That strange thumping sound you heard last Monday was the sound of the top executives of Sirius XM Radio and Pandora falling over in a dead faint. On September 22, 2014, a federal Judge granted Flo and Eddie Inc.'s Motion for Summary Judgment, ruling that under California law, Sirius XM had to pay to digitally broadcast pre-1972 sound recordings.[ref]

Flo & Eddie, Inc. v. Sirius XM Radio, Inc., 2014 WL 4725382 Central District of California 2014[/ref] Since this was filed as a class action, this meant that Sirius would owe damages not only to Flo and Eddie, Inc., but potentially all other owners of pre-1972 sound recordings. This class of recordings includes

every recording ever made by The Beatles, The Doors, Jimi Hendrix, and Janis Joplin, not to mention Glen Miller and Tommy Dorsey. Sirius XM dedicates entire channels to these recordings. Sirius XM channels 4, 5, & 6 exclusively play recordings from the 40's, 50's and 60's respectively.[ref]

Sirius XM Satellite Radio Channel Lineup[/ref] Throw in the fact that these channels operate 24 hours and day, seven days a week, and that Sirius has never paid any royalties to broadcast these songs, damages in the multiple millions of dollars is a forgone conclusion. "According to estimates, 10-15 percent of all songs Sirius transmits are pre-72s which would amount to about $2.72 to $4.08 million in royalty payments per year."[ref]Gill, Leigh F., Liberman, Heather R., Stein, Gregory S.,

Time to Face the Music: Current State and Federal Copyright Issues With Pre-1972 Sound Recordings, Landslide Volume 6, Number 6 July/August 2014 at page 3[/ref] Sirius XM's internet counterpart, Pandora, likewise pays nothing to owners of these recordings when it streams them.[ref]

You See What Happens When You Find a Stranger in the Alps? Sirius Screws It Up For All Broadcasters.[/ref] The implications of this ruling are huge. To paraphrase David Byrne of the

Talking Heads, "Well, how did we get here?" The answer, as usual, is fairly complicated.

In the early days of recorded music, the only way to obtain a copy of a record was to buy a vinyl record from the record store. The pressing of a vinyl record required equipment far beyond the reach of the average consumer, so the record companies enjoyed almost total control over the distribution of their product. Then came the audio cassette. For the first time, a consumer could make a copy of a recording in their home at an inexpensive price. It wasn't long before someone figured out that selling bootlegged cassette copies could be a profitable business, and the first wave of record piracy began. The record companies found themselves without a viable legal remedy. No copyright protection existed for the recording, only for the songs contained on the recording. Some of the bootleggers went "legit," obtaining licenses for the songs from clearing houses such as the Harry Fox Agency, paying the few pennies per copy they required, and

voilà: a "legitimate" product that did not violate the copyright laws. I remember seeing these in my local record store. Cassettes of albums by major artists, such as

Cream and

Credence Clearwater Revival appeared in the bins, yet all of them had the same cover art. The only thing that varied was the name of the artists and the songs on the cassette.

In response, State laws sprung up, but proved unsatisfactory as, quite predictably, protection was not universal and the level and effectiveness of the protection varied widely. The ultimate remedy was to create a new class of copyright protected work: the sound recording. Effective February 15, 1972, Congress declared that recordings created after that date had the full might of the copyright act behind them.

About this same time, the 60's rock band

The Turtles were calling it quits. They had several hits, including, "It Ain't Me Babe," "Eleanor," "She'd Rather Be With Me" and "Happy Together," but their label was having serious financial problems,[ref]

White Whale Records[/ref] and the band suspected they were not getting paid their royalties. Two of the members, Mark Volman and Howard Kaylan, later acquired the rights to the master tapes as a settlement with their former label for underpayment of royalties.[ref]

Plaintiff Flo & Eddie, Inc's Reply to Sirius XM Radios Motion for Summary Judgment, Case number 13-CV-23182 US District Court for the Southern District of Florida at page 3. (NB: If the link does not work, try a cut and paste of the web address into your browser.)

http://assets.law360news.com/0568000/568058//mnt/rails_cache/https-ecf-flsd-uscourts-gov-doc1-051113970062.pdf[/ref] They bought out the interests of the other members of

The Turtles[ref]

Id.[/ref] and formed Flo & Eddie, Inc. in California in 1971.[ref]

Id.[/ref] The newly formed corporation, (named after the stage names they were using with Frank Zappa [ref]

Flo & Eddie[/ref]) was then transferred the ownership of the master tapes.[ref]

Plaintiff Flo & Eddie, Inc's Reply to Sirius XM Radios Motion for Summary Judgment, Case number 13-CV-23182 US District Court for the Southern District of Florida at page 3.[/ref] They may have been hippies, but this was a very shrewd business move.

