Two months ago, the Wall Street Journal ran an article reporting that Spotify had failed to pay a significant amount of royalties due to the music publishing company associated with Victory Records.[ref]Songwriters Lose Out on Royalties[/ref] Rather than make nice with Victory Records' publishing arm, Spotify responded by pulling Victory's catalog off the music streaming service.[ref]Amidst Serious Accusations, Spotify Removes Victory Records' Catalog[/ref]

This was immediately followed by several articles by David Lowery, (a songwriter for the indie bands Cracker and Camper Van Beethoven) on his website, The Trichordist. There, he stated that Spotify was playing more than 150 songs of his without permission or payment[ref]Spotify Has Apparently Failed to License, Account and Pay on More than 150 Cracker and Camper Van Beethoven Songs[/ref] and published an open letter to the Attorney General of the State of New York calling for an investigation.[ref]Letter to the New York Attorney General Asking for Investigation of Unpaid Royalties at Spotify and YouTube[/ref]

Spotify responded to these reports in the Wall Street Journal piece by stating:

""We want to pay every penny, but we need to know who to pay," Spotify spokesman Jonathan Prince said in an email. "The industry needs to come together and develop an approach to publishing rights based on transparency and accountability."[ref]Songwriters Lose Out on Royalties[/ref]

The Wall Street Journal article went on to quote Audiam Chief Executive Jeff Price as stating:

"'The problem isn't that they're not setting aside the money, or that they don't want to pay the money,'…[t]he problem is they don't know who wrote the song, or how to find the person to pay them.'"

This certainly piqued my interest. During my 26-year career as an entertainment attorney, I have licensed songs to every major record label in the world. And the record companies in question did not seem to have any trouble locating my clients, or me for that matter. Since my joining Nova Southeastern University, my former clients have been passed on to other attorneys with active law practices, except for one small music publisher with whom I had a close working relationship for over 20 years. They requested that I continue to represent them, and the university was gracious enough to allow this (on an "after hours" basis only, of course).

The music publisher in question administers a catalog of songs composed by an internationally famous musician. Though the catalog is small, it generates a significant amount of revenue every year from a variety of sources. I have never been contacted by anyone from Spotify regarding licenses for any song in this catalog. If Spotify had contacted the client directly, they would have passed the request on to me.

Could it be possible that Spotify was streaming these songs without ever contacting us or paying the client?

I called up my son, who has Spotify, and asked him if this musician was available on Spotify.

"Yeah," he said. "They've got a whole page of him."

I asked him to take a screen shot and email it to me.

I opened up the screen shot and looked at it in disbelief. There, listed amongst his other songs, was a song owned by my clients that had 642,558 streams. To make matters worse, the song had only the one writer, and so was owned 100% by my clients. Therefore, the possibility that a co-writer's publishing company had issued a license did not exist. A quick email to the client publisher's accountant confirmed my suspicions.

Spotify had not paid a penny in royalties.

This is where the whole "we don't know who the songwriters are or where to find them argument" falls flat. Every record company has a department that does nothing but license the musical compositions which appear on their recordings. They know who the songwriters are, what the percentage splits of the copyright are, and most importantly, where to send the royalty payments.

The song in question first appeared on an album 40 years ago, and that album has been continuously available ever since. And every three months the record company sends a royalty check to the publisher. How hard would it have been for Spotify to pick up the phone or shoot an email to the record company (one of the largest in the world, BTW) and ask "how do we get in contact with the publisher for this song?" The publisher has an address which has not changed for years, probably decades. While I moved my office a few times during my active practice years, I have had the same phone number and same email address for the entire length of my practice, and they still work today.

And certainly, Spotify knows who the musician is. His name and picture appear on the Spotify listing. Spotify took the time to set up a page and post a picture to attract listeners but couldn't take the time to properly license the songs?

So, as we dig deeper and deeper, Spotify's excuse of "we don't know where to find people" gets worse and worse.

