Two recent events cast a spotlight on the not-so-funny business of joke stealing. In the first few weeks of July, Twitter received DMCA takedown notices from freelance writer Olga Lexall, who objected the re-tweeting of her jokes without attribution.[ref]Why are some jokes being hidden on Twitter?[/ref] Twitter, in turn, removed the re-tweeted jokes and replaced them with a notification that the material had been removed due to a "report from the copyright holder."[ref]Id.[/ref]

Actual lawsuits between comedians are so rare as to be unheard of. Yet, on July 22, 2015, an actual copyright infringement lawsuit over jokes was filed by Robert "Alex" Kaseberg, against Conan O'Brien and his production company.[ref]Kaseberg v. Conaco LLC, et al Case No. 15CV1637 JLS DHB. U.S. District Court for the Southern District of California 2015 WL 4497791[/ref] Kaseberg claims that on four different occasions after posting jokes on his personal blog and Twitter account, the nearly identical jokes were delivered by Conan O'Brien on his television show, sometimes in less than a day than they first appeared.[ref]Id.[/ref] Kaseberg claims to have been a writer for the "Tonight Show" for over 20 years.[ref]Conan O'Brien Targeted in Lawsuit Claiming He Lifted Jokes from Twitter[/ref] In response to the suit, the Conan O'Brien parties issued the standard denial of "there is no merit to this lawsuit."[ref]Id.[/ref]

Joke stealing is considered a serious offence within the stand-up comedy community. Yet, comedians as notable as Robin Williams, Dennis Leary, Dane Cook, Carlos Mencia,[ref]Jokes and Copyright[/ref] Jay Leno,[ref]Entry 7: Who owns a joke? And can a comedian sue if someone steals his material?[/ref] and the TV show South Park[ref]So You Want to Accuse Someone of Stealing Your Joke[/ref] have all been accused of joke stealing. Milton Berle was accused of joke stealing so many times that many comedians referred to him as "The Thief of Bad Gag."[ref]Entry 7: Who owns a joke? And can a comedian sue if someone steals his material?[/ref]

There is an unspoken understanding amongst comedians about who owns a joke.

"If two comics come up with a similar joke, for example, it's understood that whoever tells it first on television can claim ownership. Similarly, if two comedians are working on material together, batting ideas back and forth, it's generally agreed upon that if one comedian comes up with a setup and the other the punch line, the former owns the joke."[ref]Id.[/ref]

And of course, there are some instances of self-help in combatting joke stealers. W.C. Fields is said to have paid $50 to break the legs of a comedian who stole his jokes.[ref]Why It's So Hard to Get the Law to Protect a Good Joke (Guest Column)[/ref]

"According to Richard Zoglin's book, Comedy at the Edge, David Brenner once asked [Robin] Williams' agent to ‘Tell Robin if he ever takes one more line from me, I'll rip his leg off and shove it up his [bleep]!' Williams has playfully referred to the practice as ‘joke sampling.'"[ref]Stop Me If You've Heard This Before: A Look at Comedy Plagiarism[/ref]

In 2007, there was a rather ugly confrontation between Joe Rogan and Carlos Mencia while the latter was onstage performing a show at the Comedy Store in Hollywood California.[ref]Id.[/ref]

One comedian [was of the opinion], "… the only copyright protection you have is a quick uppercut."[ref]Entry 7: Who owns a joke? And can a comedian sue if someone steals his material?[/ref]

Will copyright protect a joke? The Copyright Office seems to think so, with limitations.

"Compendium II of Copyright Office Practices § 420.02 states: ‘Jokes and other comedy routines may be registered if they contain at least a certain minimum amount of original expression in tangible form. Short quips and slang expressions consisting of no more than short expressions are not registrable.' In other words, jokes are to be considered under the ordinary originality standard applied to all other material."[ref]Jokes and Copyright[/ref]

Since, as noted above, the Copyright Office will refuse to register short phrases, "one-liner" jokes such as Henny Youngman's famous quip "Take my wife…please" might be in danger of being refused copyright registration.

One must also consider the fixation problem. If the joke has only been delivered in a live stand-up comedy show, then the joke fails the requirement on fixation. If that joke gets stolen, there might be recourse through common law misappropriation (or a quick uppercut), but not copyright infringement.

Then, there is the originality problem. Your joke might be original, or it might be that you have just forgotten where you heard it first.

"In a lengthy essay on joke stealing, Patton Oswalt admitted to having done this early in his career: ‘I stole a joke. Not consciously. I heard something I found hilarious, mis-remembered it as an inspiration of my own, and then said it onstage.'"[ref]Entry 7: Who owns a joke? And can a comedian sue if someone steals his material?[/ref]

And finally, there is the doctrine of independent creation. Two comedians could come up with the same joke independently, as Bill Maher found out.

"Nothing shuts down an accusation of joke theft faster or in a more embarrassing way than proof that the accuser actually made the joke after the accused. That's what happened to Bill Maher, who accused The Onion of stealing a joke he made in a standup special. The problem? The Onion published the joke in question six months before his standup special aired. He had just seen it brought back from the archives on the front page and assumed it was new."[ref]So You Want to Accuse Someone of Stealing Your Joke[/ref]

Or, there's this very blog post. After I had written about half of it, I did a little more research, only to find an article on the same topic using nearly the same headline that I had already picked out.[ref]Stop Me If You've Heard This Before: A Look at Comedy Plagiarism[/ref]

So, let's go back to the Conan O'Brien lawsuit.

