Google's Latest DMCA Abuse

This week, artist friendly websites such as The Trichordist[ref]Zoe Keating vs YouTube: The End of an Artist's Right to Choose Where Their Music Appears on The Internet.[/ref] and Digital Music News[ref]YouTube Is Removing Any Artist That Refuses to License Its Subscription Service...[/ref] spread the word about Google's bullying tactics against musicians, specifically cellist Zoe Keating. This blog has written about Zoe Keating before, in the post on streaming music services.[ref]Streaming Hits a Dam: Taylor Swift Says "Not So Fast," Sirius XM Loses Again and Flo and Eddie Sue Pandora[/ref] She epitomizes a forward thinking musician who embodies everything the internet seems to demand of present day musicians: a total DIY approach in which she is not signed to any record label, composes, records and distributes her music herself, even making certain songs free by uploading them to the Pirate Bay.[ref]Zoe Keating: What should I do about YouTube?[/ref]

Her view is simple: "Is such control [over one's catalog] too much for an artist to ask for in 2015?"

Apparently it is. She recounted, in great detail, Google's attempt to strong-arm her into signing up with their new pay streaming service, Music Play. According to Zoe's blog:

"Here are some of the terms I have problems with:

1) All of my catalog must be included in both the free and premium music service. Even if I don't deliver all my music, because I'm a music partner, anything that a 3rd party uploads with my info in the description will be automatically included in the music service too.

2) All songs will be set to "monetize", meaning there will be ads on them.

3) I will be required to release new music on YouTube at the same time I release it anywhere else. So no more releasing to my core fans first on Bandcamp and then on iTunes.

4) All my catalog must be uploaded at high resolution, according to Google's standard which is currently 320 kbps.

5) The contract lasts for 5 years."[ref]Id.[/ref]

And what if she doesn't go along with the new service? Then Google will block all the content on her existing YouTube channel and remove her Content ID privileges.[ref]Id.[/ref] What follows is directly from Zoe's transcript, to which I have added the identity of the speaker for the sake of clarity and cleaned up a few typos:

"[Zoe:] If I wanted to just let content ID keep doing its thing, and it does a great job at it and I'm totally happy with it and I don't want to participate in the music service, is that an option?

[Google:] That's unfortunately not an option.

[Zoe:] Assuming I don't want to, then what would occur?

[Google:] So what would happen is, um, so in the worst case scenario, because we do understand there are cases where our partners don't want to participate for various reasons, what we basically have to do is because the music terms are essentially like outdated, the content that you directly upload from accounts that you own under the content owner attached to the agreement, we'll have to block that content."[ref]Zoe Keating: Clarity[/ref]

So the implicit threat is that unless she signs up with Google's new system, they are going to block her existing videos from YouTube and throw her into "whack-a-mole" hell, in which she would be solely responsible for getting infringing content removed from YouTube. None of this would work if the DMCA provided for a "takedown and stay down" notification system, as noted previously on this blog.[ref]DMCA "Takedown" Notices: Why "Takedown" Should Become "Take Down and Stay Down" and Why It's Good for Everyone[/ref] She would not need the Content ID system at all, since if she was free from having to license her music to Google in order to get piracy protection, she could then release her music where and when and in whatever format she sees fit. Which should be the right of the artist to decide, shouldn't it?

It's just one more way in which the DMCA gets abused by Google,[ref]Google Is As Google Does: How Google Cheats Both Sides of the DMCA Takedown Process[/ref] a rather cynical use of their "safe harbor" protection to bully an independent musician into a one-sided contract.

Google's response to this adverse publicity was to smear Zoe to various media outlets calling her claims "patently false."[ref]YouTube Says Zoe Keating's Claims Are 'Patently False'...[/ref] What Google hadn't banked on was that Zoe had a complete transcript of the conversation, which in response to Google's smear tactics, is now available on her blog.[ref]Zoe Keating: Clarity[/ref] Google also demanded a retraction of the blog headline from Digital Music News.[ref]YouTube Says Zoe Keating's Claims Are 'Patently False'...[/ref] Again, what Google didn't count on was people quickly noticing that when they were using similar bullying tactics against various independent record labels in 2014, several news outlets reported virtually the same charge in their headlines, including Forbes,[ref]YouTube Is About To Delete Independent Artists From Its Site[/ref] The Guardian[ref]YouTube to block indie labels who don't sign up to new music service[/ref] and Time.[ref]YouTube Removing Indie Bands' Videos Ahead of Streaming Music Launch[/ref]

As a final note, what was very interesting was Zoe revealing that the terms of her contract with Google prevented her from disclosing how much Google paid her.

"[M]y monthly number of Pandora spins is also about 250,000. I'm allowed to talk about how much that pays, about $324 (sound recording + artist payment combined). It's a violation of my agreement to say how much a comparable number of YouTube plays pays."[ref]Zoe Keating: What should I do about YouTube?[/ref]

Wow, Google, that's some kind of commitment to transparency you've got there.