Meanwhile, back in the halls of Congress, the newly minted sound recordings lacked one major right, the right of public performance.[ref]17 USC 106 (4)[/ref] This was due to the lobbying might of the broadcasters, who insisted then, and continue to insist to this day, that their playing of music is equivalent of millions of dollars of free advertising to record companies,[ref]

See, e.g. James N. Dertouzos, Ph.D.

Radio Airplay and the Record Industry: An Economic Analysis preparedFor the National Association of Broadcasters June 2008:

https://www.nab.org/documents/resources/061008_Dertouzos_Ptax.pdf [/ref]and thus should not be compensated. So for the next 24 years, this was the law of the land, until the invention of digital recording and the internet.

In 1995, understanding that the performance of a sound recording by a digital transmission had the potential to create a digital copy of that same sound recording, Congress enacted the Digital Performing Rights Act (DPRA). It created, commencing July 1, 1996, three tiers: 1) digital broadcasts, which were exempted, 2) subscription but non-demand services, which were granted a blanket license and 3) subscription on demand services, which would require a fully negotiated license similar to a mechanical license.[ref]17 USC 114-115[/ref] Sirius XM and Pandora are level 2 services. Spotify and Rhapsody are level 3 services.

In 2011, Sirius XM unilaterally stopped accounting for pre-72 in the accounting made to SoundExchange, the unified collection agency for digital transmission royalties.[ref]Gill, Liberman and Stein at page 3[/ref] SoundExchange responded by filing suit.[ref]

Id.[/ref]

For their part, Flo & Eddie, Inc. have filed three lawsuits against Sirius XM, in California, New York and oddly enough, Florida.[ref]

Flo & Eddie, Inc, v. Sirius XM Radio, Inc. Case no.1:13-CV-23182 US District Court for the Southern District of Florida, Miami Division

http://assets.law360news.com/0470000/470617/Turtles%20v%20Sirius.pdf [/ref] California is the home to Flo & Eddie, Inc., and New York is the corporate home of Sirius XM, which is a Delaware Corporation.[ref]

Id. at page 4.[/ref] The only nexus Florida has to the litigants is that obviously Sirius XM broadcasts into the Florida market, and according to the complaint, has offices in Miami, Jupiter, Deerfield Beach and Boca Raton.[ref]

Id.[/ref] Thus, Flo & Eddie have filed suit in three out of the four most populated states.[ref]

List of U.S. states and territories by population[/ref] Why they have not filed suit in Texas is currently unknown.

Florida has a law directly on point, 540.011.[ref]

The 2014 Florida Statutes[/ref] It provides, in part, that "It is unlawful [k]nowingly and willfully and without the consent of the owner, to transfer or cause to be transferred, directly or indirectly, any sounds recorded on a phonograph record… with the intent to…use or cause to be used for profit through public performance, such article on which sounds are so transferred without consent of the owner." It seems that this law would directly apply, since Sirius XM has made an unauthorized copy of

The Turtles for the purposes of profit by public performance. Yet Flo & Eddie have not invoked this statute, instead suing for common law copyright infringement, unfair competition, conversion and civil theft.[ref]

Flo & Eddie, Inc, v. Sirius XM Radio, Inc. Case no.1:13-CV-23182 at page 9.[/ref] Perhaps this is because the statute itself states that "[t]his section shall neither enlarge nor diminish the right of parties in private litigation." The statute itself is mentioned but once in the court documents, and only for the proposition that Florida law recognizes the rights of pre-1972 sound recording owners.[ref]

Plaintiff Flo & Eddie, Inc's Response to Sirius XM radio's Motion for Summary Judgment at 7

http://assets.law360news.com/0568000/568058//mnt/rails_cache/https-ecf-flsd-uscourts-gov-doc1-051113970062.pdf Again, If the link does not work, try a cut and paste of the web address into your browser[/ref] It is also worth noting that Flo & Eddie's claim for civil theft under Florida law carries with it the potential for an award of triple the amount of proven damages.[ref]

The 2014 Florida Statutes[/ref]

Sirius XM has filed for summary judgment in the Florida action.[ref]

Defendant Sirius XM's Motion for Summary Judgment on Liability and Supporting Memorandum of Law[/ref] Flo & Eddie have filed a response,[ref]

Plaintiff Flo & Eddie, Inc.'s Response to Sirius XM Radio's Motion for Summary Judgment[/ref] but have not yet moved for summary judgment on its own behalf.

