Earlier this year, there was another skirmish in the long running battle over copyright in recipes. The intriguingly titled case of Tomaydo-Tomahhdo,LLC v. Vozary[ref]2015 WL 410712[/ref] once again examined the question of: are recipes copyrightable? And if so, what parts?

I have long maintained that the idea of copyright in a recipe violates two main principles of the copyright law, namely the lack of protection for facts[ref]Harper and RowPublishers v. Nation Entertainment 471 US 539 Supreme Court of the United States 1985 at 556[/ref] and the lack of protection for procedures, processes and systems.[ref]17 USC 102(b)[/ref] A recipe is little more than a listing of the necessary ingredients, along with instructions on how to combine them. This is not, by the very terms of the copyright act, capable of copyright protection.

This is why your cookbook is likely to be festooned with photographs and illustrations as well as lengthy asides ruminating on the history of the porcini mushroom. These are unquestionably the proper subject matter of copyright and thus grant the cookbook copyright protection. But no one buys a cookbook for the illustrations; they buy it for the recipes. Now, the overall collection of recipes, as a compilation,[ref]17 USC 103(a)[/ref] will qualify for copyright protection, but this will not necessarily protect an individual recipe from being copied.

Making matters worse, if you really wanted to protect your recipe from being copied, registering it for copyright might be the last thing you would want to do. In order to register, you would have to send a copy of it to the copyright office, which of course would make it a public record. The most popular recipe in America, the formula for Coca-Cola, is also one of America's most closely guarded trade secrets.[ref]Coca-Cola formula[/ref] Major chain restaurants also keep their recipes a secret. Here, for example, is the "recipe" for one of my favorite chain salads, The Cheesecake Factory's "Chinese Chicken Salad." Note that it omits the most important part: the necessary ingredients and how to make the salad dressing![ref]Chinese Chicken Salad[/ref] Ditto for another one of my favorites: The "Santa Fe Salad." In both cases, they tell you to buy the dressing from a store. How helpful.

Yet the Copyright Office itself is not quite as certain as I am on this subject. According to the Copyright FAQ's:

"How do I protect my recipe?

A mere listing of ingredients is not protected under copyright law. However, where a recipe or formula is accompanied by substantial literary expression in the form of an explanation or directions… there may be a basis for copyright protection."[ref]How do I protect my recipe?[/ref]

To which I say, how can you have "substantial literary expression" in a recipe? One of the guiding principles of copyright is that copyright will not protect expression where there is only a limited number of ways you can state something.[ref]Landsberg v. Scrabble Crossword Game Players, Inc., 736 F.2d 485, 489 (9th Cir.1984)[/ref] If the final direction is to "bake for 30 minutes at 350 degrees," how many different ways can you say that?

Also consider that cooking contains numerous "terms of art," or words that have specific meanings. "Bake," "broil" and "grill" all indicate ways of heating something, but each refers to a specific method by which this is accomplished. (If there's any doubt, try broiling a soufflé and see if you are pleased with the results). Or you could examine the words "simmer," "reduce," "whisk" or "boil," all which have specific culinary meanings. How would you explain how to cook something without using one or more of those terms if the recipe called for it?

Says the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals:

"The idea contained in that statement cannot be expressed in a wide variety of ways. Just about any subsequent expression of that idea is likely to appear to be a substantially similar paraphrase of the words with which [Plaintiff] expressed the idea. Therefore, similarity of expression may have to amount to verbatim reproduction or very close paraphrasing before a factual work will be deemed infringed."[ref]Id. citing 1 M. Nimmer, Nimmer on Copyright, § 2.11[A]–[B] (1968)[/ref]

The leading case involving recipes comes from the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals, Publications International Ltd. V. Merideth Corp.[ref]88 F.3d 473 Seventh Circuit Court of Appeal 1996[/ref] The case has been cited by other Courts in denying copyright protection to recipes,[ref]See e.g. Harrell v. St. John 792 F.Supp2d 933 District Court for the Southern District of Mississippi 2011[/ref] including Tomayto-Tomahhdo mentioned above. The Court in Merideth held that the recipes in question were not copyrightable, namely:

"The recipes involved in this case comprise the lists of required ingredients and the directions for combining them to achieve the final products. The recipes contain no expressive elaboration upon either of these functional components, as opposed to recipes that might spice up functional directives by weaving in creative narrative."[ref]Merideth. at 480[/ref]

Ah, but there's a loophole! "[R]ecipes that might spice up functional directives by weaving in creative narrative." And it's a Texas-sized loophole at that.

Consider the case of Barbour v. Head, a case from the Southern District of Texas.[ref]178 F.Supp2d 758, District Court for the Southern District of Texas 2001[/ref] The Judge, with tongue firmly in cheek and frequently tossing off humorous asides, (referring to the cookbook in the Merideth case as "No doubt a citified book of no use fer [sic] the varmints cooked hereabouts") refuses to dismiss the lawsuit based upon the copying of recipes, based upon the inclusion of fanciful names for the recipes ("Cattle Baron Cheese Dollars" and "Gringo Gulch Grog") and non-instructional verbiage ("this is the secret to the unique taste") that nonetheless wound up being copied verbatim by the Defendants.

Ultimately, this loophole will do little to protect the actual recipe from being copied. As long as one simply copies the ingredients and the instructions on how to combine them, and eliminates any unnecessary extra verbiage, the recipe still may be freely copied, and it will not get copyright protection.

There are considerations beyond the mere letter of the law. As this article from Plagiarism Today points out, in the age of the celebrity chef, being caught lifting someone else's recipe might damage your reputation and do serious harm to your career.[ref]Recipes, Copyright and Plagiarism[/ref]

Otherwise, it's a case of "if you can't stand the cheats…stay out of the kitchen."

No Subjects

The verdict in the "Blurred Lines" case surprised a lot of people, myself included. I incorrectly predicted that the Pharrell Williams-Robin Thicke camp would prevail,[ref]The Fight over "Blurred Lines:" What Parts of a Song are Copyrightable?[/ref] and certainly did not foresee the millions of dollars in damages that were assessed by the jury. As a general rule, having served on a jury myself, I do not criticize jury verdicts. The jury hears all the evidence, not just what is reported in the news media. But here, where the two works are readily available for examination, and having a background in music as well as law, I will have to break my rule and say I disagree with the jury's verdict.

It turns out that I was not alone in my thinking. Indeed, after the verdict, many musicians and composers lit up the internet with posts about how wrong the verdict was. I was unable to find a side by side comparison of the melodies in musical notation. To my ear, though, the melodies are not all that similar. The lyrics are completely different, but that is not unusual. Most cases of music infringement come down to the notes sung, not the lyrics. This was the case in the George Harrison "My Sweet Lord" case, the Bee Gees "How Deep Is Your Love" case and the recent settlement between Sam Smith and Tom Petty, over "Stay With Me."[ref]Tom Petty on Sam Smith Settlement: 'No Hard Feelings. These Things Happen'[/ref] In all three cases, the lyrics were completely different. More about the latter two further on.