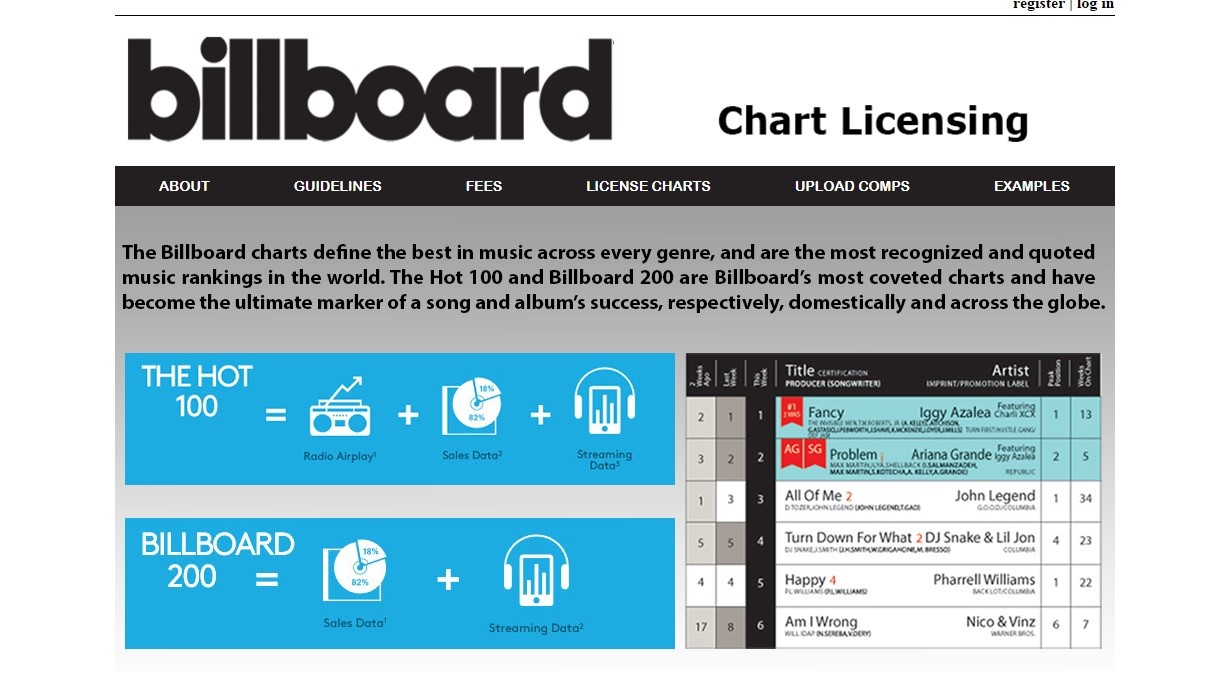

The song in question got sampled or interpolated into new songs quite a few times by R&B and rap artists. On one occasion, the new song was a top ten hit on the Billboard Hot 100 Chart. On another occasion, a different interpolation was on a CD that sold two million copies. And, on a third new use, it was a #1 hit on the Billboard Rap Charts. In each case, there was a written license agreement which detailed who the writers were, what the splits were, and the name, address and tax ID number of my music publisher client. This agreement would still be on file at the offices of the record company that made the recording.

How hard would it have been for Spotify to call or email in order to get this information? And don't forget, Spotify has not paid a penny to my client on these recordings either, two of which were major hits, and of which my client owns a substantial portion of the copyright. On one of these songs, our co-publisher is Universal Music Publishing, one of the largest music publishers in the world. By agreement, they cannot license the song without my client's consent. Universal certainly knows where to find me, and my client.

Also, the composer and the publisher are both affiliated with ASCAP for the purposes of public performances, and always have been. ASCAP sends checks four times a year for domestic performances and twice a year for foreign performances. ASCAP certainly knows where to find us, and what songs we control. How hard would have been to ask ASCAP for the publisher contact information?

Here's a final tip for Spotify: If you subscribe to the Billboard Hot 100 Chart, they include who the writer is and who the record company is for each song on the chart.

It just so happened that, in recent months, the record company who first released the song was issuing some retrospective releases regarding the musician and various bands he had been in. So I emailed them to get a contact at Spotify with whom I could get this issue resolved. They did, and when I contacted Spotify, the response was immediate and polite. "Thanks for reaching out to us," the email read in part, which again, is polite but beside the point. Spotify should have reached out to us quite a while ago.

It turns out that Spotify has engaged the Harry Fox Agency to facilitate their payments to music publishers. Anyone involved in the music industry already knows who the HFA is, but for those readers who are unfamiliar, suffice it to say, they are perhaps the largest independent broker of music rights in the U.S.[ref]The Harry Fox Agency, Inc.[/ref] Usually, the HFA charges a fee to the publisher to issue licenses on their behalf, but in this case, the HFA representative I corresponded and spoke with informed me that Spotify pays all the charges associated with their licenses. That's a good start.