Here Come the Bogus Bonds

A scant two weeks ago, this blog wrote about the James Bond books going into the public domain in Canada, and other territories around the world.[ref]James Bond Enters the Public Domain! Is This the Work of SPECTRE?[/ref] The blog posited the possibility that new James Bond stories and books could be created in those territories.

Well, it didn't take long. According to the Bond fan site MI6-HQ,[ref]MI6: The Home of James Bond 007[/ref] a Canadian publisher announced plans to create new Bond stories.

"Independent Toronto publisher ChiZine Publications announces they will be publishing a new anthology of short stories featuring James Bond now that Ian Fleming's work has entered the public domain in Canada. The anthology, titled Licence Expired: The Unauthorized James Bond, will be edited by Toronto authors Madeline Ashby (vN, iD; Company Town) and David Nickle (Knife Fight and Other Struggles, The 'Geisters, Eutopia).

‘We want to feature original, transformative stories set in the world of Secret Agent 007,' says Nickle. ‘We're hoping our contributors will combine the guilty-pleasure excitement of the vintage Fleming experience with a modern critique of it.'

‘This is an opportunity to comment on the Bond universe from within it,' adds Ashby. ‘We're specifically looking for writers and stories that would make Fleming roll in his grave.'"[ref]Unauthorized collection of James bond stories to publish in Canada[/ref]

He might do just that.

Federal Judge Decides 1 + 1 = 1

There are two cases currently in litigation which are having issues with the rights inherent in a sound recording as opposed to the rights in the underlying musical composition. This is one of the issues in the lawsuits brought by Flo and Eddie, Inc. against various digital radio services, a topic which has been the subject of several blog posts here.

The first is the highly publicized case between the Estate of Motown legend Marvin Gaye, composer of the song "Got To Give It Up" and "After The Dance" against Pharrell Williams and Robin Thicke, the composers of the Robin Thicke hit song "Blurred Lines." In denying the Motion for Summary Judgment, the Judge made one crucial ruling; namely, that the copyrighted work was the lead sheet deposited with the Copyright Office, not the sound recording.

"[The Estate has] the burden to prove that they own the material…allegedly infringed. (citation omitted) [The Estate] have failed to produce evidence that creates a genuine issue as to whether the copyrights in "Got To Give It Up" and "After The Dance" encompass material other than reflected in the lead sheets deposited with the Copyright Office. (citation omitted) Accordingly for purposes of the analytic dissection performed in connection with this Motion, the lead sheets are deemed to define the scope of [The Estate's] copyrighted compositions."[ref]Pharrell Williams, et al. v. Bridgeport Music, Inc., et al. at pages 11-12[/ref]

This hurts the case of the Gaye Estate, since the recordings bear similarities that do not exist in the sheet music. The testimony is that Gaye wrote the song in the studio, and was not a fluent reader of musical notation.[ref]Id. at 2[/ref] It is unknown who prepared the sheet music deposited with the Copyright Office. At the time, the Copyright Office would not accept recordings to register musical compositions.[ref]Id. at 8[/ref]

The decision recognizes, correctly, that the copyright in the musical composition and the copyright in a sound recording are two distinct copyrights.

Thus, it is hard to reconcile that decision with another court's decision that only one award of statutory damages may be made for the illegal reproduction of a sound recording and the musical composition contained therein.[ref]Capitol Records, Inc. et al v. MP3Tunes LLC et al, 28 F. Supp 190 Southern District of New York, 2014[/ref] Here, even though the copyrights in the musical composition and the sound recording are owned by separate entities, the Court holds that "the composition and sound recording are subsumed in the same ‘work' for purposes of statutory damages, and the Plaintiffs are entitled to recover only once per work."[ref]Id. at 193[/ref] But they are not one work, they are two works, and the Copyright Act states they may recover statutory damages "with respect to any one work."[ref]17 USC 504 (c)[/ref] The Court rules this way, even after acknowledging that if the Plaintiffs had sued separately, they could each recover statutory damages.[ref]Capitol Records, Inc. at 192[/ref]

So, in other words, 1 + 1 = 1. Something about this decision doesn't add up.

Sophistry is a word that doesn't get used much these days, but it should. It is especially useful when engaging in arguments on the internet, where false and misleading statements are frequently the entire basis on which an argument rests.

Sophistry can be defined as:[ref]Your Dictionary: Sophistry[/ref]

1) [T]he deliberate use of a false argument with the intent to trick someone…

2) An argument that seems plausible, but is fallacious or misleading, especially one devised deliberately to be so.

It has become very fashionable among the anti-copyright forces to deny that copyrights are property. This denial has the instant effect of devaluing copyrights as a societal good. Which is exactly the intended effect.

According to the Electronic Frontier Foundation, copyrights and indeed all intellectual property aren't really property, they are some kind of pseudo-property [ref]Australia: You Wouldn't Steal a DVD, But You Would Block Websites and Suspend Internet Accounts[/ref] and do not deserve the same kind of protection afforded other property such as real property.

