Flo and Eddies' winning streak against Sirius XM ended on June 22, 2015 when Florida District Court Judge Darrin P. Gayles ruled that "Florida common law does not provide Flo & Eddie with an exclusive right in public performance" and granted Sirius XM's Motion for Summary Judgment.[ref]Flo & Eddie, Inc. v. Sirius XM Radio, Inc. 2015 WL 3852692 District Court for the Southern District of Florida, 2015[/ref]

Faithful readers of this blog will remember that Flo and Eddie had prevailed against Sirius XM both in California[ref]Flo and Eddie v. Sirius XM Radio: Have Two Hippies from the 60's Just Changed the Course of Broadcast Music?[/ref] and in New York.[ref]Blog Update: Sirius XM Loses in New York, Fires Lawyers, Loses Again[/ref] The RIAA also won a similar suit against Sirius XM in California.[ref]Streaming Hits a Dam: Taylor Swift Says "Not So Fast," Sirius XM Loses Again and Flo and Eddie Sue Pandora[/ref] So how did the Judge in Florida rule contrary to three other Courts on what basically is the same set of facts? The problem lies with the vagaries of what the courts call "the common law."

The common law is derived from the decisions of courts over a period of time, and is not written down in easy to find sections like statutes are. The problem for Flo and Eddie was that no Florida Court had ever squarely addressed the issue. There is no Federal common law. I noted previously that this problem would be a serious burden for Flo and Eddie to overcome. As I stated in my prior blog post:

"Flo & Eddie, as Plaintiffs, bear the burden of proof to show that Florida common law copyright extends to such performances. There is no such proof, but only because it does not appear that any Florida Court has ever considered the question."

That lack of consideration proved fatal to Flo and Eddies' case. While at least one Federal Court had ruled that Florida did recognize common law copyrights in sound recordings,[ref]CBS v. Garrod, 622 F.Supp 532 US District Court for the Middle District of Florida 1985[/ref] there was never any decision on whether common law copyright in a sound recording extended to the public performance of that sound recording. The Judge here, noted that California had a specific statute in place, and that New York had several court decisions discussing the issue. The Judge in Florida, however, found that neither of these factors was present in Florida, and declined to be the first to say so, stating that "whether copyright protection for pre-1972 sound recordings should include the exclusive right of public performance is for the Florida legislature."[ref]Flo & Eddie, Inc. v. Sirius XM Radio, Inc. 2015 WL 3852692 (at page 5 of original opinion)[/ref]

If there was any error in the court's decision, it would be the finding that "Florida common law does not provide Flo & Eddie with an exclusive right in public performance."[ref]Id.[/ref] The problem with this ruling is that if the theory advanced by Flo and Eddie lacked proof to support it, the opposite is not necessarily true. In other words, if there is no evidence that any Florida court has ever considered the issue, then there is no evidence to support a finding that there is, or is not, a public performance right in pre-1972 sound recordings. The result is the same, Flo and Eddie lose. But, the reason they lose is that Flo and Eddie, as plaintiffs have the burden of proof and they have failed to provide that proof.

Also, a little puzzling since the Judge had already decided the case and did not need to address the issue, he took the time to rule that any attempt by the Florida Legislature to provide performance rights for pre-1972 sound recordings would not violate the dormant commerce clause of the U.S. Constitution, an argument made unsuccessfully by Sirius XM in the other court proceedings as well as here.

An appeal of this ruling is inevitable, and in the past, the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals has sought the guidance of the Florida Supreme Court on what the laws of the State of Florida provide. This makes sense here, because a Federal Court can only have an opinion on what they think Florida laws mandate, while the Florida Supreme Court is the final arbiter on the question of what is the law of the State of Florida and what is not the law. This case is certainly one that could benefit from their input.

So what is the ultimate effect to Sirius XM? According to the Judge here, "[d]ue to Sirius' licenses with the Federal Communications Commission and technological restraints on its satellite delivery systems, Sirius broadcasts identical programming to its subscribers in every state in the continental United States."[ref]Id. at page 1[/ref] If this is correct, then Sirius will have to win reversals in all of the three cases which they have lost, two in California and one in New York, in order to continue to play pre-1972 sound recordings. A negative outcome in any one of them would mean an effective ban on pre-1972 recordings across the United States since they have no ability to tailor the programming to an individual state.

Against odds like that, Sirius may wish to try to settle the cases before the damages pile up to a number that they cannot afford.