Kaseberg claims that his jokes went out as posting on his personal blog and as tweets on his Twitter account.[ref]Kaseberg v. Conaco LLC, et al Case No. 15CV1637 JLS DHB. 2015 WL 4497791[/ref] That seems to have solved the fixation problem, but there is a complicating factor: Twitter automatically deletes tweets after about one and a half weeks, making them unsearchable in the Twitter database.[ref]10 Ways to Archive Your Tweets[/ref] So, while the several months old tweets by Kaseberg will remain in his Twitter stream, there will be no way to independently verify them from the defense side of the table.

A further complicating factor is that Kaseberg has only filed for registration, but not received the actual registrations back.[ref]Kaseberg v. Conaco LLC, et al Case No. 15CV1637 JLS DHB. 2015 WL 4497791[/ref] As stated above, assuming that the Copyright Office will actually grant registration to the jokes is not a foregone conclusion.

But, ultimately the case will turn on the question of access, and whether the jokes are so substantially similar that Kaseberg's public dissemination of the jokes by Twitter and his personal blog is sufficient to assume access by Conan O'Brien and his writing staff.

And, in the meantime, the amount of attorneys' fees expended in this case will be no laughing matter.

The days of whispering on the phone and the "no-tell motel" seem to be over. The internet has taken over the job of connecting people who wish to cheat on their spouses. But, as with all things secret, sometimes they get found out.

On June 19, 2015, online reporter Brian Krebs broke the story that the online service for cheating spouses, Ashley Madison, had been hacked.[ref]Online Cheating Site AshleyMadison Hacked[/ref] The hackers demanded the parent company, Avid Dating Life[ref]Avid Life Media is the overall holding company, but Avid Dating Life is the company responsible for running Ashley Madison, and thus ADL will be used for purposes of clarity.[/ref]:

"take Ashley Madison and Established Men offline permanently in all forms, or we will release all customer records, including profiles with all the customers' secret sexual fantasies and matching credit card transactions, real names and addresses, and employee documents and emails."[ref]Id.[/ref]