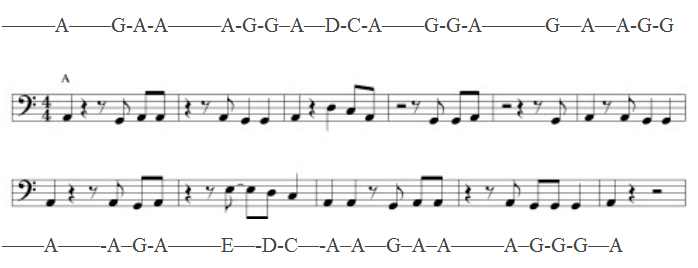

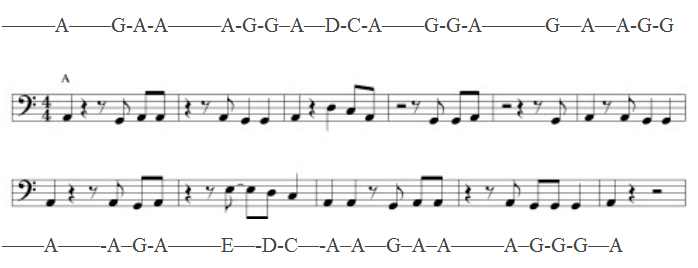

With regard to "Got To Give It Up" (GTGIU), I did find this very thorough and well-reasoned analysis by musicologist Joe Bennet.[ref]Did Robin Thicke steal 'Blurred Lines' from Marvin Gaye?[/ref] One of the claimed similarities was the bass line. Here is a comparison of the two bass lines. The bass line from "Blurred Lines" (BL) was transposed from G major into the key of A minor, and GTGIU was transposed from A major to A minor. This was done so that any similarities should be fairly obvious and avoiding needing a key signature.[ref]Id.[/ref] These are Mr. Bennet's work for which I give him full credit and my sincere appreciation. Sometimes a visual reference can make complicated issues clearer.

This is the bass line for "Blurred Lines."

This is the bass line for "Blurred Lines."

I just don't hear it, and I certainly don't see it. The GTGIU bass line runs for 11 bars, while the BL repeats on an eight bar cycle. The BL bass line is far more sparse and repetitious, and the octave jumping flourish at the end has been a staple of funk/disco music for at least 40 years, maybe more.

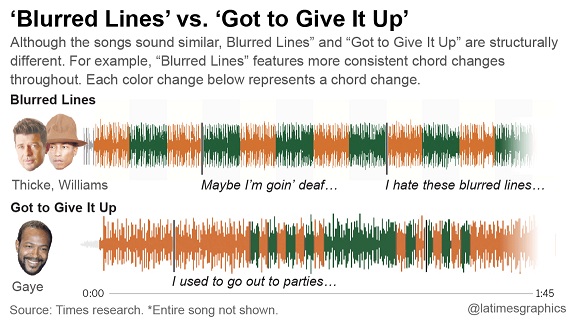

Then there is the chord progression, or lack thereof. BL is basically what musicians call a "vamp," a cycle of repeated chords that does not change. This chart comes courtesy of the LA Times newspaper,[ref]'Blurred Lines' vs. 'Got to Give It Up'[/ref] and shows that the phrasing of the chords is very dissimilar.

Music theory graduate Dan Bogosian put it like this:

"There are literally only two chords in "Blurred Lines;" a lot of people have inappropriately labeled it G to D, but it's actually C/G to D. That's one of the gratifying things about the song: because the C chord doesn't have a C in the bass, it maintains tension throughout… the genius of Williams and Thicke has the bass doing one thing, and everything else doing another."[ref]A Music Theory Expert Explains Why the "Blurred Lines" Copyright Decision Is Wrong[/ref]

"This progression is known as IV to V, and it's one of the most common set of harmonies in all of music; it happens in every single doo-wop song, and in roughly half of all pop songs and classical compositions. A bass line that never hits the root or truly resolves is unusual nowadays, but it's actually the defining trait that makes the opening moment of "Blurred Lines" funky."[ref]Id.[/ref]

"On the other hand, "Got to Give it Up" has twice as many chords as Thicke's (four versus two), and includes the IV to V chord progression on every repeat. Each repeat resolves, never using the strange tension in the bass the way "Blurred Lines" does."[ref]Id.[/ref]

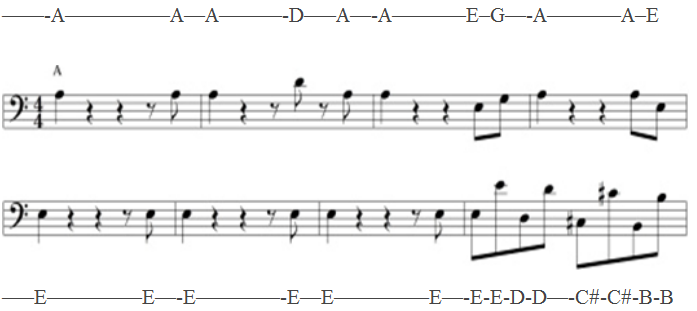

Another allegation is that Gaye's "distinctive cow bell" rhythm was borrowed.[ref]Did Robin Thicke steal 'Blurred Lines' from Marvin Gaye?[/ref] Back to musicologist Joe Bennet, who prepared these charts:

Here is the cowbell part from GTGIU:

I just don't hear it, and I certainly don't see it. The GTGIU bass line runs for 11 bars, while the BL repeats on an eight bar cycle. The BL bass line is far more sparse and repetitious, and the octave jumping flourish at the end has been a staple of funk/disco music for at least 40 years, maybe more.

Then there is the chord progression, or lack thereof. BL is basically what musicians call a "vamp," a cycle of repeated chords that does not change. This chart comes courtesy of the LA Times newspaper,[ref]'Blurred Lines' vs. 'Got to Give It Up'[/ref] and shows that the phrasing of the chords is very dissimilar.

Music theory graduate Dan Bogosian put it like this:

"There are literally only two chords in "Blurred Lines;" a lot of people have inappropriately labeled it G to D, but it's actually C/G to D. That's one of the gratifying things about the song: because the C chord doesn't have a C in the bass, it maintains tension throughout… the genius of Williams and Thicke has the bass doing one thing, and everything else doing another."[ref]A Music Theory Expert Explains Why the "Blurred Lines" Copyright Decision Is Wrong[/ref]

"This progression is known as IV to V, and it's one of the most common set of harmonies in all of music; it happens in every single doo-wop song, and in roughly half of all pop songs and classical compositions. A bass line that never hits the root or truly resolves is unusual nowadays, but it's actually the defining trait that makes the opening moment of "Blurred Lines" funky."[ref]Id.[/ref]

"On the other hand, "Got to Give it Up" has twice as many chords as Thicke's (four versus two), and includes the IV to V chord progression on every repeat. Each repeat resolves, never using the strange tension in the bass the way "Blurred Lines" does."[ref]Id.[/ref]

Another allegation is that Gaye's "distinctive cow bell" rhythm was borrowed.[ref]Did Robin Thicke steal 'Blurred Lines' from Marvin Gaye?[/ref] Back to musicologist Joe Bennet, who prepared these charts:

Here is the cowbell part from GTGIU:

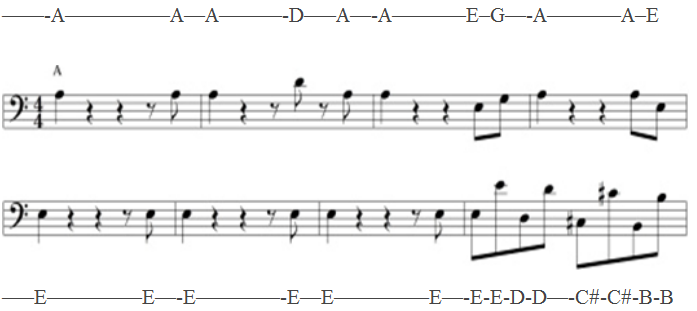

Bennet says there are actually two cowbell parts in BL. He transcribes them as follows:[ref]Id.[/ref]

Bennet says there are actually two cowbell parts in BL. He transcribes them as follows:[ref]Id.[/ref]

The only similarities are the first two notes, and the first eighth note of the second bar. Everything else is different.