It's no secret that the Electronic Frontier Foundation is no friend of copyright. What is more brazen is their operation of a website that actively assists people in finding infringing copies of copyrighted works. That website is chillingeffects.org, which the EFF operates in conjunction with Harvard University's Berkman Center for Internet & Society.[ref]Chilling Effects: About Us[/ref]

Supposedly, Chilling Effects

"...is an independent 3rd party research project studying cease and desist letters concerning online content. We collect and analyze complaints about online activity, especially requests to remove content from online. Our goals are to educate the public, to facilitate research about the different kinds of complaints and requests for removal--both legitimate and questionable--that are being sent to Internet publishers and service providers, and to provide as much transparency as possible about the "ecology" of such notices, in terms of who is sending them and why, and to what effect."[ref]Chilling Effects: About Us[/ref]

What it really constitutes is the world's largest database on where to find pirated material. Here's how easy it is.

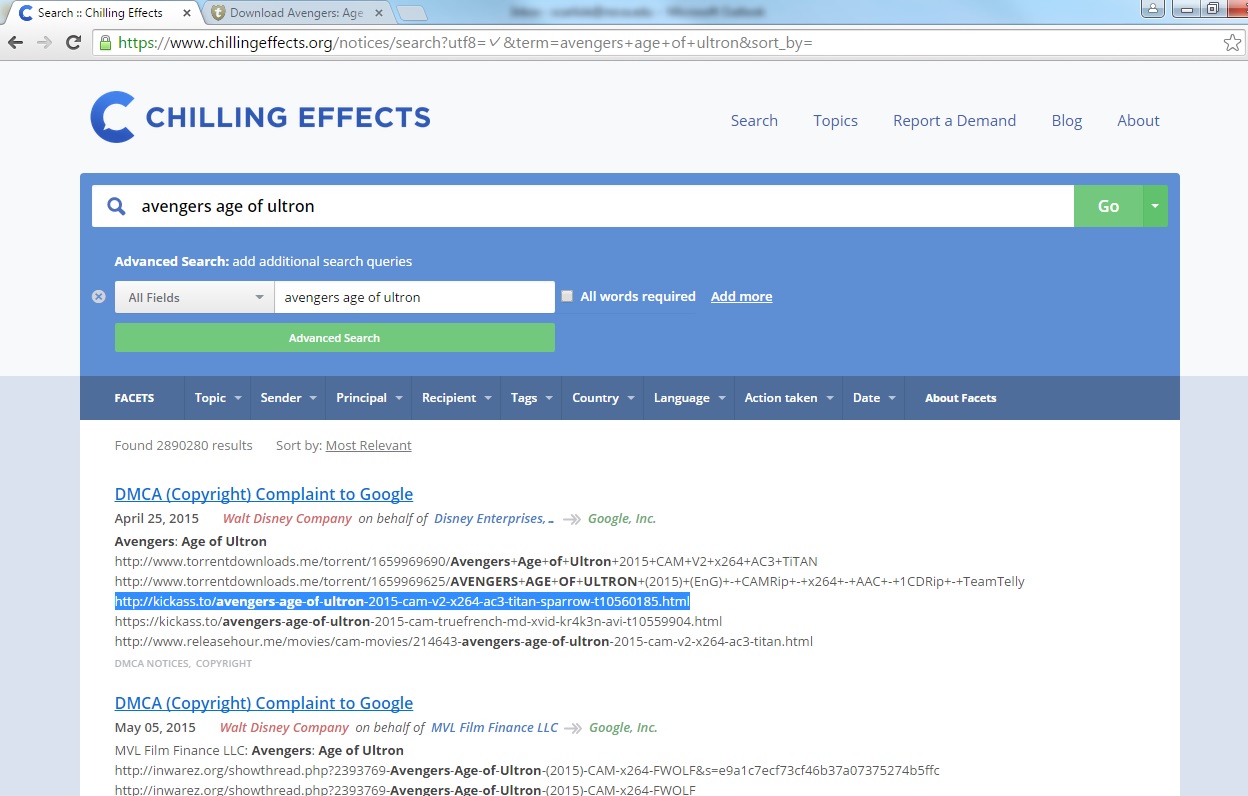

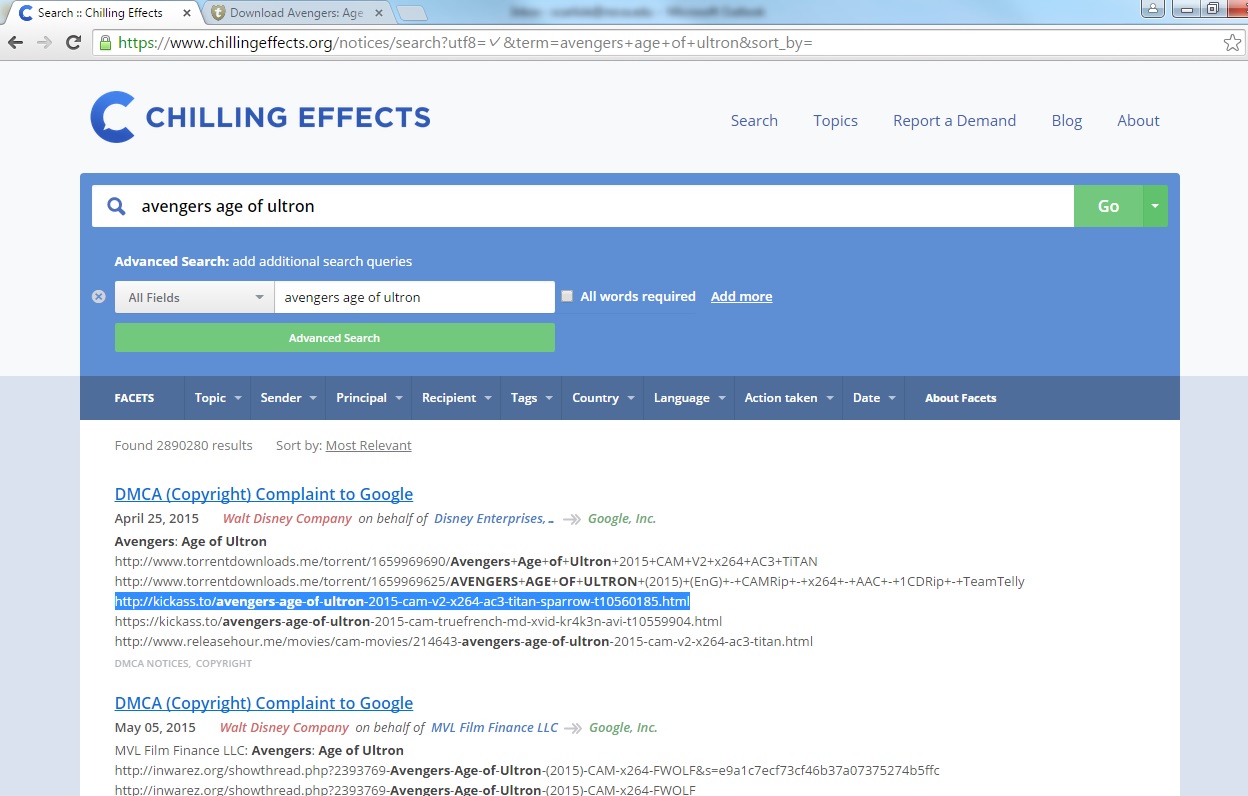

I went to the Chilling Effects website and did a search for "Avengers Age of Ultron." This is a movie which is currently still in theaters and has not been released on DVD anywhere in the world. Any copy which appears online is a pirated copy. Chilling Effects immediately spit this page back.