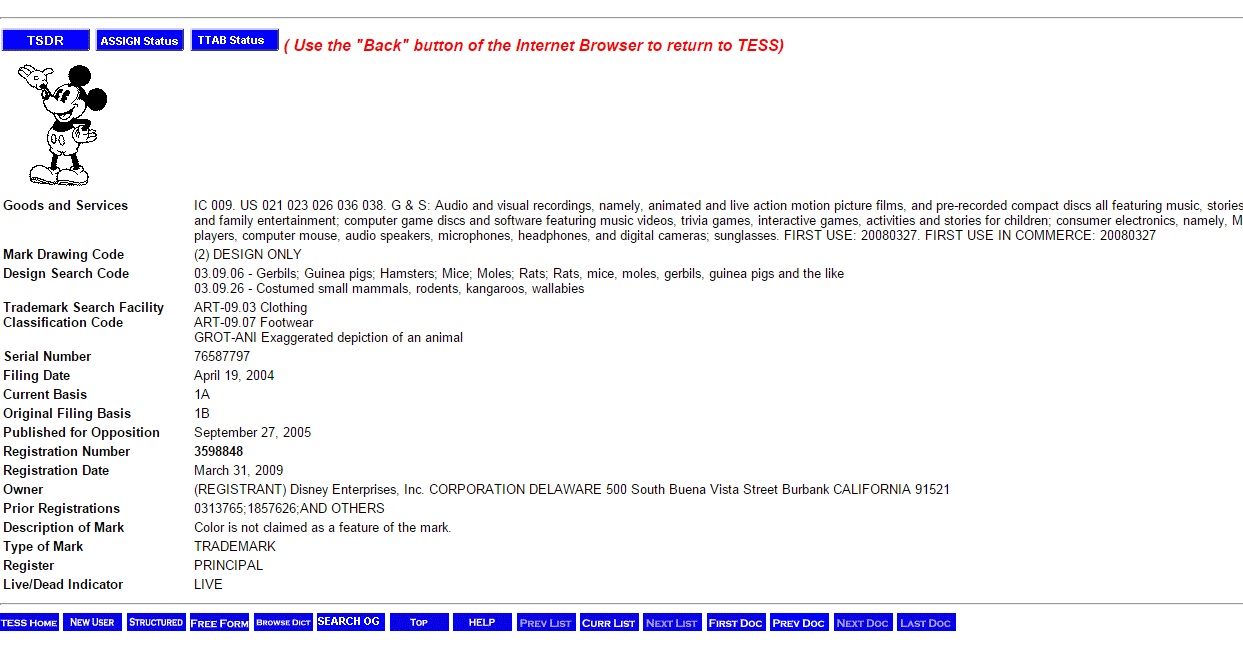

Sirius XM first advances the argument that since Congress has never granted pre-1972 sound recording performance rights, no right exists at all.[ref]

Defendant Sirius XM's Motion for Summary Judgment on Liability and Supporting memorandum of Law at 5-7[/ref] This argument is rather curious because under the copyright act, pre-1972 recordings are explicitly removed from the purview of the statute. "With respect to sound recordings fixed before February 15, 1972, any rights or remedies under the common law or statutes of any State shall not be annulled or limited by this title until February 15, 2067."[ref]17 USC 301 (c)[/ref] So, not only did Congress recognize the continuing protection of State copyright protection for sound recordings, but it explicitly stated that nothing in the Act "annulled or limited" any State law, other than providing for a terminal date of 95 years from the first granting of sound recording rights, so that pre-1972 sound recordings would not enjoy perpetual protection under the law of any State. So how can the failure of Congress to act proceed to annul a State law providing for sound recording protection for public performances? This would not have been my first argument.

Next up, without actually mentioning the words "public domain," Sirius advances the argument that all pre-1972 sound recordings are in the public domain, presumably because of publication without copyright notice.[ref]

Defendant Sirius XM's Motion for Summary Judgment on Liability and Supporting memorandum of Law at 8-9[/ref] The failure to mention the words "public domain" is gleefully pounced upon by Flo & Eddie in their response, quoting verbatim deposition testimony from Sirius XM Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer, David J. Frear: [ref]

Sirius XM Management Bios - David J. Frear[/ref]

Q: Is it Sirius XM's position the pre-1972 sound recordings are in the public domain?

A: Yes.[ref]

Plaintiff Flo & Eddie, Inc's Response to Sirius XM radio's Motion for Summary Judgment at 2[/ref]

Later there was this response:

"To my knowledge we've never entered into discussions with

The Turtles with respect to their songs. That-my understanding is that they're in the public domain and so we are simply using them under that theory."[ref]

Id.[/ref]

Under the then current edition of the copyright act in 1972, it was true that publishing your work without copyright notice would inject your work into the public domain. The problem with this argument is that sound recordings did not fall within the "subject matter" of copyright before 1972, when the right was first granted. Not being within the subject matter meant that Federal copyright law absolutely did not apply to pre-1972 sound recordings at all, so the rule against publishing without copyright notice does not apply. A Federal Judge from the Middle District of Florida agrees on this point.[ref]

CBS, Inc. v. Garrod, 622 F.Supp 532 US District Court for the Middle District of Florida 1985[/ref] Again, a very curious argument.