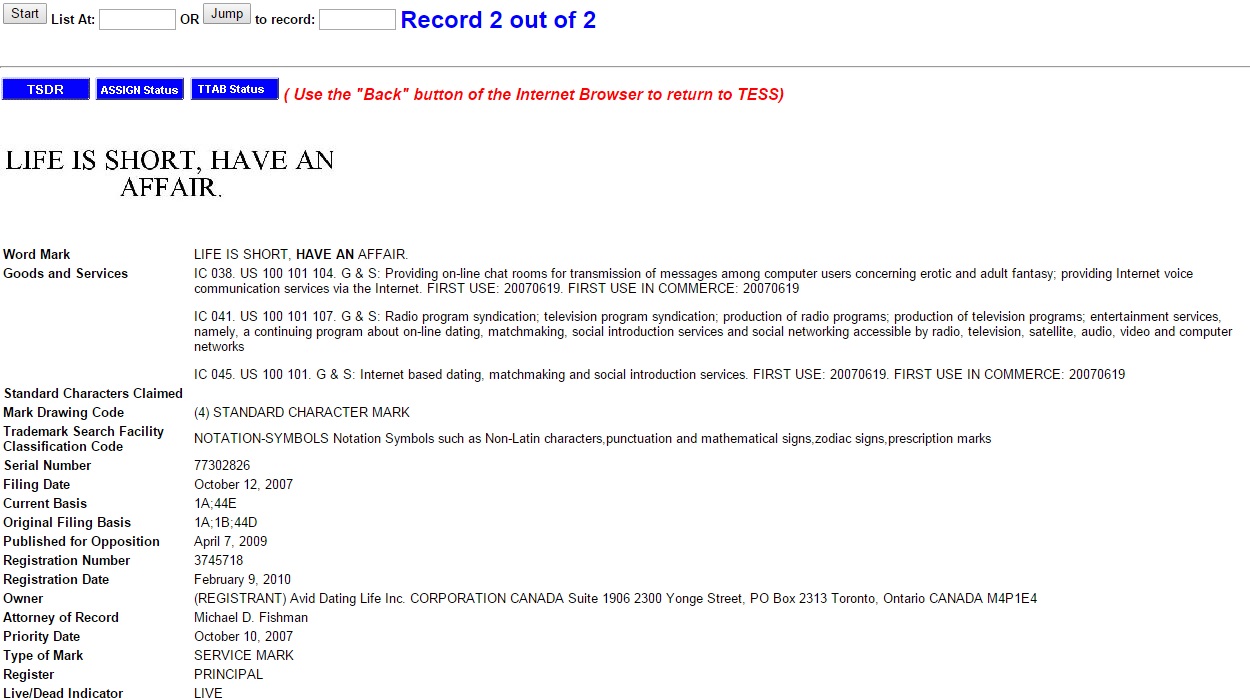

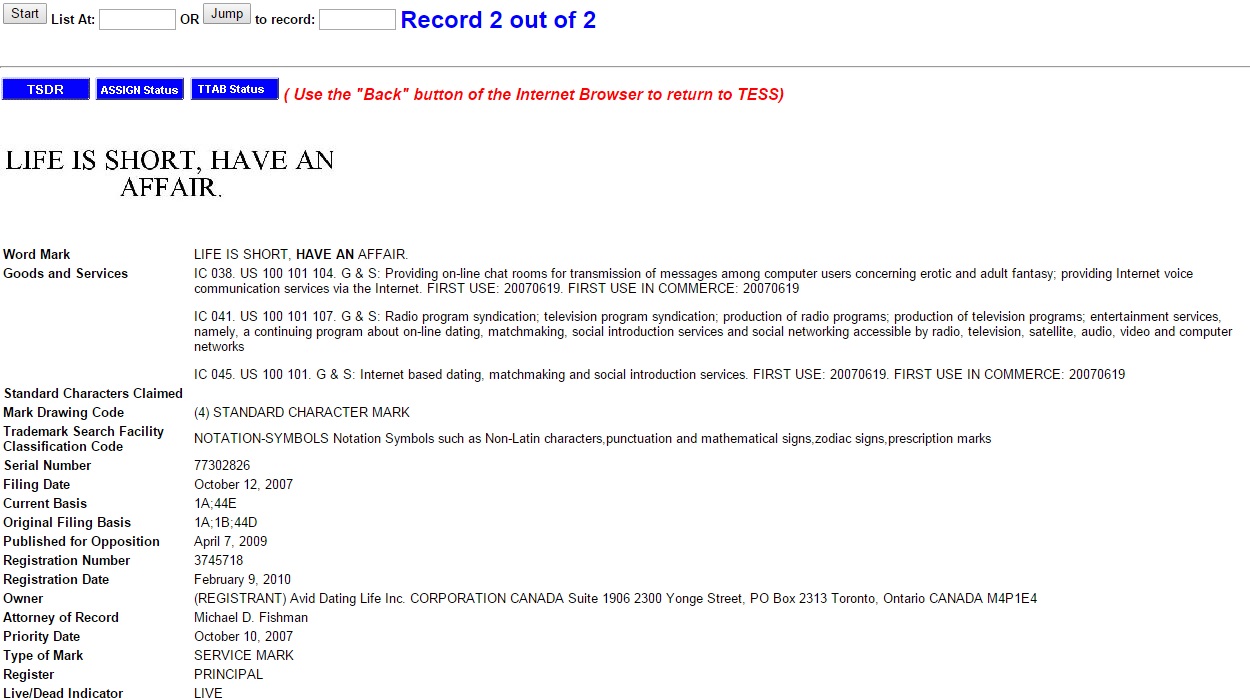

Not exactly the thing a cheating spouse wants to hear, especially one that is sneaking around an online "cheating service." Yet, this is not the first time this has happened. A similar company, Adult Friend Finder was hacked only two months before,[ref]Id. citing Adult dating site hack exposes sexual secrets of millions[/ref] with Krebs reporting that the Wall Street Journal published an article which predicted trouble for Ashley Madison as a result of AFF hack.[ref]Online Cheating Site AshleyMadison Hacked citing Risky Business for AshleyMadison.com[/ref] Adult Friend Finder is more of a "hook-up" site for swingers, as opposed to Ashley Madison, which openly caters to cheating spouses and has the audacity to have a Federal Trademark on the slogan "Life Is Short. Have An Affair."

Ashley Madison also claims to have 37 million users, though one of the complaints leveled at AM is that many of the female profiles are fake.[ref]The Ashley Madison hack, explained[/ref] Still, that would lead to a lot of nervous customers who don't want to be found out.

Yet, the hackers' main beef with ADL is not the morally dubious nature of the site, but rather is due to a "service" that will remove all of a client's information from their database - for a price.[ref]Online Cheating Site AshleyMadison Hacked[/ref]

"According to the hackers, although the "full delete" feature that Ashley Madison advertises promises "removal of site usage history and personally identifiable information from the site," users' purchase details — including real name and address — aren't actually scrubbed."[ref]Id.[/ref]

"Full Delete netted ALM $1.7mm in revenue in 2014. It's also a complete lie," the hacking group wrote. "Users almost always pay with credit card; their purchase details are not removed as promised, and include real name and address, which is of course the most important information the users want removed."[ref]Id.[/ref]

So far, ADL has combatted those leaks which do appear by sending DMCA notices to the offending sites.

"'Using the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), our team has now successfully removed all posts related to this incident as well as all Personally Identifiable Information (PII) about our users published online,' said Ashley Madison parent company Avid Life Media in a statement. ‘We have always had the confidentiality of our customers' information foremost in our minds and are pleased that the provisions included in the DMCA have been effective in addressing this matter.'"[ref]A 1990s anti-piracy law is why you haven't seen the hacked list of Ashley Madison customers[/ref]

Predictably, the Electronic Frontier Foundation howled with outrage,[ref]Id.[/ref] but in this case I happen to agree with them. Along with the opinions offered by other pro-artist voices such as Ellen Siedler's Vox Indie [ref]Using DMCA to fight Ashley Madison hackers is poor use of copyright law[/ref] and Jonathan Bailey over at Plagiarism Today,[ref]3 Count: Cheat Code[/ref] this is a very dubious use, if not an outright abuse of the DMCA takedown system.

The problem here is that there does not seem to be any copyright that ALM or Ashley Madison might hold that they can lawfully assert via a DMCA notice.