"Copyright is a limited set of rights that gives the owner the ability to prevent the public from making some uses of creative material for some length of time."[ref]Id.[/ref] …"[T]he use of the word "property" to tie these disparate areas of law together can mislead lawyers, judges, policymakers, and interested citizens into thinking that copyrights, patents and trademarks should be treated like real property."[ref]Intellectual Property: The Term[/ref]

This line of thinking can be traced back to law professor Lawrence Lessig, who is a "close ally" of EFF and was formerly on the EFF's Board of Directors.[ref]Larry Lessig on The Colbert Report[/ref] According to Lessig "IP is not P, but this truth is lost on us."[ref]Mossoff, A., Intellectual Property and Property Rights George Mason University Law and Economics Research Paper Series (Mossoff on Intellectual Property Rights as Property) citing Lessig, L. The Architecture of Innovation, 51 Duke Law Journal 1798 (2002)[/ref]

So are they right? Well, of course not.

The Copyright Act itself says copyrights are property. You would think something as obvious as this would not escape their notice, but apparently it has. The Copyright Act at 17 USC 201 (d) (1) states the following:

"The ownership of a copyright may be transferred in whole or in part by any means of conveyance or by operation of law, and may be bequeathed by will or pass as personal property by the applicable laws of intestate succession."

So not only does the Copyright Act state that copyrights are property, the law as a whole treats copyrights as property. Consider:

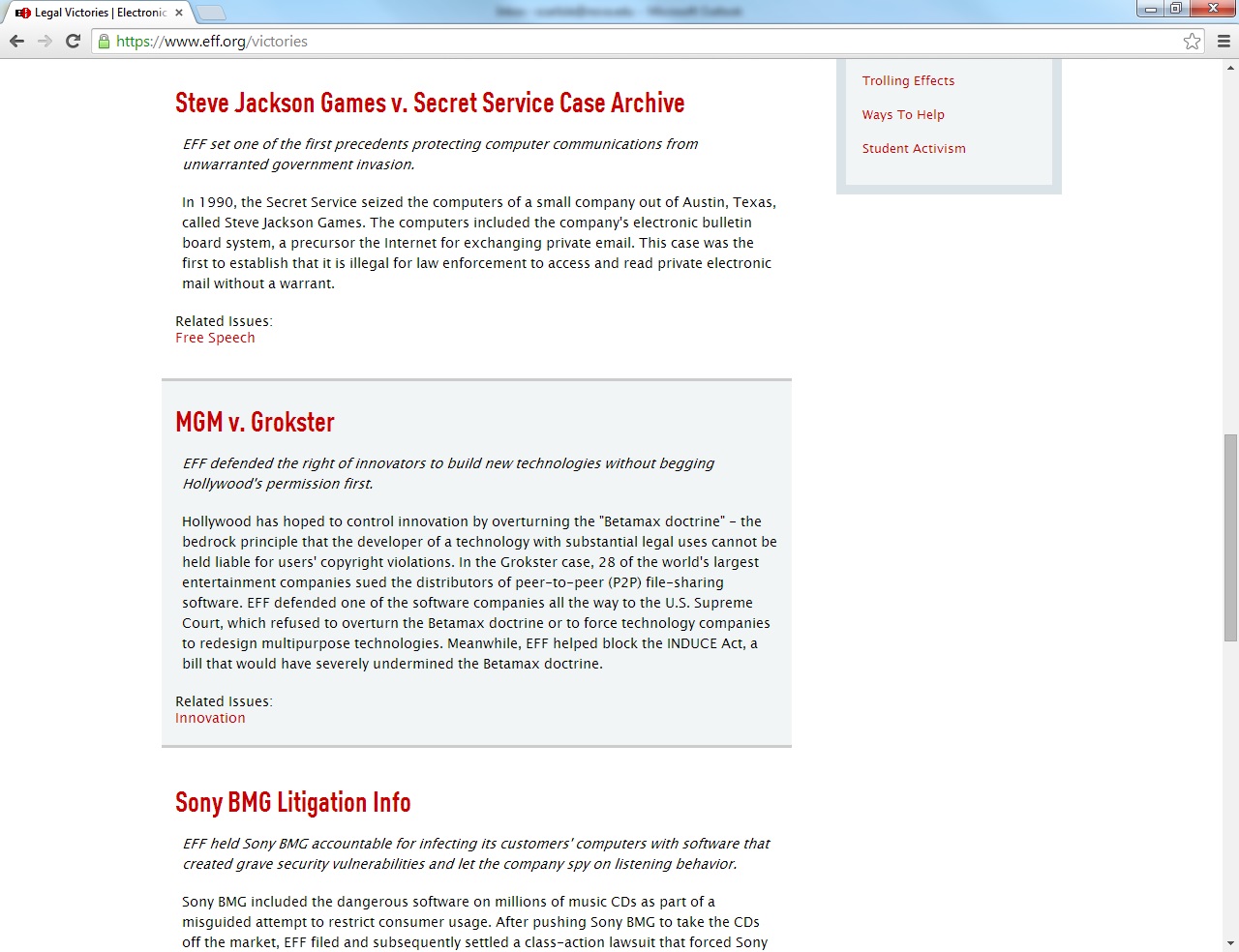

I should think that any legal organization that claims as a "victory" a 9-0 smack down at the Supreme Court tells you everything you need to know about the honesty and believability of that organization. Indeed, it is silly sophistry in its most indelible form.