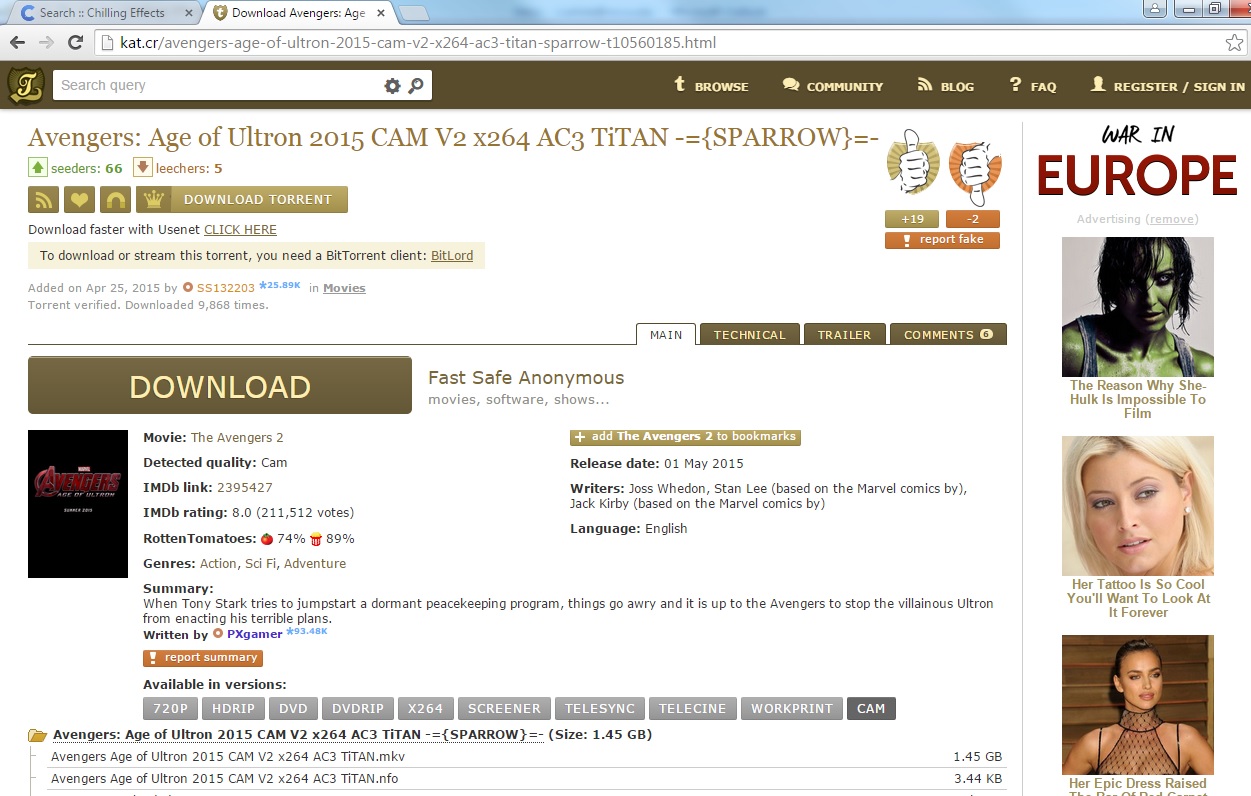

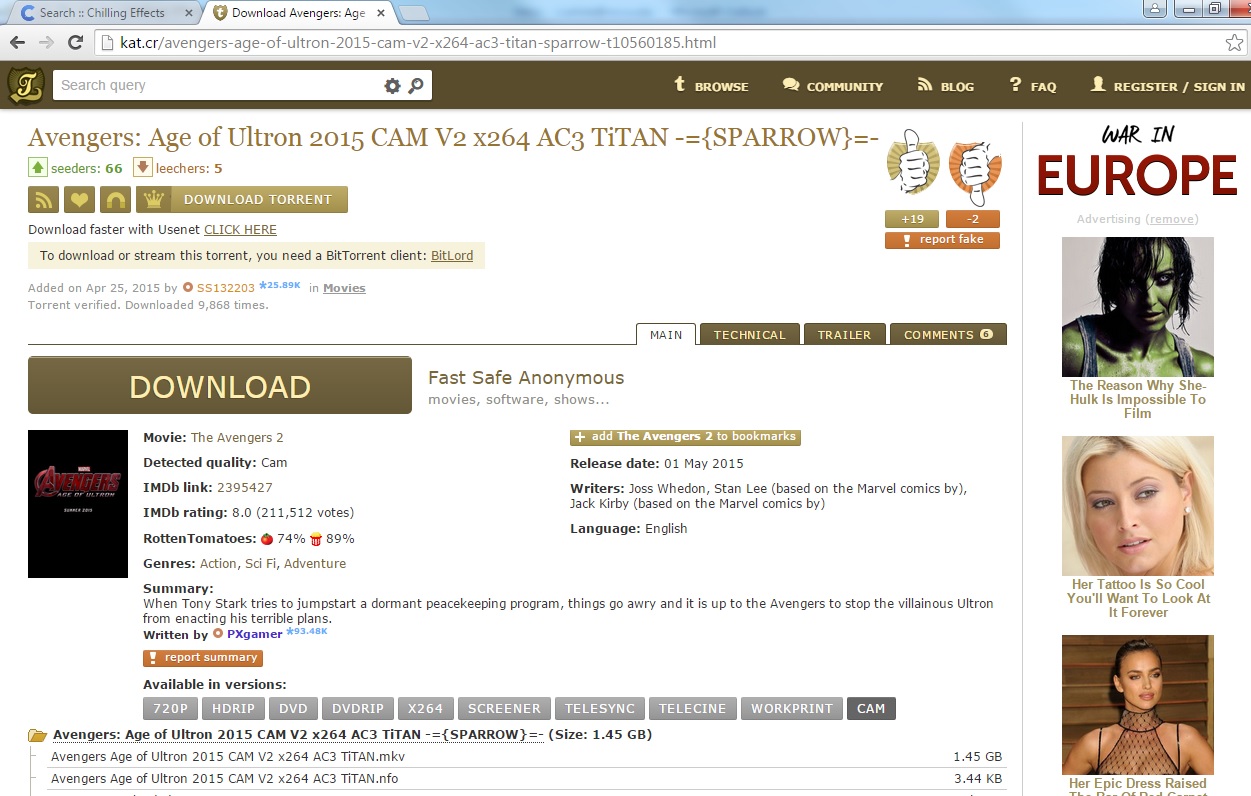

Chilling Effects just gave me a handy list of the 2.8 million places where you can find a copy of Avengers: Age of Ultron. So I picked one from the top of the list, copied and pasted it into my browser and the link took me here, the notorious pirate site Kick-Ass Torrents.