This blog has detailed before the use of the DMCA to assist in the takedown of the hacked nude photographs of various celebrities.[ref]Unintended Consequences: How the DMCA Made the Distribution of Stolen Celebrity Photos All Too Easy[/ref] However, this is predicated on the fact that somebody (presumably the picture taker if the picture is a "selfie"), has a valid copyright in the photograph. Certainly, one can have a copyright in a compilation or a database. This is predicated on the author's arrangement and selection of the various facts included.[ref]Feist Publication Inc. v. Rural Telephone Service, Inc. 499 U.S. 340 Supreme Court of the United States (1991)[/ref]

However, this is not the case here. The facts aggregated by ADL are purely the result of who signs up for the service, and who has removed themselves from the database by deleting their account. In other words, the facts have self-selected themselves. Says the Supreme Court of the United States:

"one who discovers a fact is not its "maker" or "originator." [citation omitted] "The discoverer merely finds and records." Nimmer [on Copyright] § 2.03[E]. Census takers, for example, do not "create" the population figures that emerge from their efforts; in a sense, they copy these figures from the world around them" … [c]ensus data therefore do not trigger copyright because these data are not "original" in the constitutional sense."[ref]Id. at 347[/ref]

The case for ADL gets worse when one considers that only a small portion of the database has been made public.[ref]Online Cheating Site AshleyMadison Hacked[/ref] Even if ADL could claim a copyright in the entire database, this does not necessarily attach to the individual sets of facts within that database.

So what about the photographs and profile descriptions? They would qualify if ALM became the copyright owner or an exclusive license holder by its Terms of Service. It does not appear that this has happened. According to Ashley Madison's Terms of Service:

"USER CONTENT

Ashley Madison also claims to have 37 million users, though one of the complaints leveled at AM is that many of the female profiles are fake.[ref]The Ashley Madison hack, explained[/ref] Still, that would lead to a lot of nervous customers who don't want to be found out.

Yet, the hackers' main beef with ADL is not the morally dubious nature of the site, but rather is due to a "service" that will remove all of a client's information from their database - for a price.[ref]Online Cheating Site AshleyMadison Hacked[/ref]

"According to the hackers, although the "full delete" feature that Ashley Madison advertises promises "removal of site usage history and personally identifiable information from the site," users' purchase details — including real name and address — aren't actually scrubbed."[ref]Id.[/ref]

"Full Delete netted ALM $1.7mm in revenue in 2014. It's also a complete lie," the hacking group wrote. "Users almost always pay with credit card; their purchase details are not removed as promised, and include real name and address, which is of course the most important information the users want removed."[ref]Id.[/ref]

So far, ADL has combatted those leaks which do appear by sending DMCA notices to the offending sites.

"'Using the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), our team has now successfully removed all posts related to this incident as well as all Personally Identifiable Information (PII) about our users published online,' said Ashley Madison parent company Avid Life Media in a statement. ‘We have always had the confidentiality of our customers' information foremost in our minds and are pleased that the provisions included in the DMCA have been effective in addressing this matter.'"[ref]A 1990s anti-piracy law is why you haven't seen the hacked list of Ashley Madison customers[/ref]

Predictably, the Electronic Frontier Foundation howled with outrage,[ref]Id.[/ref] but in this case I happen to agree with them. Along with the opinions offered by other pro-artist voices such as Ellen Siedler's Vox Indie [ref]Using DMCA to fight Ashley Madison hackers is poor use of copyright law[/ref] and Jonathan Bailey over at Plagiarism Today,[ref]3 Count: Cheat Code[/ref] this is a very dubious use, if not an outright abuse of the DMCA takedown system.

The problem here is that there does not seem to be any copyright that ALM or Ashley Madison might hold that they can lawfully assert via a DMCA notice.

This blog has detailed before the use of the DMCA to assist in the takedown of the hacked nude photographs of various celebrities.[ref]Unintended Consequences: How the DMCA Made the Distribution of Stolen Celebrity Photos All Too Easy[/ref] However, this is predicated on the fact that somebody (presumably the picture taker if the picture is a "selfie"), has a valid copyright in the photograph. Certainly, one can have a copyright in a compilation or a database. This is predicated on the author's arrangement and selection of the various facts included.[ref]Feist Publication Inc. v. Rural Telephone Service, Inc. 499 U.S. 340 Supreme Court of the United States (1991)[/ref]

However, this is not the case here. The facts aggregated by ADL are purely the result of who signs up for the service, and who has removed themselves from the database by deleting their account. In other words, the facts have self-selected themselves. Says the Supreme Court of the United States:

"one who discovers a fact is not its "maker" or "originator." [citation omitted] "The discoverer merely finds and records." Nimmer [on Copyright] § 2.03[E]. Census takers, for example, do not "create" the population figures that emerge from their efforts; in a sense, they copy these figures from the world around them" … [c]ensus data therefore do not trigger copyright because these data are not "original" in the constitutional sense."[ref]Id. at 347[/ref]

The case for ADL gets worse when one considers that only a small portion of the database has been made public.[ref]Online Cheating Site AshleyMadison Hacked[/ref] Even if ADL could claim a copyright in the entire database, this does not necessarily attach to the individual sets of facts within that database.

So what about the photographs and profile descriptions? They would qualify if ALM became the copyright owner or an exclusive license holder by its Terms of Service. It does not appear that this has happened. According to Ashley Madison's Terms of Service:

"USER CONTENT

Ashley Madison also claims to have 37 million users, though one of the complaints leveled at AM is that many of the female profiles are fake.[ref]The Ashley Madison hack, explained[/ref] Still, that would lead to a lot of nervous customers who don't want to be found out.