I should think that any legal organization that claims as a "victory" a 9-0 smack down at the Supreme Court tells you everything you need to know about the honesty and believability of that organization. Indeed, it is silly sophistry in its most indelible form.

- Copyright can be bought and sold, in whole or in part, just like any other form of property[ref]17 USC 201 (d) (1)[/ref]

- Copyrights may be used as collateral for a loan[ref]In re: Peregrine Entertainment Ltd. 116 Bankruptcy Reporter 194, Central District of California 1990.[/ref]

- Copyrights may be levied upon to satisfy a judgment[ref]Hendricks and Lewis PLLC v. Clinton, WL 2808138 9th Circuit Court of Appeals 2014[/ref]

- The IRS will let you depreciate your copyright on the same basis as other property[ref]33A Am Jur 2d Federal Taxation 14656 "Copyrights and patents acquired in connection with the acquisition of a business are section 197 intangibles (see ¶14701 et seq.). A copyright or patent that isn't an amortizable section 197 intangible, that's used in a trade or business or held for the production of income, can be depreciated over the life of the patent or copyright from the time of its grant or acquisition by the taxpayer, using the straight-line method."[/ref]

- "…[D]eliberate unlawful copying is no less an unlawful taking of property than garden-variety theft…" Justices Breyer, Stevens and O'Connor, concurring opinion MGM v. Grokster 545 U.S. 913, Supreme Court of the United States (2005) (emphasis mine)

- : to take (something that does not belong to you) in a way that is wrong or illegal

- : to take (something that you are not supposed to have) without asking for permission

- : to wrongly take and use (another person's idea, words, etc.)

I should think that any legal organization that claims as a "victory" a 9-0 smack down at the Supreme Court tells you everything you need to know about the honesty and believability of that organization. Indeed, it is silly sophistry in its most indelible form.

I should think that any legal organization that claims as a "victory" a 9-0 smack down at the Supreme Court tells you everything you need to know about the honesty and believability of that organization. Indeed, it is silly sophistry in its most indelible form.

No Subjects

He's been shot, stabbed, tortured, threatened with castration (twice), dragged over a coral reef, seen his wife murdered on their wedding day, and yet, nothing has been able to stop James Bond. But now Bond faces his most powerful, unstoppable and implacable foe ever: the public domain.

While many today would regard James Bond as a cinematic hero, his origins are literary. His creator was an English newspaper journalist by the name of Ian Fleming. Like his literary creation, Fleming chased women, drank too much and smoked too much, leading to his early demise at the age of just 56 years old, on August 12, 1964.[ref]Ian Fleming[/ref] And therein lays the roots of Bond's predicament.

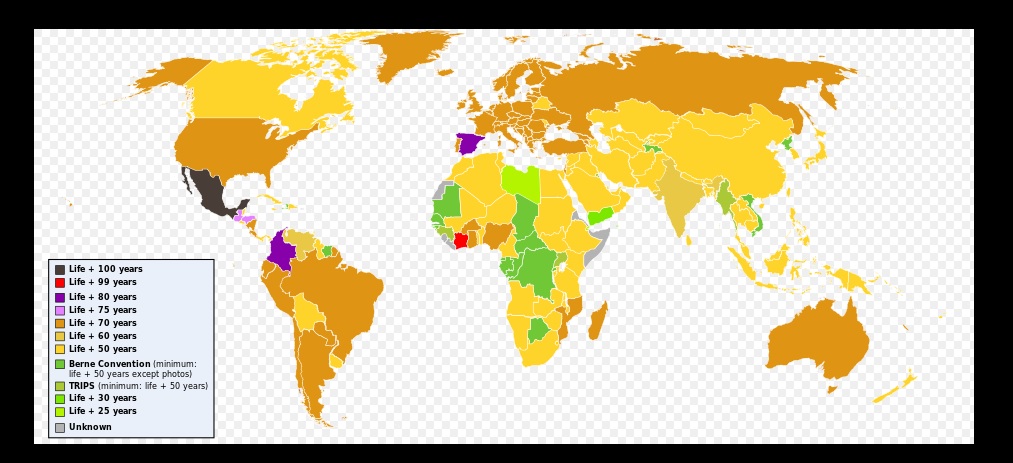

Earlier in this blog, I detailed the varying rationales behind copyright duration and in particular the restrictions of the Berne Treaty.[ref]Copyrights Last Too Long! (Say the Pirates): They Don't; And Why It's Not Changing Anytime Soon[/ref] Recall that, at a minimum, Berne Treaty signatories are required to establish a base line of copyright protection of the life of the author plus 50 years after death.[ref]Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works (Paris Text 1971)[/ref] Now the European Union, along with the United States, has expanded this to life of the author plus 70 years, but not every Berne nation has followed suit. There are many nations who still adhere to the "life plus 50" rule of copyright duration, including Canada, Japan, New Zealand, South Africa and Thailand.[ref]List of countries' copyright lengths[/ref] Here is a quick visual aid to show where copyright protection is life plus 50 years or less.[ref]List of countries' copyright lengths - World copyright terms[/ref]