Back to Dan Bogosian:

"Got To Give It Up" opens with a melodic run that spans the same musical distance as the entire Thicke song. It's actually a perfect vehicle to show off Gaye's voice; the run is challenging by itself, and he routinely jumps up and down four scale notes — no easy feat for an untrained vocalist. "Blurred Lines" is the opposite: the reason everyone seems to be able to sing along with Thicke…[is] that they're sung entirely within the first five notes of the major scale (i.e. the pentascale)."[ref]A Music Theory Expert Explains Why the "Blurred Lines" Copyright Decision Is Wrong[/ref]

"To put it in more digestible terms: Thicke's vocal performance is comparable to Ringo Starr's in "Yellow Submarine," and Marvin Gaye was one of soul music's greatest talents because of vocal parts like "Got To Give It Up."[ref]Id.[/ref]

"Throwing aside that Marvin Gaye's song is nearly three times as long as "Blurred Lines," it's still obvious that the melodies, harmonies, chord progressions, and rhythms are different."[ref]Id.[/ref]

Remember the test for infringement is "substantial similarity" not just similarity. What does substantial similarity look and sound like? Here is a very recent example; Tom Petty and the Heartbreaker's "I Won't Back Down" and Sam Smith's "Stay With Me" (which, by the way, won a Grammy as Song of the Year,[ref]Stay with Me (Sam Smith song)[/ref] an award given to the songwriter. Oops). After adjusting for pitch and tempo, this mash-up shows that the two songs can be sung right over each other, and the choruses are nearly identical.

https://youtu.be/qkcZV97O3pw

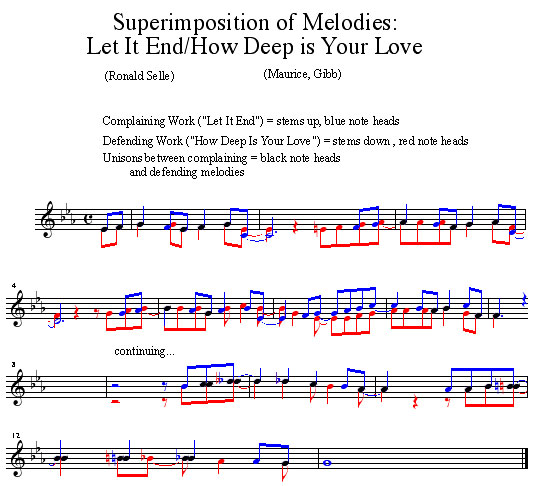

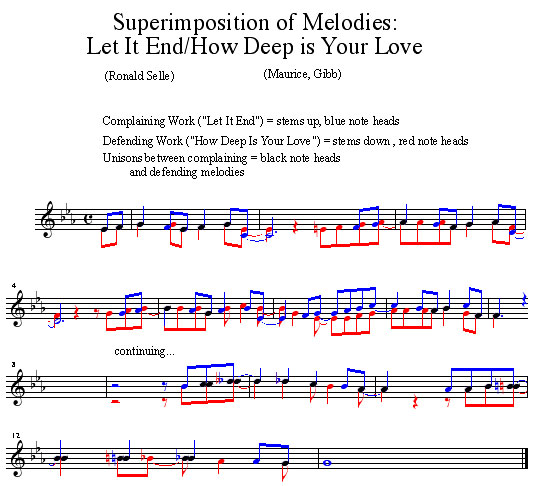

Here is a transcription of the two competing songs in the "How Deep Is Your Love" case. (I have forgotten where I got this, so if this is your work, please contact me so I can give proper credit.)

The only similarities are the first two notes, and the first eighth note of the second bar. Everything else is different.

Back to Dan Bogosian:

"Got To Give It Up" opens with a melodic run that spans the same musical distance as the entire Thicke song. It's actually a perfect vehicle to show off Gaye's voice; the run is challenging by itself, and he routinely jumps up and down four scale notes — no easy feat for an untrained vocalist. "Blurred Lines" is the opposite: the reason everyone seems to be able to sing along with Thicke…[is] that they're sung entirely within the first five notes of the major scale (i.e. the pentascale)."[ref]A Music Theory Expert Explains Why the "Blurred Lines" Copyright Decision Is Wrong[/ref]

"To put it in more digestible terms: Thicke's vocal performance is comparable to Ringo Starr's in "Yellow Submarine," and Marvin Gaye was one of soul music's greatest talents because of vocal parts like "Got To Give It Up."[ref]Id.[/ref]

"Throwing aside that Marvin Gaye's song is nearly three times as long as "Blurred Lines," it's still obvious that the melodies, harmonies, chord progressions, and rhythms are different."[ref]Id.[/ref]

Remember the test for infringement is "substantial similarity" not just similarity. What does substantial similarity look and sound like? Here is a very recent example; Tom Petty and the Heartbreaker's "I Won't Back Down" and Sam Smith's "Stay With Me" (which, by the way, won a Grammy as Song of the Year,[ref]Stay with Me (Sam Smith song)[/ref] an award given to the songwriter. Oops). After adjusting for pitch and tempo, this mash-up shows that the two songs can be sung right over each other, and the choruses are nearly identical.

https://youtu.be/qkcZV97O3pw

Here is a transcription of the two competing songs in the "How Deep Is Your Love" case. (I have forgotten where I got this, so if this is your work, please contact me so I can give proper credit.)

Look at the first three bars of music. Out of the eight notes played, six are the exact same pitch, and the timing of all the notes is identical. All counted, there are 30 instances of notes sharing the same pitch and time value. It is worth mentioning that this jury also ruled against the Bee Gees, a finding later reversed for lack of proof of access by the Bee Gees.

In the GTGIU case, both sides presented dueling expert witnesses as to the infringement or non-infringement of GTGIU. Judith Finell was the expert for the Gaye estate.

"She found the similarities in their melodies ‘pretty stunning' and ‘highly unusual,' she testified. She said both begin with a repetition of the same note — ‘one of the most important considerations in comparing melodies' — and end with a single word (‘girl' and ‘dancing') sung over several notes, the effect called a melisma, among other likenesses."[ref]How Similar Is 'Blurred Lines' To A 1977 Marvin Gaye Hit?[/ref]

The fact that both songs repeat the first note is "'one of the most important considerations in comparing melodies'? Perhaps, but musically it's also one of the easiest things to do. Most of her remaining testimony regaled the jury with points which are in my mind, so picky as to be almost irrelevant, such as:

"'In the case of these two hooks, the key words of the hook, the money words — 'good girl' and 'dancing' — come immediately after the bar line,' said Finell, referring to the timing of the words."[ref]Id.[/ref]

Really? This is evidence of substantial similarity? I'm not buying it.

"The phrases share three of their four notes, she said."[ref]Id.[/ref] Well, now you've got something, but you have to examine the rest of the song as well, not just four notes. It's substantial similarity, not just similarity.

So where did the Williams/Thicke camp go wrong? I think that Robin Thicke was hamstrung by his own press interviews in which he admitted that GTGIU was the template for writing BL.[ref]Marvin Gaye's heirs win $7.4 million for 'Blurred Lines' plagiarism[/ref] His attempts to backtrack from these statements at trial obviously made it worse and set the jury on a course against him. As I have noted before on this blog, juries take a very dim view of perjury, and they tend to slam the perceived perjurer accordingly.