Chilling Effects just gave me a handy list of the 2.8 million places where you can find a copy of Avengers: Age of Ultron. So I picked one from the top of the list, copied and pasted it into my browser and the link took me here, the notorious pirate site Kick-Ass Torrents.

What could be easier? Simply put, Chilling Effects is actively aiding copyright piracy under the pretense of "research." They could, of course redact the URLs so as not to provide a direct link to the pirated material, but they don't. As I have written before on this blog, Chilling Effects' listing of the entire URL index provides a handy tool for pirates to keep themselves in business.[ref]Copyright Blog Update: Meet the New and Improved "Whack-A-Mole"[/ref]

What's more is Chilling Effects seems to be operating under the assumption that its activities are protected by the DMCA. I think this position is seriously in doubt.

Under Section 512(c), a website only has safe harbor immunity is if the material is posted "at the direction of a user." Chilling Effects does not qualify in this regard, because Chilling Effects is the party responsible for posting the material to its website. Under Section 512(d) there is a similar exemption for those who are "referring or linking users to an online location containing infringing material or infringing activity, by using information location tools, including a directory, index, reference, pointer, or hypertext link." Yet, to use this exemption would require that Chilling Effects

(A) does not have actual knowledge that the material or activity is infringing;

(B) in the absence of such actual knowledge, is not aware of facts or circumstances from which infringing activity is apparent; or

(C) upon obtaining such knowledge or awareness, acts expeditiously to remove, or disable access to, the material;

Chilling Effects absolutely fails these requirements.

Let's go back to my search for Avengers: Age of Ultron. Copies of this movie are not commercially available anywhere in the world. Yet Chilling Effects happily points you to a location where you can download an illegal copy. This is actual knowledge, since they clearly state that they "analyze complaints about online activity, especially requests to remove content from online." Any quick analysis, as simple as copying and pasting the URL into your browser, would show Chilling Effects that what it has posted is a link to pirated material.

What's more is Chilling Effects is reposting a legitimate takedown notice sent to Google by the Walt Disney Company, which Google has acted favorably upon. Since the very purpose of the takedown notice is to remove links to infringing activity, Chilling Effects is also "aware of facts or circumstances from which infringing activity is apparent," and has constructive knowledge as well.

Lastly, despite having actual and constructive knowledge, Chilling Effects fails to "[act] expeditiously to remove, or disable access to, the material" as they are required to do.

So what happens when you send a takedown notice to Chilling Effects? The results are truly surreal.

I have written about indie filmmaker Ellen Siedler before and her well chronicled attempts to stop piracy of her LBGT indie film And Then Came Lola. She decided to send a takedown notice to Chilling Effects, and blogged about her experience.[ref]I sent Chilling Effects a DMCA takedown notice[/ref] Firstly, Chilling Effects, even though it is required under the DMCA to have a registered agent to receive takedown notices, makes it incredibly difficult to figure out who this person is. Ellen found that the "Chilling Effects menu does not provide a direct link to info about its DMCA agent or takedown requests."[ref]Id.[/ref]

"Prior to sending my DMCA notice to the good people at Chilling Effects, I attempted to search the site for an email address to send the notice to. When I couldn't find one even after searching Google using the terms –‘chilling effects DMCA agent'— I resorted to sending my notice to the only email listed on the site's About page, team@chillingeffects.org."[ref]Id.[/ref]

"[A]fter receiving no response to my original notice, I forwarded a copy to the Berkman Center for Internet & Society. Shortly thereafter, I received an email with a link to Chilling Effects' legal policies page. (URL omitted) Of course, that was not the end of my journey. In order to get the actual email for CE's acting DMCA agent I had to click another link (URL omitted) and visit yet another website–this one a copyright infringement page hosted by Harvard University at Harvard.edu."[ref]Id.[/ref]

So how did Chilling Effects respond? They sent themselves a counter-notice.[ref]Chilling Effects sends me a DMCA counter-notice[/ref] You read that right, Chilling Effects sent a counter-notice to themselves. The notice is purportedly from the Berkman Center for Internet and Society, the same people who help run Chilling Effects. The notice says, quite unbelievably, that the material was removed by "mistake or misidentification."[ref]Id.[/ref] The defects in this notice are as follows:

What could be easier? Simply put, Chilling Effects is actively aiding copyright piracy under the pretense of "research." They could, of course redact the URLs so as not to provide a direct link to the pirated material, but they don't. As I have written before on this blog, Chilling Effects' listing of the entire URL index provides a handy tool for pirates to keep themselves in business.[ref]Copyright Blog Update: Meet the New and Improved "Whack-A-Mole"[/ref]

What's more is Chilling Effects seems to be operating under the assumption that its activities are protected by the DMCA. I think this position is seriously in doubt.