Created by Balfour Smith, Canuckguy, Badged and used under a CC-BY License

And now, James Bond is in the public domain in every one of those countries shaded light yellow or less. Dying in 1964, Ian Fleming's 50 years of posthumous protection ended December 31, 2014. Further, Fleming's early demise has now worked against him. The Bond novel The Man with the Golden Gun and the short story collection "Octopussy and the Living Daylights" were both published posthumously,[ref]Ian Fleming's James Bond Titles[/ref] so these works did not even get 50 years of copyright protection. Nevertheless, all 12 James Bond novels and two collections of short stories, along with all the elements contained in them are all free for the taking in those Berne countries adhering to the "life plus 50" term.

Which leads to the interesting prospect that there might be new "unofficial" James Bond books written and even new "unofficial" James Bond movies or perhaps a television series. But this is trickier than it sounds on first consideration.

The Bond movies are certainly still under copyright in the majority of the world, and according to this article, even in Canada.[ref]What Does It Mean That James Bond's In the Public Domain In Canada?[/ref] However, my research has failed to uncover the precise section of Canadian copyright law that provides for this. So whatever you did, you could copy anything created by Fleming in the books, but not copy anything that is solely the creation of the films, such as the character "Jaws" or the famous "007" gun barrel logo, as discussed below.

Of course, someone absolutely will try. Adjusted for inflation, the Bond films are the highest grossing film series in motion picture history.[ref]Film Franchises - Pottering on, and on[/ref] The literary Bond also continues. Ian Fleming Publications has authorized 37 different novels and short stories by six different writers.[ref]James Bond books[/ref]

So what can you use? Yes, you could identify him as "007". Yes, you could have your Bond utter the famous "The name's Bond…James Bond." as he does introduce himself this way in the Fleming books. You could have your Bond drive an Aston Martin DBIII, as Bond drives this car in Goldfinger (but no other book).[ref]The James Bond Bedside Companion, by Raymond Benson, Dodd Mead and Co., 1984 at page 63[/ref] Your Bond could use a Walther PPK as a gun, first issued to him in Doctor No[ref]Id. at 65[/ref] and order his martinis "shaken and not stirred" as he does in Doctor No,[ref]Shaken, not stirred[/ref] although references to this method of preparation go as far back as the first novel Casino Royale.[ref]The James Bond Bedside Companion at page 69[/ref]

Some uses are a clear "can't use." The Bond of the books never tosses out bon mots after a narrow escape, a creation of the films. Miss Moneypenny never engages Bond in the suggestive repartee' that she does in the films. And just in case you were so inclined, no white cat for Blofeld, and no bald Blofeld either. In the books, Blofeld has hair, with no feline in sight.

From there it gets murky rather quickly. The books are nearly devoid of the gadgets that populate the cinematic James Bond universe. So a gadget laden Bond might cross the line, or might not. The Aston Martin DBIII from Goldfinger (the book) is equipped with some gadgets (e.g. a radio tracker), but nothing to the extent portrayed in the film. Likewise, the character known as "Q" from the films has been addressed as Major Boothroyd, who is a character from the books. Yet, to the contrary, there is no character known as "Q" in the Fleming books. Is a "gadget briefing" that was a staple of the movies acceptable as long as he is called "Major Boothroyd" and not "Q"? Clearly, whoever will try to use the Fleming material is up to a considerable challenge.

Further consider this example: Bond's best friend and compatriot is a CIA agent by the name of Felix Leiter, and he appears in several of the films. However, in just the second book, Live and Let Die, Leiter is fed to sharks and loses part of his right arm and leg. Thereafter, he has a prosthetic leg and a mechanized hook to replace his hand. He has never been portrayed in the movies this way or as having any disability at all, even after the shark scene was later used in the Bond film License to Kill (the scene does not appear in the film version of Live and Let Die at all). So if one were to include Felix Leiter, is it necessary to include his disabilities to avoid poaching on the film series? Or is he the Felix Leiter of the book Casino Royale, and pre-shark?

Also, the material in the Fleming books would have to be compared against the entire film series, not just the movie of the same name. Starting with You Only Live Twice on through until Casino Royale, the Bond movies had little or nothing to do with the books with which they share their title, save for the names of the major characters and some settings, the lone exception being On Her Majesty's Secret Service, which does closely follow the plot of the book. However, odd bits and pieces did crop up in later films. For example, a scene in which Bond and the heroine are dragged over a coral reef occurs in Live and Let Die, but does not turn up in the films until For Your Eyes Only. The character of Milton Krest and his boat the WaveKrest occur in the short story collection "For Your Eyes Only" but turn up later in the film License to Kill.