Yet, the hackers' main beef with ADL is not the morally dubious nature of the site, but rather is due to a "service" that will remove all of a client's information from their database - for a price.[ref]Online Cheating Site AshleyMadison Hacked[/ref]

"According to the hackers, although the "full delete" feature that Ashley Madison advertises promises "removal of site usage history and personally identifiable information from the site," users' purchase details — including real name and address — aren't actually scrubbed."[ref]Id.[/ref]

"Full Delete netted ALM $1.7mm in revenue in 2014. It's also a complete lie," the hacking group wrote. "Users almost always pay with credit card; their purchase details are not removed as promised, and include real name and address, which is of course the most important information the users want removed."[ref]Id.[/ref]

So far, ADL has combatted those leaks which do appear by sending DMCA notices to the offending sites.

"'Using the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), our team has now successfully removed all posts related to this incident as well as all Personally Identifiable Information (PII) about our users published online,' said Ashley Madison parent company Avid Life Media in a statement. ‘We have always had the confidentiality of our customers' information foremost in our minds and are pleased that the provisions included in the DMCA have been effective in addressing this matter.'"[ref]A 1990s anti-piracy law is why you haven't seen the hacked list of Ashley Madison customers[/ref]

Predictably, the Electronic Frontier Foundation howled with outrage,[ref]Id.[/ref] but in this case I happen to agree with them. Along with the opinions offered by other pro-artist voices such as Ellen Siedler's Vox Indie [ref]Using DMCA to fight Ashley Madison hackers is poor use of copyright law[/ref] and Jonathan Bailey over at Plagiarism Today,[ref]3 Count: Cheat Code[/ref] this is a very dubious use, if not an outright abuse of the DMCA takedown system.

The problem here is that there does not seem to be any copyright that ALM or Ashley Madison might hold that they can lawfully assert via a DMCA notice.

This blog has detailed before the use of the DMCA to assist in the takedown of the hacked nude photographs of various celebrities.[ref]Unintended Consequences: How the DMCA Made the Distribution of Stolen Celebrity Photos All Too Easy[/ref] However, this is predicated on the fact that somebody (presumably the picture taker if the picture is a "selfie"), has a valid copyright in the photograph. Certainly, one can have a copyright in a compilation or a database. This is predicated on the author's arrangement and selection of the various facts included.[ref]Feist Publication Inc. v. Rural Telephone Service, Inc. 499 U.S. 340 Supreme Court of the United States (1991)[/ref]

However, this is not the case here. The facts aggregated by ADL are purely the result of who signs up for the service, and who has removed themselves from the database by deleting their account. In other words, the facts have self-selected themselves. Says the Supreme Court of the United States:

"one who discovers a fact is not its "maker" or "originator." [citation omitted] "The discoverer merely finds and records." Nimmer [on Copyright] § 2.03[E]. Census takers, for example, do not "create" the population figures that emerge from their efforts; in a sense, they copy these figures from the world around them" … [c]ensus data therefore do not trigger copyright because these data are not "original" in the constitutional sense."[ref]Id. at 347[/ref]

The case for ADL gets worse when one considers that only a small portion of the database has been made public.[ref]Online Cheating Site AshleyMadison Hacked[/ref] Even if ADL could claim a copyright in the entire database, this does not necessarily attach to the individual sets of facts within that database.

So what about the photographs and profile descriptions? They would qualify if ALM became the copyright owner or an exclusive license holder by its Terms of Service. It does not appear that this has happened. According to Ashley Madison's Terms of Service:

"USER CONTENT

Ashley Madison also claims to have 37 million users, though one of the complaints leveled at AM is that many of the female profiles are fake.[ref]The Ashley Madison hack, explained[/ref] Still, that would lead to a lot of nervous customers who don't want to be found out.

Yet, the hackers' main beef with ADL is not the morally dubious nature of the site, but rather is due to a "service" that will remove all of a client's information from their database - for a price.[ref]Online Cheating Site AshleyMadison Hacked[/ref]

"According to the hackers, although the "full delete" feature that Ashley Madison advertises promises "removal of site usage history and personally identifiable information from the site," users' purchase details — including real name and address — aren't actually scrubbed."[ref]Id.[/ref]

"Full Delete netted ALM $1.7mm in revenue in 2014. It's also a complete lie," the hacking group wrote. "Users almost always pay with credit card; their purchase details are not removed as promised, and include real name and address, which is of course the most important information the users want removed."[ref]Id.[/ref]

So far, ADL has combatted those leaks which do appear by sending DMCA notices to the offending sites.

"'Using the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), our team has now successfully removed all posts related to this incident as well as all Personally Identifiable Information (PII) about our users published online,' said Ashley Madison parent company Avid Life Media in a statement. ‘We have always had the confidentiality of our customers' information foremost in our minds and are pleased that the provisions included in the DMCA have been effective in addressing this matter.'"[ref]A 1990s anti-piracy law is why you haven't seen the hacked list of Ashley Madison customers[/ref]

Predictably, the Electronic Frontier Foundation howled with outrage,[ref]Id.[/ref] but in this case I happen to agree with them. Along with the opinions offered by other pro-artist voices such as Ellen Siedler's Vox Indie [ref]Using DMCA to fight Ashley Madison hackers is poor use of copyright law[/ref] and Jonathan Bailey over at Plagiarism Today,[ref]3 Count: Cheat Code[/ref] this is a very dubious use, if not an outright abuse of the DMCA takedown system.