So where does the Williams/Thicke team go from here? Well, naturally, their lawyer has announced the inevitable appeal[ref]Robin Thicke and Pharrell's Lawyer to Appeal 'Blurred Lines' Verdict[/ref] as well as a flurry of post-trial motions.[ref]Pharrell Williams' Lawyer: "We're Entering the Bottom of the Sixth Inning" (Guest Column)[/ref] The first is likely to ask the Judge for a "Judgment Notwithstanding the Verdict," or Judgment N.O.V. Basically, this motion asks the Judge to rule for their side, and toss out the juries' verdict. There, they will argue:

• "On the merits, there was no properly‑admissible evidence upon which the jury could have found copying. A comparison of the two songs readily reveals that there isn't one note in the melody that's the same, there isn't one chord in the entire song that's the same, and there are no more than three notes in the bass lines, out of twenty six notes, that are the same."[ref]Id.[/ref]

• "While the judge correctly ruled that only the sheet music deposited with the copyright office was at issue, the Gaye's musicologist improperly testified as to several alleged similarities between the two songs that are not reflected in that sheet music."[ref]Id.[/ref]

• The Gaye family "musicologist testified that the lyrics were significantly similar, even though there aren't two words in common."[ref]Id.[/ref]

• [T]he jury was not permitted to learn that the Gayes consulted with at least two prominent musicologists who declined to give an opinion that the songs were substantially similar before finding musicologist Judith Finell to provide the opinion they needed.[ref]Id.[/ref]

This is a tough one to win. Basically, you're going to have to convince the Judge that he should not have admitted evidence that he already deemed admissible, and that no jury in their right mind could find a case of infringement, when this jury did just that.

Then there's the appeal. Along with the points raised above, the jury's answers to questions in the verdict also might be mined for appellate fodder. The jury found responsibility for the infringement on William and Thicke, but no one else. So far so good. When asked the question, was the infringement of Williams and Thicke "innocent," they answered "no." So the infringement was willful then, right? Again, the jury says "no." So if the infringement was not innocent, and not willful, then what was it? Accidental? The Williams/Thicke side has all admitted they knew the song well and were attempting to emulate its "vibe." A very curious verdict indeed.

As to what this all means for the future of music? Not much, really. Jury verdicts have very little precedential value, and findings of infringement tend to be rare and fact specific. Consider that performing rights society ASCAP claims to represent 525,000 composers,[ref]About ASCAP[/ref] and while I was unable to get a fix on the number of songs administered by ASCAP, the last figure I read put it around 7 million songs. Notable successful copyright infringement claims number but a handful. This is because most copyright claims fail on the question of access, that is, the composer had to have heard the song in order to copy it. This is why the Bee Gees ultimately prevailed, despite the very similar nature of the songs in question. It also proves that two songs can be composed in isolation of each other, and yet be substantially similar.

This is not the case with "My Sweet Lord," "Stay With Me" and "Blurred Lines." In each case, the complaining party had a hit song that makes access a foregone conclusion, or at least very hard to deny.[ref]Tom Petty on Sam Smith Settlement: 'No Hard Feelings. These Things Happen'[/ref]

Two final notes. Attorneys for the Gaye estate say they will seek an injunction against further distribution of BL.[ref]Living in Blurred Times[/ref] This does not make sense. Why stop distribution of the most popular song of last year? It would be better to file a motion to require the record companies pay all the subsequent royalties over to the Estate, one would think.

Also, the attorney for Williams and Thicke is quick to say "[L]et me disabuse the world of the notion that our clients started this confrontation. A declaratory relief lawsuit was filed by our clients only after the Gaye family threatened to bring their own copyright infringement claim when discussions broke down in the face of the Gaye's demand that they be given 100% ownership of ‘Blurred Lines.'"[ref]Pharrell Williams' Lawyer: "We're Entering the Bottom of the Sixth Inning" (Guest Column)[/ref] Well, except that you did file the suit first, bringing the dispute to a head. Yes, because of the Supreme Court ruling in the Raging Bull case, the three year statute of limitations would never run out,[ref]Taking the Raging Bull by the Horns: A Statute of Limitations That Never Expires?[/ref] but if the Gaye Estate waited long enough, they would only be able to claim damages for the three year period immediately preceding the filing, and therefore possibly limit the amount of damages they could request.

Right now, it's winner take all. And if I were Robin Thicke's attorney, I'd tell him to shut up.

Look at the first three bars of music. Out of the eight notes played, six are the exact same pitch, and the timing of all the notes is identical. All counted, there are 30 instances of notes sharing the same pitch and time value. It is worth mentioning that this jury also ruled against the Bee Gees, a finding later reversed for lack of proof of access by the Bee Gees.

In the GTGIU case, both sides presented dueling expert witnesses as to the infringement or non-infringement of GTGIU. Judith Finell was the expert for the Gaye estate.

"She found the similarities in their melodies ‘pretty stunning' and ‘highly unusual,' she testified. She said both begin with a repetition of the same note — ‘one of the most important considerations in comparing melodies' — and end with a single word (‘girl' and ‘dancing') sung over several notes, the effect called a melisma, among other likenesses."[ref]How Similar Is 'Blurred Lines' To A 1977 Marvin Gaye Hit?[/ref]

The fact that both songs repeat the first note is "'one of the most important considerations in comparing melodies'? Perhaps, but musically it's also one of the easiest things to do. Most of her remaining testimony regaled the jury with points which are in my mind, so picky as to be almost irrelevant, such as:

"'In the case of these two hooks, the key words of the hook, the money words — 'good girl' and 'dancing' — come immediately after the bar line,' said Finell, referring to the timing of the words."[ref]Id.[/ref]

Really? This is evidence of substantial similarity? I'm not buying it.

"The phrases share three of their four notes, she said."[ref]Id.[/ref] Well, now you've got something, but you have to examine the rest of the song as well, not just four notes. It's substantial similarity, not just similarity.

So where did the Williams/Thicke camp go wrong? I think that Robin Thicke was hamstrung by his own press interviews in which he admitted that GTGIU was the template for writing BL.[ref]Marvin Gaye's heirs win $7.4 million for 'Blurred Lines' plagiarism[/ref] His attempts to backtrack from these statements at trial obviously made it worse and set the jury on a course against him. As I have noted before on this blog, juries take a very dim view of perjury, and they tend to slam the perceived perjurer accordingly.

So where does the Williams/Thicke team go from here? Well, naturally, their lawyer has announced the inevitable appeal[ref]Robin Thicke and Pharrell's Lawyer to Appeal 'Blurred Lines' Verdict[/ref] as well as a flurry of post-trial motions.[ref]Pharrell Williams' Lawyer: "We're Entering the Bottom of the Sixth Inning" (Guest Column)[/ref] The first is likely to ask the Judge for a "Judgment Notwithstanding the Verdict," or Judgment N.O.V. Basically, this motion asks the Judge to rule for their side, and toss out the juries' verdict. There, they will argue:

• "On the merits, there was no properly‑admissible evidence upon which the jury could have found copying. A comparison of the two songs readily reveals that there isn't one note in the melody that's the same, there isn't one chord in the entire song that's the same, and there are no more than three notes in the bass lines, out of twenty six notes, that are the same."[ref]Id.[/ref]

• "While the judge correctly ruled that only the sheet music deposited with the copyright office was at issue, the Gaye's musicologist improperly testified as to several alleged similarities between the two songs that are not reflected in that sheet music."[ref]Id.[/ref]

• The Gaye family "musicologist testified that the lyrics were significantly similar, even though there aren't two words in common."[ref]Id.[/ref]

• [T]he jury was not permitted to learn that the Gayes consulted with at least two prominent musicologists who declined to give an opinion that the songs were substantially similar before finding musicologist Judith Finell to provide the opinion they needed.[ref]Id.[/ref]

This is a tough one to win. Basically, you're going to have to convince the Judge that he should not have admitted evidence that he already deemed admissible, and that no jury in their right mind could find a case of infringement, when this jury did just that.

Then there's the appeal. Along with the points raised above, the jury's answers to questions in the verdict also might be mined for appellate fodder. The jury found responsibility for the infringement on William and Thicke, but no one else. So far so good. When asked the question, was the infringement of Williams and Thicke "innocent," they answered "no." So the infringement was willful then, right? Again, the jury says "no." So if the infringement was not innocent, and not willful, then what was it? Accidental? The Williams/Thicke side has all admitted they knew the song well and were attempting to emulate its "vibe." A very curious verdict indeed.