And then there is the whole problem with SPECTRE. The book in which the criminal organization first appears, along with Bond's arch-nemesis Ernst Stavro Blofeld is Thunderball. This book was the subject of a bitter court fight between Fleming, Kevin McClory and Jack Wittingham. The latter two were co-writers with Fleming of an unmade Bond movie script title Longitude 78 Degrees West.[ref]See generally, The Battle For Bond, by Robert Sellers, Tomahawk Press 2008[/ref] It was alleged that Fleming lifted large parts of the co-written script, and then inserted them in to a book attributed solely to Fleming.[ref]Id.[/ref] The parties settled out of court in 1963.[ref]Id.[/ref] The Thunderball book remained attributed to Fleming, with the proviso that a note was inserted into the book that it was based on the screenplay written by the three men.[ref]Id.[/ref] The Thunderball film rights were awarded to McClory along with all the material contained in all of the drafts of the script.[ref]Id.[/ref] McClory died only recently, in 2006,[ref]Kevin McClory[/ref] so his copyrights are very much alive. For their part, EON Productions, the Bond film producers, have now acquired all of McClory's rights from his estate.[ref]Id.[/ref] This allows the SPECTRE organization to return for the upcoming Bond film of the same name.

Yet oddly enough, this leaves EON in a bit of a pickle. They, for decades, have vigorously contested in more than one lawsuit that McClory merely had the films rights to Thunderball and nothing more. After all, Fleming used both SPECTRE and Blofeld (seemingly without objection) in two subsequent novels. For his part, McClory later claimed copyright over all aspects of SPECTRE, including Blofeld, with this leading EON to abandon all mention of them after the film Diamonds Are Forever. Attempts by McClory to assert these rights were defeated by EON and later affirmed by the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals in Danjaq, LLC. V. Sony.[ref]256 F.3d 942, Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, 2001[/ref]

So, let's project that a Canadian writer wishes to write a new Bond book, including SPECTRE and Blofeld. In the inevitable lawsuit, EON will assert the rights obtained from McClory's estate. However, the writer will be able to counter with piles of court documents in which EON has claimed the exact opposite, namely that McClory had no rights. To the extent that Fleming had any rights in either SPECTRE or Blofeld, the writer will point out that they have now passed into the public domain.

So what rights can be exploited, and how? The books themselves may be freely reprinted and distributed, but only in those nations which adhere to the life plus 50 copyright term. For example, in the United States, infringement includes importation of copies acquired abroad, if they would be infringing if made domestically.[ref]17 USC Section 501 and 602[/ref]

It also seems clear that new James Bond books could be written, and only distributed in the restricted territories as noted above. Ian Fleming Publications have had their rights lapse, and EON Productions, the makers of films, not books, would not seem to have any standing (i.e. legal injury) that would give them the ability to file a viable lawsuit.

Yet, here is where the internet comes into play. If e-books are made in Canada, yet purchased in the United States, would this not constitute infringement? It seems that it would. Yet just how would a Canadian publisher know, without directly asking, where the purchaser is located? Is there an affirmative duty upon the Canadian publisher to find out this information?

Now let's say the product is a motion picture, television series or web series. Being audio-visual presentations, the producers would have to carefully craft their product to ensure it does not infringe on the original material created by EON Productions, as noted above. If a TV program is broadcast in Canada, but "leaks" over the border, is this infringement? If the web series is streamed, does the producer have an affirmative duty to ensure that it is not streamed into "life plus 70"countries? Hard to say at this juncture, but I'm sure we'll find out. EON has not hesitated to use the legal system to protect their brand, most recently against Universal Studios.[ref]MGM Settles James Bond Copyright Lawsuit Over Universal's 'Section 6'[/ref]

