think at this stage of the pleadings that Roger Dean has at least stated a "plausible claim" that his work has been copied, with varying degrees of similarity, by those responsible for the art direction of Avatar. Certainly, he has stated a plausible claim that the "total concept and feel" of his work has been appropriated "by parroting properties that are apparent only when numerous aesthetic decisions embodied in the plaintiff's work of art...are considered in relation to one another."[ref]See note 8, supra[/ref] The Court tacitly admits as much when it states "the commentators cited by Plaintiff may well be correct that Defendants—wittingly or unwittingly—took some inspiration from Plaintiff, or even copied elements of his works in making their film."[ref]Dean at 13[/ref] This is the precise reason why the standard of "total concept and feel" is so important to this case, a standard which was virtually ignored by the Court, save for one passing reference.

It would have been better to have the suit go forward. The discovery would then center on the persons responsible for creating these images. Precisely where and how did they come up with ideas and resulting visual images that wound up on screen? Perhaps we can then learn what the true source of the images is.

The Court trots out the old trope that "[t]he copyright laws do not protect styles," but it is apparent that Dean's work is more than a "style." His subject matter is indeed "otherworldly" in that it depicts familiar objects such as trees and mountains, but in shapes and settings and with certain properties which are unknown on planet Earth. One such example is not only the floating land mass, but a source-less waterfall contained within that floating land mass, as seen here. Dean's image is on the left. Avatar's is on the right.

All in all, there is far too much smoke to totally discount the existence of a fire, especially at the Motion to Dismiss stage of the case. As for the "court of public…opinion"[ref]Dean at 14[/ref] referred to by the Court, they have already weighed in and found the Defendant guilty.

As one commentator put it, "[t]here is some convincing evidence of borrowing, shown here in the photos above and below and this has been discussed exhaustedly in forums online. Whether the might of the teams of lawyers representing Cameron and Fox will win, remains to be seen.[sic] We feel it would be sensible for Cameron to admit to being inspired by Mr. Dean's work, give him a title credit and a few million and bury it."[ref]Artist Roger Dean Sues Avatar Director James Cameron Over Plagiarism[/ref]

All in all, there is far too much smoke to totally discount the existence of a fire, especially at the Motion to Dismiss stage of the case. As for the "court of public…opinion"[ref]Dean at 14[/ref] referred to by the Court, they have already weighed in and found the Defendant guilty.

As one commentator put it, "[t]here is some convincing evidence of borrowing, shown here in the photos above and below and this has been discussed exhaustedly in forums online. Whether the might of the teams of lawyers representing Cameron and Fox will win, remains to be seen.[sic] We feel it would be sensible for Cameron to admit to being inspired by Mr. Dean's work, give him a title credit and a few million and bury it."[ref]Artist Roger Dean Sues Avatar Director James Cameron Over Plagiarism[/ref]

Dean's image is on the left. Avatar's is on the right. The Court makes much of the fact that Avatar's floating boulders are covered with vegetation, while Dean's are bare.[ref]Dean at 11[/ref] However, beyond that, the composition of the two has several similarities: 1) the floating boulders 2) the line of boulders starts out heading right, then veers left 3) a tall tree at the midpoint of the frame and 4) another large floating mass appears in the upper left quadrant. This seems to suggest that Dean's work was copied and then altered, which would make it a derivative work, and which would have required Dean's permission.

Dean's image is on the left. Avatar's is on the right. The Court makes much of the fact that Avatar's floating boulders are covered with vegetation, while Dean's are bare.[ref]Dean at 11[/ref] However, beyond that, the composition of the two has several similarities: 1) the floating boulders 2) the line of boulders starts out heading right, then veers left 3) a tall tree at the midpoint of the frame and 4) another large floating mass appears in the upper left quadrant. This seems to suggest that Dean's work was copied and then altered, which would make it a derivative work, and which would have required Dean's permission.

Dean's image is on the left. Avatar's is on the right. This painting is very famous and was part of the multi-gatefold album "Yessongs."Agreed that one is a mountain and one is a tree. But the shape of the tree and that of the mountain almost duplicate each other, right down to the size and shape of the gap in the structure midway right of the shaft. Also, look at the placement of the images within the frame.

Also, there is this. Dean's painting…

Dean's image is on the left. Avatar's is on the right. This painting is very famous and was part of the multi-gatefold album "Yessongs."Agreed that one is a mountain and one is a tree. But the shape of the tree and that of the mountain almost duplicate each other, right down to the size and shape of the gap in the structure midway right of the shaft. Also, look at the placement of the images within the frame.