As to what this all means for the future of music? Not much, really. Jury verdicts have very little precedential value, and findings of infringement tend to be rare and fact specific. Consider that performing rights society ASCAP claims to represent 525,000 composers,[ref]About ASCAP[/ref] and while I was unable to get a fix on the number of songs administered by ASCAP, the last figure I read put it around 7 million songs. Notable successful copyright infringement claims number but a handful. This is because most copyright claims fail on the question of access, that is, the composer had to have heard the song in order to copy it. This is why the Bee Gees ultimately prevailed, despite the very similar nature of the songs in question. It also proves that two songs can be composed in isolation of each other, and yet be substantially similar.

This is not the case with "My Sweet Lord," "Stay With Me" and "Blurred Lines." In each case, the complaining party had a hit song that makes access a foregone conclusion, or at least very hard to deny.[ref]Tom Petty on Sam Smith Settlement: 'No Hard Feelings. These Things Happen'[/ref]

Two final notes. Attorneys for the Gaye estate say they will seek an injunction against further distribution of BL.[ref]Living in Blurred Times[/ref] This does not make sense. Why stop distribution of the most popular song of last year? It would be better to file a motion to require the record companies pay all the subsequent royalties over to the Estate, one would think.

Also, the attorney for Williams and Thicke is quick to say "[L]et me disabuse the world of the notion that our clients started this confrontation. A declaratory relief lawsuit was filed by our clients only after the Gaye family threatened to bring their own copyright infringement claim when discussions broke down in the face of the Gaye's demand that they be given 100% ownership of ‘Blurred Lines.'"[ref]Pharrell Williams' Lawyer: "We're Entering the Bottom of the Sixth Inning" (Guest Column)[/ref] Well, except that you did file the suit first, bringing the dispute to a head. Yes, because of the Supreme Court ruling in the Raging Bull case, the three year statute of limitations would never run out,[ref]Taking the Raging Bull by the Horns: A Statute of Limitations That Never Expires?[/ref] but if the Gaye Estate waited long enough, they would only be able to claim damages for the three year period immediately preceding the filing, and therefore possibly limit the amount of damages they could request.

Right now, it's winner take all. And if I were Robin Thicke's attorney, I'd tell him to shut up.

This is the bass line from "Got to Give It Up." For those of you who do not read music I have notated it for you.

This is the bass line for "Blurred Lines."

This is the bass line for "Blurred Lines."

I just don't hear it, and I certainly don't see it. The GTGIU bass line runs for 11 bars, while the BL repeats on an eight bar cycle. The BL bass line is far more sparse and repetitious, and the octave jumping flourish at the end has been a staple of funk/disco music for at least 40 years, maybe more.

Then there is the chord progression, or lack thereof. BL is basically what musicians call a "vamp," a cycle of repeated chords that does not change. This chart comes courtesy of the LA Times newspaper,[ref]'Blurred Lines' vs. 'Got to Give It Up'[/ref] and shows that the phrasing of the chords is very dissimilar.

Music theory graduate Dan Bogosian put it like this:

"There are literally only two chords in "Blurred Lines;" a lot of people have inappropriately labeled it G to D, but it's actually C/G to D. That's one of the gratifying things about the song: because the C chord doesn't have a C in the bass, it maintains tension throughout… the genius of Williams and Thicke has the bass doing one thing, and everything else doing another."[ref]A Music Theory Expert Explains Why the "Blurred Lines" Copyright Decision Is Wrong[/ref]

"This progression is known as IV to V, and it's one of the most common set of harmonies in all of music; it happens in every single doo-wop song, and in roughly half of all pop songs and classical compositions. A bass line that never hits the root or truly resolves is unusual nowadays, but it's actually the defining trait that makes the opening moment of "Blurred Lines" funky."[ref]Id.[/ref]

"On the other hand, "Got to Give it Up" has twice as many chords as Thicke's (four versus two), and includes the IV to V chord progression on every repeat. Each repeat resolves, never using the strange tension in the bass the way "Blurred Lines" does."[ref]Id.[/ref]

Another allegation is that Gaye's "distinctive cow bell" rhythm was borrowed.[ref]Did Robin Thicke steal 'Blurred Lines' from Marvin Gaye?[/ref] Back to musicologist Joe Bennet, who prepared these charts:

Here is the cowbell part from GTGIU:

I just don't hear it, and I certainly don't see it. The GTGIU bass line runs for 11 bars, while the BL repeats on an eight bar cycle. The BL bass line is far more sparse and repetitious, and the octave jumping flourish at the end has been a staple of funk/disco music for at least 40 years, maybe more.

Then there is the chord progression, or lack thereof. BL is basically what musicians call a "vamp," a cycle of repeated chords that does not change. This chart comes courtesy of the LA Times newspaper,[ref]'Blurred Lines' vs. 'Got to Give It Up'[/ref] and shows that the phrasing of the chords is very dissimilar.

Music theory graduate Dan Bogosian put it like this:

"There are literally only two chords in "Blurred Lines;" a lot of people have inappropriately labeled it G to D, but it's actually C/G to D. That's one of the gratifying things about the song: because the C chord doesn't have a C in the bass, it maintains tension throughout… the genius of Williams and Thicke has the bass doing one thing, and everything else doing another."[ref]A Music Theory Expert Explains Why the "Blurred Lines" Copyright Decision Is Wrong[/ref]

"This progression is known as IV to V, and it's one of the most common set of harmonies in all of music; it happens in every single doo-wop song, and in roughly half of all pop songs and classical compositions. A bass line that never hits the root or truly resolves is unusual nowadays, but it's actually the defining trait that makes the opening moment of "Blurred Lines" funky."[ref]Id.[/ref]

"On the other hand, "Got to Give it Up" has twice as many chords as Thicke's (four versus two), and includes the IV to V chord progression on every repeat. Each repeat resolves, never using the strange tension in the bass the way "Blurred Lines" does."[ref]Id.[/ref]

Another allegation is that Gaye's "distinctive cow bell" rhythm was borrowed.[ref]Did Robin Thicke steal 'Blurred Lines' from Marvin Gaye?[/ref] Back to musicologist Joe Bennet, who prepared these charts:

Here is the cowbell part from GTGIU:

Bennet says there are actually two cowbell parts in BL. He transcribes them as follows:[ref]Id.[/ref]

Bennet says there are actually two cowbell parts in BL. He transcribes them as follows:[ref]Id.[/ref]

The only similarities are the first two notes, and the first eighth note of the second bar. Everything else is different.

Back to Dan Bogosian:

"Got To Give It Up" opens with a melodic run that spans the same musical distance as the entire Thicke song. It's actually a perfect vehicle to show off Gaye's voice; the run is challenging by itself, and he routinely jumps up and down four scale notes — no easy feat for an untrained vocalist. "Blurred Lines" is the opposite: the reason everyone seems to be able to sing along with Thicke…[is] that they're sung entirely within the first five notes of the major scale (i.e. the pentascale)."[ref]A Music Theory Expert Explains Why the "Blurred Lines" Copyright Decision Is Wrong[/ref]

"To put it in more digestible terms: Thicke's vocal performance is comparable to Ringo Starr's in "Yellow Submarine," and Marvin Gaye was one of soul music's greatest talents because of vocal parts like "Got To Give It Up."[ref]Id.[/ref]

"Throwing aside that Marvin Gaye's song is nearly three times as long as "Blurred Lines," it's still obvious that the melodies, harmonies, chord progressions, and rhythms are different."[ref]Id.[/ref]

Remember the test for infringement is "substantial similarity" not just similarity. What does substantial similarity look and sound like? Here is a very recent example; Tom Petty and the Heartbreaker's "I Won't Back Down" and Sam Smith's "Stay With Me" (which, by the way, won a Grammy as Song of the Year,[ref]Stay with Me (Sam Smith song)[/ref] an award given to the songwriter. Oops). After adjusting for pitch and tempo, this mash-up shows that the two songs can be sung right over each other, and the choruses are nearly identical.

https://youtu.be/qkcZV97O3pw

Here is a transcription of the two competing songs in the "How Deep Is Your Love" case. (I have forgotten where I got this, so if this is your work, please contact me so I can give proper credit.)