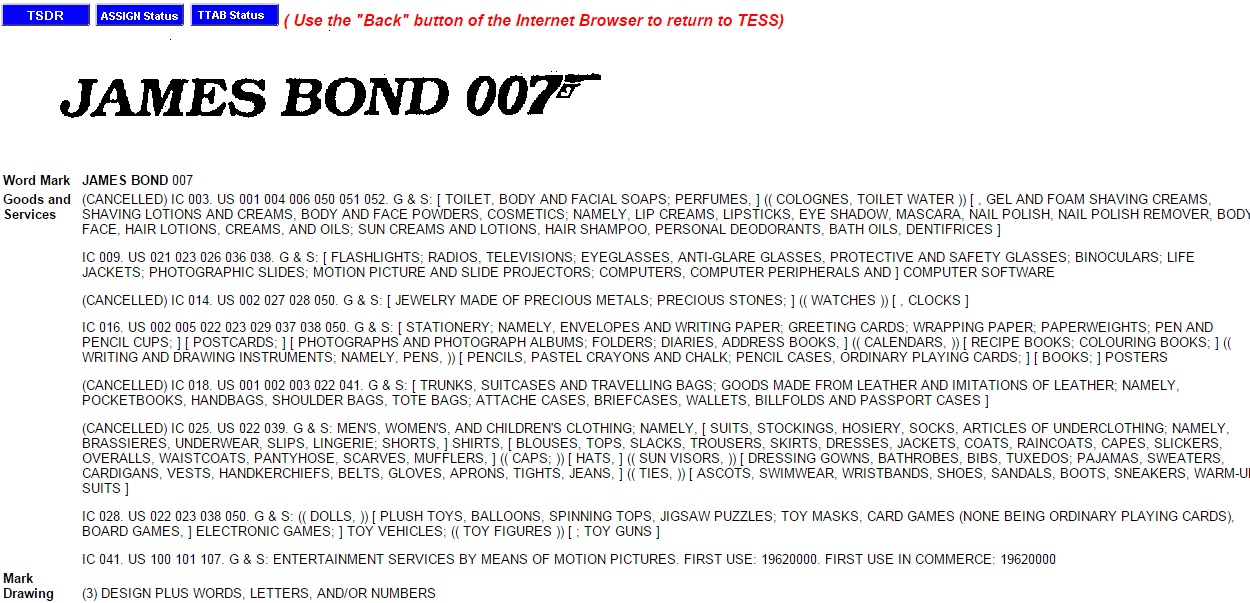

Is there potentially any relief available in the arena of trademark law? This method was discussed in a previous blog post about Mickey Mouse and the public domain.[ref]Mickey's Headed to the Public Domain! But Will He Go Quietly?[/ref] According to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, the name "James Bond" is not currently subject of a trademark registration, but "James Bond 007" is. This is not a plain text mark, but stylized mark featuring the familiar "007" gun barrel design. While the registration includes "Entertainment Services by Means of Motion Pictures" it seems that they have limited themselves to use of the mark as drawn. Here is a screen shot of the James Bond registration:

As discussed in the Mickey Mouse blog post, EON faces several hurdles on a trademark theory. First, unlike Mickey, he does not have a stylized appearance, having been portrayed (officially) by six different actors. Next, Bond's "creator" or "source" is Ian Fleming, not EON. Also, in order to be protected as a character, Bond needs to have achieved secondary meaning. As noted above, certain traits of Bond's character are indeed the property of EON, but many were created by Ian Fleming, and the Bond films have been made by three separate film studios, United Artists, MGM and now Sony/Columbia.

Anyone who undertakes to make new Bond works, especially audio-visual works, will need to have a great deal of nerve, the willingness to engage in a long and intense fight and deep pockets to stave off the inevitable litigation.

Hmmm. Sounds like SPECTRE to me.

No Subjects

Time to update several topics that were the subject of blog posts in 2014.

The Future of the Georgia State Case

Back on October 24, 2014, this blog discussed the impact of the ruling in Cambridge University Press v. Patton, a/k/a the "Georgia State" case.[ref]Georgia State and the Boundaries of Academic Fair Use: From Bright Line Test to...Maybe[/ref] The case had the effect of eliminating "bright line" rules when engaging in fair use analysis, but reaffirmed the preferences afforded to not-for-profit educational institutions when considering the question of fair use. On January 2, 2015, the 11th Circuit denied the request of the publisher plaintiffs for a rehearing of the case. (Link currently unavailable) Georgia State also filed for rehearing, which was also denied. The denials of the rehearing request were made without comment, leaving the previous opinion intact and unmodified. So, what options do the publishers have at this point? The first would be a direct appeal to the Supreme Court of the United States. This is unlikely to succeed for several reasons. The SCOTUS has absolute discretion in what cases it hears, and only accepts a tiny fraction of those cases it is asked to hear. So, the publishers must demonstrate some compelling reason why the Court should hear the case at this time. The 11th Circuit opinion only re-affirms what the SCOTUS has already held: there are no bright line rules and every claim of fair use must be examined on a case by case basis. Plus, to my knowledge, there are no conflicting opinions from any of the other circuits, a prime reason that the SCOTUS chooses to accept a case. These factors don't mean the publishers won't try, but it is a huge long shot in terms of potential success. Next would be to re-try the case. This will be unpalatable to the publishers. First and foremost, they would be re-trying the case in front of the same Judge who ruled against them on the first trial. Next, while only one Appellate Judge said he thought it was clear that Georgia State was not engaging in fair use, the other Judges only disagreed with the methodology of how the Judge arrived at her decision, not the decision itself. She could stay within the guidelines set by the 11th Circuit and largely arrive at the same conclusion. This, of course, would lead to another appeal, all the while consuming large amounts of time and incurring huge amounts of attorneys' fees in the process. The publishers could try to settle the case. While this has a facial appeal as a strategy, I feel that this will not work. Remember, since Georgia State is an arm of the State Government of Georgia, they have sovereign immunity from having to pay damages. The publishers have no leverage there. What the publishers really want is a ruling that the 1976 Classroom Copying Guidelines are the maximum allowable copying. Not only is Georgia State not going to agree to this since it is so restrictive, it flies in the face of the 11th Circuit ruling of "no bright line rules." So, even if they were to agree to it, the Judge could not enter a judgment ruling this in the face of the 11th Circuit precedent to the contrary. The same fate befalls a ruling that the course pack cases are equivalent to online posting. The 11th Circuit also ruled that this is not so. Lastly, Georgia State long ago changed their policy with regards to the posting of copyrighted materials on line. So what is there that Georgia State can give up in settlement that the publishers would want? Nothing that I can see. Which leads me to the last strategy, dismiss the case and try again in a different court. This one is a bit tricky since it has the distinct odor of forum shopping. The plaintiff(s) would have to be different, as the 11th Circuit ruling is binding on the current publisher plaintiffs. The location would have to be outside of Florida, Georgia and Alabama for the same reason, all District Court Judges in those states are currently bound by the 11th Circuit opinion. The ultimate strategy is to get the 11th Circuit ruling over-turned, and the only institution that could do that is the Supreme Court of the United States. The best way to do this, as noted above, is to create a conflict between circuit courts. So, the new plaintiff-publisher would have to file suit against a different educational institution or library. Perhaps they might choose as their target one of the many "for profit" universities, who are less sympathetic as a defendant than a not-for-profit institution. The new plaintiffs would have to win a judgment in their favor, and then prevail on the inevitable appeal. This would then create the necessary conflict that might cause the SCOTUS to take up the issue. The ball, as the cliché goes, is in the court of the publishers.Google Censors the Internet (If it's Profitable)