Sirius XM's final major argument is that State regulation of what is in effect a national broadcast operation would interfere with interstate commerce, and only Congress has the power to control interstate commerce. Any detailed discussion of the Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution would induce sleep and is much better suited to a law school classroom. In short, Sirius XM made this same argument in the California action, and the Judge was so unimpressed with the argument that he dismissed it in a footnote, citing controlling U.S. Supreme Court case law.[ref]

Flo & Eddie, Inc. v. Sirius XM Radio, Inc., 2014 WL 4725382 at page 10[/ref]

The difference between the California and the Florida action is that California had an actual statute in place, where the Florida action is based upon the "common law." The "common law" is a series of legal principles established through case decisions rendered over time and are not generated by the State Legislature.

The case of

CBS v. Garrod held that Florida does recognize common law copyright.[ref]622 F.Supp 532 US District Court for the Middle District of Florida 1985[/ref] The problem is that the case does not deal with the issue of whether common law copyright extended to performances of sound recordings, since the case dealt with the piracy of physical copies. Flo & Eddie, as Plaintiffs, bear the burden of proof to show that Florida common law copyright extends to such performances. There is no such proof, but only because it does not appear that any Florida Court has ever considered the question. What we may see is that the issue is referred to the Florida Supreme Court for resolution.

So what happens next? Surely Sirius XM is not simply going to stop broadcasting channels 4, 5, & 6 into California, even if that were technologically possible. Alternatively, is a broadcaster that can play absolutely NO

Beatles songs a very attractive option? Further, what might the damages be, and what might the royalty be going forward? Sirius XM certainly knows how many subscribers it has in California, but since this is California law, not Federal law, Flo & Eddie (and the members of the class, if and when it is established) are not bound by the royalty rate set by the CRB in establishing the blanket license rates. They could demand any sum of money going forward. How much is it worth to Sirius XM to be able to play

The Beatles,

The Doors and Jimi Hendrix?

The implications get bigger when you consider YouTube. Here are

The Turtles performing "Happy Together" on YouTube.[ref]

The Turtles - Happy Together - 1967[/ref] The lead vocals are live, but everything else is mimed to the original sound recording. If YouTube is not currently paying Flo & Eddie for this performance, then they're going to have to start. The bigger question is, does the DMCA "safe harbor" provisions apply to pre-1972 sound recordings? The New York state appeals court has ruled that it does not.[ref]

UMG Recordings, Inc. v. Escape media Group, Inc. 964 N.Y.S. 106 New York Appellate Division 2013:

http://www.documentcloud.org/documents/691437-umg-recordings-inc-v-escape-media-group-inc.html [/ref] A New York Federal Court says that it does.[ref]

Capitol Records, Inc. v. MP3tunes, LLC, 821 F.Supp 2d 627 District Court for the Southern District of New York 2011[/ref] That ruling is currently under a special appeal to the Second Circuit to resolve the question.[ref]Gill, Leigh F., Liberman, Heather R., Stein, Gregory S.,

Time to Face the Music: Current State and Federal Copyright Issues With Pre-1972 Sound Recordings, Landslide Volume 6, Number 6 July/August 2014 at page 3[/ref] If the answer to the question is "no" then YouTube has committed copyright infringement every time the video containing a pre-1972 sound recording has been streamed.

Currently before Congress is the RESPECT Act, which would provide for performance royalties for pre-1972 sound recordings.[ref]

Id. at 4[/ref] However, this legislation would not "federalize" pre-1972 sound recordings, it merely amends sections 114-115.[ref]

Id.[/ref] So, when the executives of Pandora say they would support the RESPECT Act if it provided for "full federalization,"[ref]

#irespectmusic and Fasten Your Seatbelts: Where Do We Go From Here on Pre-72?[/ref] what they really mean is they want DMCA safe harbor, fair use defenses, etc.

Then there's the biggest question of all: what about terrestrial analog broadcasters? For all these years, have the analog broadcasters been getting away with not paying something they should have been paying for? It seems that the decision in favor of Flo & Eddie points to "yes."[ref]It is worth noting there one decision holding that broadcasters do not have to pay performance fees for records they have purchased,

RCA Manufacturing Co. v. Whiteman 114 F.2d 86 Second Circuit Court of Appeals 1940, but this decision is not binding on the Courts in California.[/ref]

Not bad for a couple of hippies.