The only similarities are the first two notes, and the first eighth note of the second bar. Everything else is different.

Back to Dan Bogosian:

"Got To Give It Up" opens with a melodic run that spans the same musical distance as the entire Thicke song. It's actually a perfect vehicle to show off Gaye's voice; the run is challenging by itself, and he routinely jumps up and down four scale notes — no easy feat for an untrained vocalist. "Blurred Lines" is the opposite: the reason everyone seems to be able to sing along with Thicke…[is] that they're sung entirely within the first five notes of the major scale (i.e. the pentascale)."[ref]A Music Theory Expert Explains Why the "Blurred Lines" Copyright Decision Is Wrong[/ref]

"To put it in more digestible terms: Thicke's vocal performance is comparable to Ringo Starr's in "Yellow Submarine," and Marvin Gaye was one of soul music's greatest talents because of vocal parts like "Got To Give It Up."[ref]Id.[/ref]

"Throwing aside that Marvin Gaye's song is nearly three times as long as "Blurred Lines," it's still obvious that the melodies, harmonies, chord progressions, and rhythms are different."[ref]Id.[/ref]

Remember the test for infringement is "substantial similarity" not just similarity. What does substantial similarity look and sound like? Here is a very recent example; Tom Petty and the Heartbreaker's "I Won't Back Down" and Sam Smith's "Stay With Me" (which, by the way, won a Grammy as Song of the Year,[ref]Stay with Me (Sam Smith song)[/ref] an award given to the songwriter. Oops). After adjusting for pitch and tempo, this mash-up shows that the two songs can be sung right over each other, and the choruses are nearly identical.

https://youtu.be/qkcZV97O3pw

Here is a transcription of the two competing songs in the "How Deep Is Your Love" case. (I have forgotten where I got this, so if this is your work, please contact me so I can give proper credit.)

Look at the first three bars of music. Out of the eight notes played, six are the exact same pitch, and the timing of all the notes is identical. All counted, there are 30 instances of notes sharing the same pitch and time value. It is worth mentioning that this jury also ruled against the Bee Gees, a finding later reversed for lack of proof of access by the Bee Gees.

In the GTGIU case, both sides presented dueling expert witnesses as to the infringement or non-infringement of GTGIU. Judith Finell was the expert for the Gaye estate.

"She found the similarities in their melodies ‘pretty stunning' and ‘highly unusual,' she testified. She said both begin with a repetition of the same note — ‘one of the most important considerations in comparing melodies' — and end with a single word (‘girl' and ‘dancing') sung over several notes, the effect called a melisma, among other likenesses."[ref]How Similar Is 'Blurred Lines' To A 1977 Marvin Gaye Hit?[/ref]

The fact that both songs repeat the first note is "'one of the most important considerations in comparing melodies'? Perhaps, but musically it's also one of the easiest things to do. Most of her remaining testimony regaled the jury with points which are in my mind, so picky as to be almost irrelevant, such as:

"'In the case of these two hooks, the key words of the hook, the money words — 'good girl' and 'dancing' — come immediately after the bar line,' said Finell, referring to the timing of the words."[ref]Id.[/ref]

Really? This is evidence of substantial similarity? I'm not buying it.

"The phrases share three of their four notes, she said."[ref]Id.[/ref] Well, now you've got something, but you have to examine the rest of the song as well, not just four notes. It's substantial similarity, not just similarity.

So where did the Williams/Thicke camp go wrong? I think that Robin Thicke was hamstrung by his own press interviews in which he admitted that GTGIU was the template for writing BL.[ref]Marvin Gaye's heirs win $7.4 million for 'Blurred Lines' plagiarism[/ref] His attempts to backtrack from these statements at trial obviously made it worse and set the jury on a course against him. As I have noted before on this blog, juries take a very dim view of perjury, and they tend to slam the perceived perjurer accordingly.

So where does the Williams/Thicke team go from here? Well, naturally, their lawyer has announced the inevitable appeal[ref]Robin Thicke and Pharrell's Lawyer to Appeal 'Blurred Lines' Verdict[/ref] as well as a flurry of post-trial motions.[ref]Pharrell Williams' Lawyer: "We're Entering the Bottom of the Sixth Inning" (Guest Column)[/ref] The first is likely to ask the Judge for a "Judgment Notwithstanding the Verdict," or Judgment N.O.V. Basically, this motion asks the Judge to rule for their side, and toss out the juries' verdict. There, they will argue:

• "On the merits, there was no properly‑admissible evidence upon which the jury could have found copying. A comparison of the two songs readily reveals that there isn't one note in the melody that's the same, there isn't one chord in the entire song that's the same, and there are no more than three notes in the bass lines, out of twenty six notes, that are the same."[ref]Id.[/ref]

• "While the judge correctly ruled that only the sheet music deposited with the copyright office was at issue, the Gaye's musicologist improperly testified as to several alleged similarities between the two songs that are not reflected in that sheet music."[ref]Id.[/ref]

• The Gaye family "musicologist testified that the lyrics were significantly similar, even though there aren't two words in common."[ref]Id.[/ref]

• [T]he jury was not permitted to learn that the Gayes consulted with at least two prominent musicologists who declined to give an opinion that the songs were substantially similar before finding musicologist Judith Finell to provide the opinion they needed.[ref]Id.[/ref]

This is a tough one to win. Basically, you're going to have to convince the Judge that he should not have admitted evidence that he already deemed admissible, and that no jury in their right mind could find a case of infringement, when this jury did just that.

Then there's the appeal. Along with the points raised above, the jury's answers to questions in the verdict also might be mined for appellate fodder. The jury found responsibility for the infringement on William and Thicke, but no one else. So far so good. When asked the question, was the infringement of Williams and Thicke "innocent," they answered "no." So the infringement was willful then, right? Again, the jury says "no." So if the infringement was not innocent, and not willful, then what was it? Accidental? The Williams/Thicke side has all admitted they knew the song well and were attempting to emulate its "vibe." A very curious verdict indeed.

As to what this all means for the future of music? Not much, really. Jury verdicts have very little precedential value, and findings of infringement tend to be rare and fact specific. Consider that performing rights society ASCAP claims to represent 525,000 composers,[ref]About ASCAP[/ref] and while I was unable to get a fix on the number of songs administered by ASCAP, the last figure I read put it around 7 million songs. Notable successful copyright infringement claims number but a handful. This is because most copyright claims fail on the question of access, that is, the composer had to have heard the song in order to copy it. This is why the Bee Gees ultimately prevailed, despite the very similar nature of the songs in question. It also proves that two songs can be composed in isolation of each other, and yet be substantially similar.

This is not the case with "My Sweet Lord," "Stay With Me" and "Blurred Lines." In each case, the complaining party had a hit song that makes access a foregone conclusion, or at least very hard to deny.[ref]Tom Petty on Sam Smith Settlement: 'No Hard Feelings. These Things Happen'[/ref]

Two final notes. Attorneys for the Gaye estate say they will seek an injunction against further distribution of BL.[ref]Living in Blurred Times[/ref] This does not make sense. Why stop distribution of the most popular song of last year? It would be better to file a motion to require the record companies pay all the subsequent royalties over to the Estate, one would think.