This blog has long been critical of Google and its self-serving and sometimes underhanded approach to processing DMCA takedowns.[ref]Google Is As Google Does: How Google Cheats Both Sides of the DMCA Takedown Process & Google Blacklists 10,000 Sites a Day; Why Doesn't It Blacklist Pirate Sites?[/ref] Now that 2014 is in the books, let's take a look back. According to the website Torrent Freak, Google processed over 345 million takedown notices in 2014.[ref]Google Asked to Remove 345 Million "Pirate" Links in 2014[/ref] The math is easy. This amounts to nearly 1 million takedown notices per day which are being served on Google. I asked way back on July 24, 2014, why doesn't Google see this as a tremendous waste of human resources? [ref]DMCA "Takedown" Notices: Why "Takedown" Should Become "Take Down and Stay Down" and Why It's Good for Everyone[/ref] Would it not be more profitable to make Google's policy "take-down and stay-down?" Apparently not. As previously pointed out on this blog, Google will happily take down or block access to websites for a variety of reasons.[ref]Google Blacklists 10,000 Sites a Day; Why Doesn't It Blacklist Pirate Sites?[/ref] As this article makes vividly clear, Google is also more than willing to censor websites and suppress free speech, if it is in Googles best business interest to do so.[ref]Google: The reluctant censor of the Internet[/ref] This is what Google claims that it does: "For our own websites and for the Internet as a whole we have worked tirelessly to combat internet censorship around the world," Google co-founder Sergei Brin said in a 2011 blog post. "I am proud of the role Google has played."[ref]Id.[/ref] According to this money.cnn.com article, this is what Google really does: "… In Turkey, Google takes down links to sites that defame the country's founder, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk -- that's illegal there. In Thailand, denigrating the Thai monarch is against the law, so Google blocks YouTube videos in Thailand that ridicule King Bhumibol Adulyadej."[ref]Id.[/ref] "In 2010, Google became so exasperated by China's censorship demands that it pulled its business out of the country altogether. At the time, Google said it would abide by censorship demands from democratically elected governments, (emphasis added) but Chinese people did not have the ability to choose the leaders making the censorship demands…Yet Google plays both sides of the fence. Though it doesn't operate in China, it does operate in other countries with dictatorships or monarchies, including Zimbabwe and Thailand. Google declined to comment for this story."[ref]Id.[/ref] The reality is Google is more than happy to censor the internet and squash free speech, as long as it is profitable and in their best interests. So, the next time Google trots out the old "we don't want to suppress free speech" canard as to why they won't de-list pirate sites, you'll recognize what Google is trying to feed you: a two faced baloney sandwich.Active Nashville Songwriters Drop 80%

Back on August 13, 2014, this blog did an in depth analysis of the economic harm done to copyright creating entities from internet piracy.[ref]Copyright Piracy and the Entertainment Industries: Is the Effect Massive of Negligible?[/ref] Last Monday, The Tennessean released this article on Nashville songwriters, titled Nashville's Musical Middle Class Collapses.[ref]Nashville's musical middle class collapses[/ref] This article presents some fairly sobering statistics on what happened to songwriters in "Music City" in the internet age. "Since 2000, the number of full-time songwriters in Nashville has fallen by 80 percent, according to the Nashville Songwriters Association International. Album sales plummeted below 4 million in weekly sales in August, which marked a new low point since the industry began tracking data in 1991. Streaming services are increasing in popularity but have been unable to end the spiral. The result has been the collapse of Nashville's musical middle class — blue-collar songwriters, studio musicians, producers and bands who eke out a living with the same lunch-pail approach that a construction professional brings to a work site."[ref]Id.[/ref] So, tell me again how internet piracy does not have a negative economic effect on the music industry, but actually helps it?

No Subjects