The problem here is that there does not seem to be any copyright that ALM or Ashley Madison might hold that they can lawfully assert via a DMCA notice.

This blog has detailed before the use of the DMCA to assist in the takedown of the hacked nude photographs of various celebrities.[ref]Unintended Consequences: How the DMCA Made the Distribution of Stolen Celebrity Photos All Too Easy[/ref] However, this is predicated on the fact that somebody (presumably the picture taker if the picture is a "selfie"), has a valid copyright in the photograph. Certainly, one can have a copyright in a compilation or a database. This is predicated on the author's arrangement and selection of the various facts included.[ref]Feist Publication Inc. v. Rural Telephone Service, Inc. 499 U.S. 340 Supreme Court of the United States (1991)[/ref]

However, this is not the case here. The facts aggregated by ADL are purely the result of who signs up for the service, and who has removed themselves from the database by deleting their account. In other words, the facts have self-selected themselves. Says the Supreme Court of the United States:

"one who discovers a fact is not its "maker" or "originator." [citation omitted] "The discoverer merely finds and records." Nimmer [on Copyright] § 2.03[E]. Census takers, for example, do not "create" the population figures that emerge from their efforts; in a sense, they copy these figures from the world around them" … [c]ensus data therefore do not trigger copyright because these data are not "original" in the constitutional sense."[ref]Id. at 347[/ref]

The case for ADL gets worse when one considers that only a small portion of the database has been made public.[ref]Online Cheating Site AshleyMadison Hacked[/ref] Even if ADL could claim a copyright in the entire database, this does not necessarily attach to the individual sets of facts within that database.

So what about the photographs and profile descriptions? They would qualify if ALM became the copyright owner or an exclusive license holder by its Terms of Service. It does not appear that this has happened. According to Ashley Madison's Terms of Service:

"USER CONTENT

- By submitting any content (including, without limitation, your photograph and profile and other information) to our Site, you represent and warrant to us that the content, including your photograph, is posted by you and that you are the exclusive author of the content, including your photograph, and use of your content by us will not infringe or violate the intellectual property or other rights of any third party… By submitting any content (including, without limitation, your photograph and profile) to our Site, you automatically grant, and you represent and warrant that you have the right to grant, to us, and our licensees, parent, subsidiaries, affiliates and successors, an unlimited, perpetual, worldwide, non-exclusive, royalty-free irrevocable, transferable right and license to use, reproduce, display, broadcast, publish, quote, re-post, reproduce, bundle, distribute, create derivative works of, adapt, translate, transmit, arrange, sub-license, export, outsource, loan, lease, rent, share, assign and modify such content or incorporate into other works such content, and to grant and to authorize sub-licenses and other transfers of the foregoing."

- You are solely responsible for any content that you submit, post or transmit via our Service.[ref]Ashley Madison Terms and Conditions (emphasis added)[/ref]

- "COPYRIGHT POLICY

- "Privacy & Use of Information

No Subjects

An all singing, all dancing James Bond? As far-fetched as it may sound, on June 30, 2015, Merry Saltzman, daughter of the late Bond film producer Harry Saltzman, announced that she was going to be staging a James Bond musical, either on Broadway or Las Vegas.[ref]James Bond Broadway Musical Promises "Our Own Bond Girl" - Exclusive Details Revealed[/ref] My reaction was probably shared by the vast majority of Bond fans around the world…please do not do this!

But make no mistake, she did not get the rights by way of her late father. Harry Saltzman sold his share of the Bond empire to United Artists in 1975.[ref]Plans for James Bond musical shot down by rights' holders[/ref] Immediately after the news of the musical Bond broke, Danjaq LLC (who controls Eon Productions and the Bond film franchise) scoffed at the whole notion. As posted on the official James bond website:

"Danjaq LLC and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc. confirm they have not licensed any rights to Merry Saltzman or her production company to create a James Bond musical. Danjaq and MGM jointly control all live stage rights in the Bond franchise, and therefore no James Bond stage show may be produced without their permission."[ref]Bond Statement[/ref]

So how does she propose to proceed? Simple. She contends that her musical is a "parody" of James Bond and is thus permissible. As reported by Playbill, Merry Saltzman contends:

"Eon, Danjaq, and MGM et al's statements are accurate as far as they go. Placeholder Productions' and my statements are also accurate. Placeholder did not claim to have purchased rights to a stage production from Eon et al (nor did we intend to imply we had).

"Placeholder did (and did claim to) purchase rights to a James Bond musical parody written by Dave Clarke with music and lyrics by Jay Henry Weisz.

"The key word here is 'parody.' Parody, the courts have repeatedly upheld, is fully protected under the fair use principle of the US Copyright Act of 1976 and, as such, does not require permission from the owners of the intellectual property being parodied. We are producing a parody, no permissive rights are required from Eon, Danjaq, MGM et al to produce our show; it will not infringe on their intellectual property. James Bond: The Musical will go on as planned."[ref]James Bond Musical Producer Says Broadway "Parody" Will Go on as Planned[/ref]

Unfortunately for Ms. Saltzman, the law is far from clear on this point. According to the Supreme Court of the United States:

"Like a book review quoting the copyrighted material criticized, parody may or may not be fair use, and petitioners' suggestion that any parodic use is presumptively fair has no more justification in law or fact than the equally hopeful claim that any use for news reporting should be presumed fair."[ref]Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc. 510 US 569 Supreme Court of the United States (1994) at 581[/ref]