Under Section 512(c), a website only has safe harbor immunity is if the material is posted "at the direction of a user." Chilling Effects does not qualify in this regard, because Chilling Effects is the party responsible for posting the material to its website. Under Section 512(d) there is a similar exemption for those who are "referring or linking users to an online location containing infringing material or infringing activity, by using information location tools, including a directory, index, reference, pointer, or hypertext link." Yet, to use this exemption would require that Chilling Effects

(A) does not have actual knowledge that the material or activity is infringing;

(B) in the absence of such actual knowledge, is not aware of facts or circumstances from which infringing activity is apparent; or

(C) upon obtaining such knowledge or awareness, acts expeditiously to remove, or disable access to, the material;

Chilling Effects absolutely fails these requirements.

Let's go back to my search for Avengers: Age of Ultron. Copies of this movie are not commercially available anywhere in the world. Yet Chilling Effects happily points you to a location where you can download an illegal copy. This is actual knowledge, since they clearly state that they "analyze complaints about online activity, especially requests to remove content from online." Any quick analysis, as simple as copying and pasting the URL into your browser, would show Chilling Effects that what it has posted is a link to pirated material.

What's more is Chilling Effects is reposting a legitimate takedown notice sent to Google by the Walt Disney Company, which Google has acted favorably upon. Since the very purpose of the takedown notice is to remove links to infringing activity, Chilling Effects is also "aware of facts or circumstances from which infringing activity is apparent," and has constructive knowledge as well.

Lastly, despite having actual and constructive knowledge, Chilling Effects fails to "[act] expeditiously to remove, or disable access to, the material" as they are required to do.

So what happens when you send a takedown notice to Chilling Effects? The results are truly surreal.

I have written about indie filmmaker Ellen Siedler before and her well chronicled attempts to stop piracy of her LBGT indie film And Then Came Lola. She decided to send a takedown notice to Chilling Effects, and blogged about her experience.[ref]I sent Chilling Effects a DMCA takedown notice[/ref] Firstly, Chilling Effects, even though it is required under the DMCA to have a registered agent to receive takedown notices, makes it incredibly difficult to figure out who this person is. Ellen found that the "Chilling Effects menu does not provide a direct link to info about its DMCA agent or takedown requests."[ref]Id.[/ref]

"Prior to sending my DMCA notice to the good people at Chilling Effects, I attempted to search the site for an email address to send the notice to. When I couldn't find one even after searching Google using the terms –‘chilling effects DMCA agent'— I resorted to sending my notice to the only email listed on the site's About page, team@chillingeffects.org."[ref]Id.[/ref]

"[A]fter receiving no response to my original notice, I forwarded a copy to the Berkman Center for Internet & Society. Shortly thereafter, I received an email with a link to Chilling Effects' legal policies page. (URL omitted) Of course, that was not the end of my journey. In order to get the actual email for CE's acting DMCA agent I had to click another link (URL omitted) and visit yet another website–this one a copyright infringement page hosted by Harvard University at Harvard.edu."[ref]Id.[/ref]

So how did Chilling Effects respond? They sent themselves a counter-notice.[ref]Chilling Effects sends me a DMCA counter-notice[/ref] You read that right, Chilling Effects sent a counter-notice to themselves. The notice is purportedly from the Berkman Center for Internet and Society, the same people who help run Chilling Effects. The notice says, quite unbelievably, that the material was removed by "mistake or misidentification."[ref]Id.[/ref] The defects in this notice are as follows:

Chilling Effects just gave me a handy list of the 2.8 million places where you can find a copy of Avengers: Age of Ultron. So I picked one from the top of the list, copied and pasted it into my browser and the link took me here, the notorious pirate site Kick-Ass Torrents.

Chilling Effects just gave me a handy list of the 2.8 million places where you can find a copy of Avengers: Age of Ultron. So I picked one from the top of the list, copied and pasted it into my browser and the link took me here, the notorious pirate site Kick-Ass Torrents.

What could be easier? Simply put, Chilling Effects is actively aiding copyright piracy under the pretense of "research." They could, of course redact the URLs so as not to provide a direct link to the pirated material, but they don't. As I have written before on this blog, Chilling Effects' listing of the entire URL index provides a handy tool for pirates to keep themselves in business.[ref]Copyright Blog Update: Meet the New and Improved "Whack-A-Mole"[/ref]

What's more is Chilling Effects seems to be operating under the assumption that its activities are protected by the DMCA. I think this position is seriously in doubt.