Also, the attorney for Williams and Thicke is quick to say "[L]et me disabuse the world of the notion that our clients started this confrontation. A declaratory relief lawsuit was filed by our clients only after the Gaye family threatened to bring their own copyright infringement claim when discussions broke down in the face of the Gaye's demand that they be given 100% ownership of ‘Blurred Lines.'"[ref]Pharrell Williams' Lawyer: "We're Entering the Bottom of the Sixth Inning" (Guest Column)[/ref] Well, except that you did file the suit first, bringing the dispute to a head. Yes, because of the Supreme Court ruling in the Raging Bull case, the three year statute of limitations would never run out,[ref]Taking the Raging Bull by the Horns: A Statute of Limitations That Never Expires?[/ref] but if the Gaye Estate waited long enough, they would only be able to claim damages for the three year period immediately preceding the filing, and therefore possibly limit the amount of damages they could request.

Right now, it's winner take all. And if I were Robin Thicke's attorney, I'd tell him to shut up.

Look at the first three bars of music. Out of the eight notes played, six are the exact same pitch, and the timing of all the notes is identical. All counted, there are 30 instances of notes sharing the same pitch and time value. It is worth mentioning that this jury also ruled against the Bee Gees, a finding later reversed for lack of proof of access by the Bee Gees.

In the GTGIU case, both sides presented dueling expert witnesses as to the infringement or non-infringement of GTGIU. Judith Finell was the expert for the Gaye estate.

"She found the similarities in their melodies ‘pretty stunning' and ‘highly unusual,' she testified. She said both begin with a repetition of the same note — ‘one of the most important considerations in comparing melodies' — and end with a single word (‘girl' and ‘dancing') sung over several notes, the effect called a melisma, among other likenesses."[ref]How Similar Is 'Blurred Lines' To A 1977 Marvin Gaye Hit?[/ref]

The fact that both songs repeat the first note is "'one of the most important considerations in comparing melodies'? Perhaps, but musically it's also one of the easiest things to do. Most of her remaining testimony regaled the jury with points which are in my mind, so picky as to be almost irrelevant, such as:

"'In the case of these two hooks, the key words of the hook, the money words — 'good girl' and 'dancing' — come immediately after the bar line,' said Finell, referring to the timing of the words."[ref]Id.[/ref]

Really? This is evidence of substantial similarity? I'm not buying it.

"The phrases share three of their four notes, she said."[ref]Id.[/ref] Well, now you've got something, but you have to examine the rest of the song as well, not just four notes. It's substantial similarity, not just similarity.

So where did the Williams/Thicke camp go wrong? I think that Robin Thicke was hamstrung by his own press interviews in which he admitted that GTGIU was the template for writing BL.[ref]Marvin Gaye's heirs win $7.4 million for 'Blurred Lines' plagiarism[/ref] His attempts to backtrack from these statements at trial obviously made it worse and set the jury on a course against him. As I have noted before on this blog, juries take a very dim view of perjury, and they tend to slam the perceived perjurer accordingly.

So where does the Williams/Thicke team go from here? Well, naturally, their lawyer has announced the inevitable appeal[ref]Robin Thicke and Pharrell's Lawyer to Appeal 'Blurred Lines' Verdict[/ref] as well as a flurry of post-trial motions.[ref]Pharrell Williams' Lawyer: "We're Entering the Bottom of the Sixth Inning" (Guest Column)[/ref] The first is likely to ask the Judge for a "Judgment Notwithstanding the Verdict," or Judgment N.O.V. Basically, this motion asks the Judge to rule for their side, and toss out the juries' verdict. There, they will argue:

• "On the merits, there was no properly‑admissible evidence upon which the jury could have found copying. A comparison of the two songs readily reveals that there isn't one note in the melody that's the same, there isn't one chord in the entire song that's the same, and there are no more than three notes in the bass lines, out of twenty six notes, that are the same."[ref]Id.[/ref]

• "While the judge correctly ruled that only the sheet music deposited with the copyright office was at issue, the Gaye's musicologist improperly testified as to several alleged similarities between the two songs that are not reflected in that sheet music."[ref]Id.[/ref]

• The Gaye family "musicologist testified that the lyrics were significantly similar, even though there aren't two words in common."[ref]Id.[/ref]

• [T]he jury was not permitted to learn that the Gayes consulted with at least two prominent musicologists who declined to give an opinion that the songs were substantially similar before finding musicologist Judith Finell to provide the opinion they needed.[ref]Id.[/ref]

This is a tough one to win. Basically, you're going to have to convince the Judge that he should not have admitted evidence that he already deemed admissible, and that no jury in their right mind could find a case of infringement, when this jury did just that.

Then there's the appeal. Along with the points raised above, the jury's answers to questions in the verdict also might be mined for appellate fodder. The jury found responsibility for the infringement on William and Thicke, but no one else. So far so good. When asked the question, was the infringement of Williams and Thicke "innocent," they answered "no." So the infringement was willful then, right? Again, the jury says "no." So if the infringement was not innocent, and not willful, then what was it? Accidental? The Williams/Thicke side has all admitted they knew the song well and were attempting to emulate its "vibe." A very curious verdict indeed.

As to what this all means for the future of music? Not much, really. Jury verdicts have very little precedential value, and findings of infringement tend to be rare and fact specific. Consider that performing rights society ASCAP claims to represent 525,000 composers,[ref]About ASCAP[/ref] and while I was unable to get a fix on the number of songs administered by ASCAP, the last figure I read put it around 7 million songs. Notable successful copyright infringement claims number but a handful. This is because most copyright claims fail on the question of access, that is, the composer had to have heard the song in order to copy it. This is why the Bee Gees ultimately prevailed, despite the very similar nature of the songs in question. It also proves that two songs can be composed in isolation of each other, and yet be substantially similar.

This is not the case with "My Sweet Lord," "Stay With Me" and "Blurred Lines." In each case, the complaining party had a hit song that makes access a foregone conclusion, or at least very hard to deny.[ref]Tom Petty on Sam Smith Settlement: 'No Hard Feelings. These Things Happen'[/ref]

Two final notes. Attorneys for the Gaye estate say they will seek an injunction against further distribution of BL.[ref]Living in Blurred Times[/ref] This does not make sense. Why stop distribution of the most popular song of last year? It would be better to file a motion to require the record companies pay all the subsequent royalties over to the Estate, one would think.

Also, the attorney for Williams and Thicke is quick to say "[L]et me disabuse the world of the notion that our clients started this confrontation. A declaratory relief lawsuit was filed by our clients only after the Gaye family threatened to bring their own copyright infringement claim when discussions broke down in the face of the Gaye's demand that they be given 100% ownership of ‘Blurred Lines.'"[ref]Pharrell Williams' Lawyer: "We're Entering the Bottom of the Sixth Inning" (Guest Column)[/ref] Well, except that you did file the suit first, bringing the dispute to a head. Yes, because of the Supreme Court ruling in the Raging Bull case, the three year statute of limitations would never run out,[ref]Taking the Raging Bull by the Horns: A Statute of Limitations That Never Expires?[/ref] but if the Gaye Estate waited long enough, they would only be able to claim damages for the three year period immediately preceding the filing, and therefore possibly limit the amount of damages they could request.

Right now, it's winner take all. And if I were Robin Thicke's attorney, I'd tell him to shut up.

No Subjects

Two more copyright myths bit the dust this week, though it is doubtless that they will continue to be repeated. The first is the persistent myth of the $150,000 statutory damages award. The second is the myth of the DMCA takedown notice as the enemy of free speech.