Also, there is this. Dean's painting…

And the corresponding image from Avatar.

And the corresponding image from Avatar.

After a while, the coincidences begin to pile up. These "coincidences" all point to the same source: Roger Dean. So, I think at this stage of the pleadings that Roger Dean has at least stated a "plausible claim" that his work has been copied, with varying degrees of similarity, by those responsible for the art direction of Avatar. Certainly, he has stated a plausible claim that the "total concept and feel" of his work has been appropriated "by parroting properties that are apparent only when numerous aesthetic decisions embodied in the plaintiff's work of art...are considered in relation to one another."[ref]See note 8, supra[/ref] The Court tacitly admits as much when it states "the commentators cited by Plaintiff may well be correct that Defendants—wittingly or unwittingly—took some inspiration from Plaintiff, or even copied elements of his works in making their film."[ref]Dean at 13[/ref] This is the precise reason why the standard of "total concept and feel" is so important to this case, a standard which was virtually ignored by the Court, save for one passing reference.

It would have been better to have the suit go forward. The discovery would then center on the persons responsible for creating these images. Precisely where and how did they come up with ideas and resulting visual images that wound up on screen? Perhaps we can then learn what the true source of the images is.

The Court trots out the old trope that "[t]he copyright laws do not protect styles," but it is apparent that Dean's work is more than a "style." His subject matter is indeed "otherworldly" in that it depicts familiar objects such as trees and mountains, but in shapes and settings and with certain properties which are unknown on planet Earth. One such example is not only the floating land mass, but a source-less waterfall contained within that floating land mass, as seen here. Dean's image is on the left. Avatar's is on the right.

After a while, the coincidences begin to pile up. These "coincidences" all point to the same source: Roger Dean. So, I think at this stage of the pleadings that Roger Dean has at least stated a "plausible claim" that his work has been copied, with varying degrees of similarity, by those responsible for the art direction of Avatar. Certainly, he has stated a plausible claim that the "total concept and feel" of his work has been appropriated "by parroting properties that are apparent only when numerous aesthetic decisions embodied in the plaintiff's work of art...are considered in relation to one another."[ref]See note 8, supra[/ref] The Court tacitly admits as much when it states "the commentators cited by Plaintiff may well be correct that Defendants—wittingly or unwittingly—took some inspiration from Plaintiff, or even copied elements of his works in making their film."[ref]Dean at 13[/ref] This is the precise reason why the standard of "total concept and feel" is so important to this case, a standard which was virtually ignored by the Court, save for one passing reference.

It would have been better to have the suit go forward. The discovery would then center on the persons responsible for creating these images. Precisely where and how did they come up with ideas and resulting visual images that wound up on screen? Perhaps we can then learn what the true source of the images is.

The Court trots out the old trope that "[t]he copyright laws do not protect styles," but it is apparent that Dean's work is more than a "style." His subject matter is indeed "otherworldly" in that it depicts familiar objects such as trees and mountains, but in shapes and settings and with certain properties which are unknown on planet Earth. One such example is not only the floating land mass, but a source-less waterfall contained within that floating land mass, as seen here. Dean's image is on the left. Avatar's is on the right.

All in all, there is far too much smoke to totally discount the existence of a fire, especially at the Motion to Dismiss stage of the case. As for the "court of public…opinion"[ref]Dean at 14[/ref] referred to by the Court, they have already weighed in and found the Defendant guilty.

As one commentator put it, "[t]here is some convincing evidence of borrowing, shown here in the photos above and below and this has been discussed exhaustedly in forums online. Whether the might of the teams of lawyers representing Cameron and Fox will win, remains to be seen.[sic] We feel it would be sensible for Cameron to admit to being inspired by Mr. Dean's work, give him a title credit and a few million and bury it."[ref]Artist Roger Dean Sues Avatar Director James Cameron Over Plagiarism[/ref]

All in all, there is far too much smoke to totally discount the existence of a fire, especially at the Motion to Dismiss stage of the case. As for the "court of public…opinion"[ref]Dean at 14[/ref] referred to by the Court, they have already weighed in and found the Defendant guilty.

As one commentator put it, "[t]here is some convincing evidence of borrowing, shown here in the photos above and below and this has been discussed exhaustedly in forums online. Whether the might of the teams of lawyers representing Cameron and Fox will win, remains to be seen.[sic] We feel it would be sensible for Cameron to admit to being inspired by Mr. Dean's work, give him a title credit and a few million and bury it."[ref]Artist Roger Dean Sues Avatar Director James Cameron Over Plagiarism[/ref]