Under Section 512(c), a website only has safe harbor immunity is if the material is posted "at the direction of a user." Chilling Effects does not qualify in this regard, because Chilling Effects is the party responsible for posting the material to its website. Under Section 512(d) there is a similar exemption for those who are "referring or linking users to an online location containing infringing material or infringing activity, by using information location tools, including a directory, index, reference, pointer, or hypertext link." Yet, to use this exemption would require that Chilling Effects

(A) does not have actual knowledge that the material or activity is infringing;

(B) in the absence of such actual knowledge, is not aware of facts or circumstances from which infringing activity is apparent; or

(C) upon obtaining such knowledge or awareness, acts expeditiously to remove, or disable access to, the material;

Chilling Effects absolutely fails these requirements.

Let's go back to my search for Avengers: Age of Ultron. Copies of this movie are not commercially available anywhere in the world. Yet Chilling Effects happily points you to a location where you can download an illegal copy. This is actual knowledge, since they clearly state that they "analyze complaints about online activity, especially requests to remove content from online." Any quick analysis, as simple as copying and pasting the URL into your browser, would show Chilling Effects that what it has posted is a link to pirated material.

What's more is Chilling Effects is reposting a legitimate takedown notice sent to Google by the Walt Disney Company, which Google has acted favorably upon. Since the very purpose of the takedown notice is to remove links to infringing activity, Chilling Effects is also "aware of facts or circumstances from which infringing activity is apparent," and has constructive knowledge as well.

Lastly, despite having actual and constructive knowledge, Chilling Effects fails to "[act] expeditiously to remove, or disable access to, the material" as they are required to do.

So what happens when you send a takedown notice to Chilling Effects? The results are truly surreal.

I have written about indie filmmaker Ellen Siedler before and her well chronicled attempts to stop piracy of her LBGT indie film And Then Came Lola. She decided to send a takedown notice to Chilling Effects, and blogged about her experience.[ref]I sent Chilling Effects a DMCA takedown notice[/ref] Firstly, Chilling Effects, even though it is required under the DMCA to have a registered agent to receive takedown notices, makes it incredibly difficult to figure out who this person is. Ellen found that the "Chilling Effects menu does not provide a direct link to info about its DMCA agent or takedown requests."[ref]Id.[/ref]

"Prior to sending my DMCA notice to the good people at Chilling Effects, I attempted to search the site for an email address to send the notice to. When I couldn't find one even after searching Google using the terms –‘chilling effects DMCA agent'— I resorted to sending my notice to the only email listed on the site's About page, team@chillingeffects.org."[ref]Id.[/ref]

"[A]fter receiving no response to my original notice, I forwarded a copy to the Berkman Center for Internet & Society. Shortly thereafter, I received an email with a link to Chilling Effects' legal policies page. (URL omitted) Of course, that was not the end of my journey. In order to get the actual email for CE's acting DMCA agent I had to click another link (URL omitted) and visit yet another website–this one a copyright infringement page hosted by Harvard University at Harvard.edu."[ref]Id.[/ref]

So how did Chilling Effects respond? They sent themselves a counter-notice.[ref]Chilling Effects sends me a DMCA counter-notice[/ref] You read that right, Chilling Effects sent a counter-notice to themselves. The notice is purportedly from the Berkman Center for Internet and Society, the same people who help run Chilling Effects. The notice says, quite unbelievably, that the material was removed by "mistake or misidentification."[ref]Id.[/ref] The defects in this notice are as follows:

What could be easier? Simply put, Chilling Effects is actively aiding copyright piracy under the pretense of "research." They could, of course redact the URLs so as not to provide a direct link to the pirated material, but they don't. As I have written before on this blog, Chilling Effects' listing of the entire URL index provides a handy tool for pirates to keep themselves in business.[ref]Copyright Blog Update: Meet the New and Improved "Whack-A-Mole"[/ref]

What's more is Chilling Effects seems to be operating under the assumption that its activities are protected by the DMCA. I think this position is seriously in doubt.

Under Section 512(c), a website only has safe harbor immunity is if the material is posted "at the direction of a user." Chilling Effects does not qualify in this regard, because Chilling Effects is the party responsible for posting the material to its website. Under Section 512(d) there is a similar exemption for those who are "referring or linking users to an online location containing infringing material or infringing activity, by using information location tools, including a directory, index, reference, pointer, or hypertext link." Yet, to use this exemption would require that Chilling Effects

(A) does not have actual knowledge that the material or activity is infringing;

(B) in the absence of such actual knowledge, is not aware of facts or circumstances from which infringing activity is apparent; or

(C) upon obtaining such knowledge or awareness, acts expeditiously to remove, or disable access to, the material;

Chilling Effects absolutely fails these requirements.

Let's go back to my search for Avengers: Age of Ultron. Copies of this movie are not commercially available anywhere in the world. Yet Chilling Effects happily points you to a location where you can download an illegal copy. This is actual knowledge, since they clearly state that they "analyze complaints about online activity, especially requests to remove content from online." Any quick analysis, as simple as copying and pasting the URL into your browser, would show Chilling Effects that what it has posted is a link to pirated material.