Certainly, the claim of being a James Bond "parody" was not a winning argument for the American Honda corporation in litigation brought by the Bond producers over Honda's "James Bond lite" commercial for their Honda Del Sol automobile.[ref]Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc v. American Honda Motor Co. 900 F.Supp. 1287 United States District Court, C.D. California. 1995[/ref] The Court dismissed this defense and entered a preliminary injunction against them. If interested, you can view the commercial here:[ref]honda del sol commercial[/ref]

https://youtu.be/gqa-b3assCA

Without a doubt, no one has taken more comedic shots at James Bond than the Austin Powers movies. The website Universal Exports has a rather detailed list of the 61 different Bond references in the Austin Powers series.[ref]The Austin Powers and James Bond Connection[/ref] (N.B. as all Bond fans know, Universal Exports is the company Bond claims to work for when on assignment)

Yet even then, the Bond producers felt a line had been crossed with the third Powers movie "Goldmember."

"MGM and Danjaq, …obtained a cease-and-desist order from the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) arbitration panel on the grounds that New Line was attempting to trade on the James Bond franchise without authorization. The matter went to arbitration and the film was known briefly as ‘The third installment of Austin Powers' until the matter was settled on 11 April 2002. MGM agreed that New Line could use the original Goldmember title on condition that it had approval of any future titles that parodied existing Bond titles."[ref]20 Things You Might Not Know About The Austin Powers Films[/ref]

And even though not a parody, the Bond producers filed a lawsuit against Universal over the film Section 6, that they felt poached on their territory.[ref]MGM, James Bond Producers Sue Universal Over 'Section 6' Project[/ref] What was unusual was that the suit was filed just on the basis of the screenplay, and not on the finished film.[ref]Id.[/ref] The case was later settled.

Based upon history, the Bond producers will be more than ready to file a lawsuit against Merry Saltzman. So what is the legal standard for whether a parody infringes upon the original? Obviously the parody has to make some use of the protected material, or else the audience will have no idea what is being sent up. Not surprisingly, the answer is "it depends." The Supreme Court stated:

"The fact that parody can claim legitimacy for some appropriation does not, of course, tell either parodist or judge much about where to draw the line… [t]he Act has no hint of an evidentiary preference for parodists over their victims, and no workable presumption for parody could take account of the fact that parody often shades into satire when society is lampooned through its creative artifacts, or that a work may contain both parodic and nonparodic elements. Accordingly parody, like any other use, has to work its way through the relevant factors [of fair use], and be judged case by case, in light of the ends of the copyright law."[ref]Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc. at 581[/ref]

"This is not, of course, to say that anyone who calls himself a parodist can skim the cream and get away scot free. In parody, as in news reporting, [citation omitted] context is everything."[ref]Id. at 589[/ref]

The Judge in the American Honda case had this to say:

"[T]he Court must look to the quantitative and qualitative extent of the copying involved. A parodist may appropriate only that amount of the original necessary to achieve his or her purpose. [citation omitted] The amount that may be used diminishes the less the purpose is to critique the original and the more that the parody serves as a substitute for the original."

So, in other words, the parodist may borrow only the material sufficient to insure the audience gets the joke and no more. Obviously, the Judge thought the Honda Del Sol commercial went over the line, and ruled accordingly.

We do know that the musical Merry Saltzman is planning to present borrows not only the character of Bond, but "several Bond villains" as well.[ref]James Bond Broadway Musical Promises "Our Own Bond Girl" - Exclusive Details Revealed[/ref] Will this be too much? Will the inclusion of "several" Bond villains be allowed where one or two would be sufficient? Does this musical production go so far as to "substitute for the original?" Certainly, the Bonds of the Daniel Craig era have been serious, somber affairs, but the Bonds of the Roger Moore era leaned so heavily on humor that it could easily be said that they were themselves parodies of the Bond character. If the Austin Powers films made 61 separate references to the Bond films, resulting in only one, very specific, legal challenge, there could be a lot of wiggle room here. In any event, hard analysis is difficult at this point since no copy of the proposed play has been leaked.

Two more factors will come into consideration. Will the play impermissibly adopt the "total concept and feel" of the Bond movies as the Judge ruled in American Honda? And we have not even begun to consider whether the new Bond "parody musical" might be found to be a "transformative use" by a friendly court within the jurisdiction of the Second Circuit Court of Appeals.

All that remains is to see who fires the first shot over the man with a "license to kill."

No Subjects

A series of curious events happened in June. Courts across the globe started to take action against those web business that actively service pirate websites. Amongst these actions were:

- On June 11, 2015, the Court of Appeal for British Columbia ruled that Google had to block a rogue website offering counterfeit goods from its search results on a worldwide basis.[ref]Equustek Solutions Inc. v. Google Inc.[/ref]

- On June 3, 2015, the District Court for the Southern District of New York held that CloudFlare, a reverse-proxy service, had violated a preliminary injunction by directing people to pirate websites using the word "grooveshark."[ref]Arista Records, LLC, et al., v. Vita Tkach, et al.[/ref]

- On June 1, 2015, a German appellate Court affirmed a ruling that Google, once on notice of infringing material appearing on YouTube, had an affirmative duty to prevent the material from being reposted.[ref]YouTube not liable on copyright, but needs to do more: German court[/ref]

- In late June, an Australian law requiring ISP to block pirate websites went into effect.[ref]Site blocking bill goes into force in Australia[/ref]

No Subjects

Following on the heels of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals' decision in Garcia v. Google,[ref]Ninth Circuit Reverses "Innocence of Muslims" Ruling, Hollywood Breathes a Sigh of Relief[/ref] the Second Circuit Court of Appeals has issued a major ruling clarifying one of the great mysteries of copyright law, namely: who is the "author" of a motion picture? The Second Circuit's opinion is particularly important because it governs the State of New York, home to many of the largest entertainment companies. So now the Courts of Appeal that govern Hollywood and New York City have both issued ruling on what the copyright in a motion picture covers and who is the author of the film.