The Myth of the $150,000 Statutory Damages Award

This is one of the favorite fear-mongering tactics of the Electronic Frontier Foundation,[ref]Collateral Damages: Why Congress Needs To Fix Copyright Law's Civil Penalties[/ref] namely the ability of a Court, in extreme circumstances to award the sum of $150,000 in statutory damages for the infringement of one copyrighted work.[ref]17 USC 504(c)(2)[/ref] Yes, the statute does provide for this kind of award, but only in cases where there has been "willful" infringement of copyright. The true story is that no one gets awarded this level of statutory damages. Note that in the EFF post referenced above, it failed to cite even one instance where the maximum $150,000 award was made. As a part of my duties, a digest of all court decisions mentioning the word "copyright" is sent to my desk every morning. Having been here a little over a year, I have never seen a court award the maximum amount of statutory damages. The truth is, the awards are usually a couple of thousand dollars, and in several cases I saw, the minimum award of $750 was made. For example, in an endnote to this recent blog post, I detailed the awards made in 7 published judgments won by alleged "copyright troll" Malibu Media. The most that was awarded by any Court was $2,250 per work infringed, and twice, the award was the statutory minimum, $750 per work infringed.[ref]Copyright Blog Update: Malibu Media Finally Loses and "Transformative Use" Artist Assumes the Risks of a Lawsuit at endnote 3.[/ref] On March 10, 2015, the Senate Subcommittee on Antitrust, Competition Policy and Consumer Rights held hearings on whether the Department of Justice consent decrees with the music performing rights organizations should be modified or abolished.[ref]How Much For a Song?: The Antitrust Decrees that Govern the Market for Music[/ref] Once again, Chris Harrison, the Vice-President, Business Affairs at Pandora, trotted out the evil specter of the $150,000 damage award. Unfortunately for him, sitting on the subcommittee was Al Franken, who some of you may remember from "Saturday Night Live," but is now a Senator from Minnesota. Mr. Franken obviously knows a thing or two about show business and copyrights. Franken pressed him on how many times judgments had resulted in the maximum award of $150,000 being awarded. For his part, Harrison tried to dodge the question, but Franken would not let him. After Franken repeated his question several more times, Harrison finally admitted he knew of no such cases in which the maximum award had been made.The DMCA as the Enemy of Free Speech

Few things about copyright are more often and wrongfully asserted than the notion that copyrights in general, and the DMCA in particular, inhibits "free speech." This is reflected in Google's (and Twitter's) policy of forwarding all takedown notices to the EFF funded "Chilling Effects" organization. Landing in my inbox this week was this thoroughly researched law review article in the Virginia Journal of Law and Technology, by Daniel Seng.[ref]The State of the Discordant Union: An Empirical Analysis of DMCA Takedown Notices by Daniel Seng 18 Va. J.L. & Tech. 369 (2014) View Article[/ref] In his article, The State of the Discordant Union: An Empirical Analysis of DMCA Takedown Notices, Mr. Seng writes of how he created a program to analyze the database at Chilling Effects for the years 2008 through 2012. He then broke out the data into several fields including what types of entities sent the most takedown requests (not surprisingly, it's the record industry[ref]Id. at 392[/ref]), and for the first time, we have reliable data on how many takedown requests are met with counter-notices. Remember, that under the plain language of the DMCA, if one has been served with an untrue, or even abusive DMCA notice, one can file a counter-notice and have the material re-posted. Also remember, that according to the tech companies and the EFF, "abuse of DMCA takedown notices is a real and serious problem."[ref]Notice-and-Takedown Gets its Day in Congress[/ref] Previously, this blog looked at the available evidence and found no support for this proposition and that most of the evidence put forward in support was anecdotal.[ref]DMCA "Takedown" Notices: Why "Takedown" Should Become "Take Down and Stay Down" and Why It's Good for Everyone[/ref] So, if the big tech companies and the EFF are correct, we should see a huge number of counter-notices relative to the number of valid takedowns. The numbers show the opposite. Arguments about huge numbers of bad and abusive take-down notices are pure fantasy. Mr. Seng found that there were 68 counter-notices reported to Chilling Effects in 2011 and 82 counter-notices in 2012. No counter-notices at all were reported between 2008 and 2010.[ref]Seng. at 428-429[/ref] Contrast this with the number of notices filed. In 2011, 71,798 takedown notices were sent to the organizations that report to Chilling Effects. The very next year, 2012, that number had increased over six-fold, to 448,138.[ref]Seng at table 1[/ref] Also consider that just two years later, Google alone received 345 million takedown notices.[ref]Google Asked to Remove 345 Million "Pirate" Links in 2014[/ref] To recap, in 2011, 71,798 takedown notices were reported against 68 counter-notices, making the rate of bad takedown requests 0.001% of all notices filed. In 2012, 448,138 takedown notices were reported against 82 counter-notices, making the rate of bad takedown requests 0.0002%. So, the number of takedown requests went up six times the previous year's number and the rate of bad takedowns dropped. So, as I said at the top of the post, I do not expect that these two persistent myths will go away. I expect that they will continue to be repeated, despite the fact that all available evidence points to them being not true.

No Subjects

Two notable items hit the news last week. The first was an excellent and thoroughly researched law review article by Brandy Robinson which appeared in the latest issue of the Rutgers Law Record.[ref]IP Piracy & Developing Nations: A Recipe For Terrorism Funding[/ref] (Click on the endnote to go directly to the article). The article relates in great detail how terrorist groups, and those who support them, use copyright piracy as an easy way of funding their activities. The second item was Google suddenly making public what they had refused to do before, namely, to state how many videos were removed from YouTube for content violations.

Brandy Robinson's article makes very plain that terrorist organizations use copyright infringement as a method of easily and quickly generating funds, and have been doing so for quite some time.

"[T]errorist groups, especially those in developing nations, thrive on IP piracy allowing for the successful funding of terrorist opportunities. (Footnote omitted.) Terrorist groups gravitate towards IP piracy for funding because detection of IP piracy is easily evaded and developing nations do not thoroughly understand it. (Footnote omitted.)"[ref]Id. at 42[/ref]

Amongst her points:

- International authorities found that Al Qaeda training materials suggested using counterfeit goods and materials to fund its cell activities.[ref]Id. at 51[/ref]

- British detectives claim that Pakistani DVDs account for 40% of anti-piracy confiscations in the UK, and that profits from pirated versions of Love Actually and Master and Commander funnel back to the coffers of Pakistan-based Al Qaeda operatives.[ref]Id. at page 50 footnote 75, citing Kavita Philip, What is a technological author? The pirate function and intellectual property, 8, No. 2, The Institute of Postcolonial Studies 199-218 (2005).[/ref]

- The U.S. Department of Justice found that terrorist groups are using technology to commit various kinds of crimes traditionally associated with organized criminal organizations. This includes fraud, computer-related crimes, racketeering, and the creation of so-called "bootleg," counterfeit, or illegal copies of movies, music and even software.[ref]Id. at 50[/ref]

- In 1994, the terrorist group, Hezbollah, used the illicit counterfeiting industry to fund its bombing of the Jewish Community Center (AMIA) in Buenos Aires.[ref]Id. at 53[/ref]

- In the aftermath of the 2008 London bombings, authorities identified Mohammad Sidique Khan, a bootleg CDs and DVDs dealer in South Africa, as one of the coordinators of the bombings.[ref]Id. at 49[/ref]

- Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay (a tri-border area) serve as a regional hub for terrorist organizational funding for groups such as Hezbollah and Hamas. This fundraising includes counterfeit American goods, including Microsoft software.[ref]Id. at 62[/ref] Twenty million dollars were donated to Hezbollah on an annual basis from this tri-border area resulting from illegal IP activities.[ref]Id.[/ref]

- There was a $2.5 million transfer from a DVD pirate Assad Ahmad Barakat to Hezbollah, who received a "thank you" note from the leader of Hezbollah.[ref]Id. at 63[/ref]

No Subjects