What's more is Chilling Effects is reposting a legitimate takedown notice sent to Google by the Walt Disney Company, which Google has acted favorably upon. Since the very purpose of the takedown notice is to remove links to infringing activity, Chilling Effects is also "aware of facts or circumstances from which infringing activity is apparent," and has constructive knowledge as well.

Lastly, despite having actual and constructive knowledge, Chilling Effects fails to "[act] expeditiously to remove, or disable access to, the material" as they are required to do.

So what happens when you send a takedown notice to Chilling Effects? The results are truly surreal.

I have written about indie filmmaker Ellen Siedler before and her well chronicled attempts to stop piracy of her LBGT indie film And Then Came Lola. She decided to send a takedown notice to Chilling Effects, and blogged about her experience.[ref]I sent Chilling Effects a DMCA takedown notice[/ref] Firstly, Chilling Effects, even though it is required under the DMCA to have a registered agent to receive takedown notices, makes it incredibly difficult to figure out who this person is. Ellen found that the "Chilling Effects menu does not provide a direct link to info about its DMCA agent or takedown requests."[ref]Id.[/ref]

"Prior to sending my DMCA notice to the good people at Chilling Effects, I attempted to search the site for an email address to send the notice to. When I couldn't find one even after searching Google using the terms –‘chilling effects DMCA agent'— I resorted to sending my notice to the only email listed on the site's About page, team@chillingeffects.org."[ref]Id.[/ref]

"[A]fter receiving no response to my original notice, I forwarded a copy to the Berkman Center for Internet & Society. Shortly thereafter, I received an email with a link to Chilling Effects' legal policies page. (URL omitted) Of course, that was not the end of my journey. In order to get the actual email for CE's acting DMCA agent I had to click another link (URL omitted) and visit yet another website–this one a copyright infringement page hosted by Harvard University at Harvard.edu."[ref]Id.[/ref]

So how did Chilling Effects respond? They sent themselves a counter-notice.[ref]Chilling Effects sends me a DMCA counter-notice[/ref] You read that right, Chilling Effects sent a counter-notice to themselves. The notice is purportedly from the Berkman Center for Internet and Society, the same people who help run Chilling Effects. The notice says, quite unbelievably, that the material was removed by "mistake or misidentification."[ref]Id.[/ref] The defects in this notice are as follows:

- Chilling Effects does not have safe harbor because the material is not posted by 3rd parties and it has actual and constructive knowledge of the infringing materials, and is not entitled to send a counter-notice.

- Unless the notice has been redacted by Ms. Seidler, the letter is not "signed" either directly or electronically, and is thus legally insufficient.

- The notice is not from a "subscriber" to a "service provider" as required by Section 512(g)(3). It is from a website operator to itself.

No Subjects

On June 8, 2015, Apple announced its new music streaming service, Apple Music, and took direct aim at Spotify and Pandora.[ref]Apple Takes on Spotify with New Music Service[/ref] This move capped a busy month of court rulings, document leaks, and more than a little finger pointing and name calling in the pitched battle between content creators and the streaming services. To recap:

- On May 19, 2015, persons unknown (but all available evidence points to Spotify) leaked the contract between Sony Music and Spotify to the website The Verge.[ref]This was Sony Music's contract with Spotify[/ref] (NB: The actual contract has been removed, but the link will take you to an in depth discussion of its terms.)

- Just four days later, on May 23, 2105, in an interview with the New York Post, Spotify CEO Daniel Ek said that "greedy middlemen" were responsible for the microscopic payments musicians and composers receive from Spotify.[ref]Spotify CEO says middlemen gobble cash[/ref]

- On May 27, 2015, Judge Gutierrez granted Flo and Eddie's Motion for Class Action Certification in their case against Sirius XM Radio[ref]Another Artist Rights Victory: Turtles Win Class Certification in Class Action Against SiriusXM #irespectmusic[/ref] (this link has a further link to the opinion), a lawsuit previously discussed in depth on this blog.[ref]Flo and Eddie v. Sirius XM Radio: Have Two Hippies from the 60's Just Changed the Course of Broadcast Music?[/ref] This order has been stayed pending an appeal.

- The same day, Judge Louis Stanton of the District Court for the Southern District of New York ruled that Pandora has to pay 2.5% of gross revenue to BMI, the performing rights organization that represents music publishers and composers.[ref]Broadcast Music, Inc. v. Pandora Media, Inc. 2015 WL 3526105 United States District Court, for the Southern District of New York, 2015 at page 60.[/ref] Pandora was seeking a rate between 1.7% and 1.85% of gross revenue.[ref]Id. at 6[/ref]

No Subjects