The facts of 16 Casa Duse, LLC v. Merkin [ref]2015 WL 3937947 U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, 2015[/ref] are not complicated. A production company known as 16 Casa Duse acquired the rights to a screenplay for a short film entitled Hands Up. It hired all of the cast and crew of about 30 people, including a script supervisor, director of photography, camera operators and significantly enough, director Alex Merkin.[ref]Id. at page 4. Pagination is from the original opinion.[/ref] Everyone in the cast and crew signed their contract with the Producer, except of course, the Director, who never signed his contract. This is significant since the contracts all specified that the contributions by the signer were to be "works made for hire" and thus transfer any copyright interest to the Producer. The film was completed and the Director took into his possession four computer hard drives that contained the raw footage for the film.[ref]Id. at page 6[/ref]

In the inevitable dispute that followed, the Director refused to sign his contract or return the four hard drives containing the raw footage of the film. When the Producer attempted to arrange showings of the film, these were met with threats of a cease and desist order from the Director and his attorney, which caused the film to miss at least four film festival submission deadlines.[ref]Id. at page 9[/ref] Unknown to the Producer, the Director had also registered the raw footage with the Copyright Office and listed the Director as the sole author.[ref]Id. at page 8[/ref]

The District Court issued a preliminary injunction against the Director, ruled that the Producer, not the Director was the author for purposes of copyright, and awarded attorneys fees against both the director and his attorney.[ref]Id. at page 12[/ref]

Curiously, the Director did not claim to be a joint author or co-author of the film.[ref]Id. at page 16[/ref] Presumably, the reason being that if he was, he could not prevent the Producer from exploiting the film on a non-exclusive basis.[ref]Id.[/ref] So, either the Director is the author of all of the film, or none of it. According to the Second Circuit panel, he is the author of none of it.

For the first time, a Court of Appeal had to confront the question of:

"…whether an individual's non-de minimis creative contributions to a work in which copyright protection subsists, such as a film, fall within the subject matter of copyright, when the contributions are inseparable from the work and the individual is neither the sole nor a joint author of the work and is not a party to a work-for-hire arrangement."

The opinion hones in on the fact that the Director's contributions were "inseparable" from the finished product, and that none of the contributions of the Director were separately copyrightable.

"'A motion picture is a work to which many contribute; however, those contributions ultimately merge to create a unitary whole.' But the [Copyright] Act lists none of the constituent parts of any of these kinds of works as ‘works of authorship.' This uniform absence of explicit protection suggests that non-freestanding contributions to works of authorship are not ordinarily themselves works of authorship."[ref]Id. at 20. Citation to quote omitted. [/ref]

So the opinion draws the authorship line as to whether a contribution to a copyrighted motion picture could stand "on its own."

"[A]uthors of freestanding works that are incorporated into a film, such as dance performances or songs, may copyright these ‘separate and independent work[s].' (citation defining "collective work" omitted ). But a director's contribution to an integrated ‘work of authorship' such as a film is not itself a ‘work of authorship' subject to its own copyright protection."[ref]Id. at 25[/ref]

The Court also could have taken a slightly different tack. Motion pictures by their very nature are derivative works from the underlying source material, namely the screenplay. While there may be various artistic decisions being made by a Director, they are naturally guided and shaped by what has already been written, since the end desire is to fully realize the plot and characters present in the script. The script, being the property of the Producer, can only be acted upon by the Director in the nature of creating a derivative work, which requires the permission of the Producer. If that permission is not express, but can be implied, as here, there would be a corresponding implied permission for the Producer to utilize the fruits of the Director's work.

The Court also pointed out a sound policy reason for reaching its decision:

"A conclusion other than the one we adopt would grant contributors like [the Director] greater rights than joint authors, who, as we have noted, have no right to interfere with a co-author's use of the copyrighted work… We doubt that Congress intended for contributors who are not joint authors to have greater rights enabling them to hamstring authors' use of copyrighted works, as apparently occurred in the case at bar. We agree with the en banc Ninth Circuit, then, that the creation of ‘thousands of standalone copyrights' in a given work was likely not intended."[ref]Id.[/ref]

In determining who owned the copyright amongst multiple participants, the court held that "the dispositive inquiry is which of the putative authors is the ‘dominant author,'[ref]Id. at 28[/ref]and enumerated three major factors:

- Who holds the decision making authority

- The manner in which parties credit themselves

- The parties agreements with 3rd parties"[ref]Id.[/ref]

- The Director did not create any independently copyrightable material such as a song, dance or painting, so whatever copyrightable material he created is subsumed in the copyright in the motion picture

- The Director has expressly denied that he is a co-author or joint author of the film, and has no interest in the copyright by reason of joint ownership

- The Producer was the "dominant author" and thus the owner of the copyright in the film.

No Subjects