The HFA representative (who was very nice and I have no problem with) told me that Spotify would pay all of the back royalties on all the songs in which the publisher had an ownership interest, provided that we provide them with a list of songs and the splits. Not a problem. After the back payments were made, Spotify would pay royalties on a monthly basis. That's a plus.

That's sort of where the good news ends. Spotify would only agree to pay the same crummy rate they pay everyone else. The royalty rate is a "blended rate" the average of which is $0.00043 per spin. That's 4/100th of a cent. So, multiplied by the 642,558 streams, the grand total (for that song only) is $276.29. HFA/Spotify also would not agree to move my client's songs exclusively to the pay tier, so as to get an improved royalty rate. That's reserved for the Taylor Swifts of this world.

All of this, despite the fact that Spotify has already infringed my client's copyright 642,558 times. On one song.

Consider that Spotify, as an "on demand" streaming service, cannot rely on blanket licenses for regular web streaming, the rates for which are set by the Copyright Royalty Board.[ref]D.C. Sets New Webcasting Rates: Free Streams Up, Paid Streams Down (With an Asterisk)[/ref] They have to have a license for each and every song that they play. But, clearly they, do not have such licenses, but play the songs anyway.

The HFA representative insisted that there was no real business advantage to Spotify's method as the unpaid royalties were escrowed until the publisher could be located, and then all the back royalties were paid out. Fair enough. But is the account where all these funds are being kept an interest bearing account? And if so, who is getting the interest? Unfortunately, my HFA representative did not know the answer. Suffice it to say, an account which probably contains millions of dollars and bears interest would confer a huge revenue boost to Spotify, and might go a long way towards explaining why they are unenthusiastic about locating the publishers of the music that they stream.

What is particularly grating is the attitude replete through the tech industries that obeying the law is either an afterthought, or something to be totally disregarded. Starting with Napster, through Aimster, Grokster, LimeWire, BitTorrent, Grooveshark and more recently Cox Communications,[ref]14 Strikes and You're Out! (Maybe): How Cox Communications Lost its DMCA Safe Harbor[/ref] tech companies frequently operate as if the law does not apply to them. This attitude spills over into other tech companies, like Uber and Airbnb, who find that an effective way of competing is to simply not obey the laws and regulations that govern their competitors in the taxi and lodging industries.

Go back to the quote at the top of the post:

"The industry needs to come together and develop an approach to publishing rights based on transparency and accountability."[ref]Songwriters Lose Out on Royalties[/ref]

In other words, Spotify thinks it's the publisher's fault they can't find us, and thinks it's the publisher's responsibility to spend the money necessary to fix it, which of course has the corollary effect of increasing their revenue.

Baloney. And totally backwards.

That's not the way it works, and has never been the way it works. You don't use someone's copyright until you have the right to do so. Licensing is your responsibility, Spotify. If you don't have a license, don't stream it. It's really that simple. Don't get into the music business if you have no clue how the music business works. Record companies have full-time licensing departments. Why don't you?

Plus, there are, right now, huge searchable databases of musical compositions, their composers and their respective publishers. They are run by ASCAP, BMI and SESAC. The problem is that the U.S. Department of Justice enforces consent decrees that legally prevent ASCAP and BMI from issuing the very kind of licenses Spotify wants. The Registrar of Copyrights has proposed removing those restrictions.[ref]The Copyright Office's Music Licensing Report Explained! (Hopefully)[/ref] That might be a good first step.

So, meanwhile, my client mulls its options.

Could we demand that Spotify remove the client's catalog? Sure, but that would not necessarily remove songs on which there is a co-author and co-publisher, who might have granted a license.

Could a copyright infringement suit be filed? Sure. And a slam dunk case at that. But the client would spend a lot of money (Federal Court is very expensive) arguing with Spotify about what the proper level of damages would be, and then perhaps defending an appeal of that judgement. Plus, given Spotify's very shaky finances,[ref]More Money, No Profit: Is the "Free For All" Ethos of the Internet Killing Streaming?[/ref] would a judgement even be collectable by the time it became final?

And finally, as a small publisher, or me as their agent, it is absolutely ridiculous to expect us to police the entire worldwide internet 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year. The time has come to put the burden back on the people who profit from using our property, and end this attitude of "we'll get around to it when we feel like, if at all."

It just so happened that, in recent months, the record company who first released the song was issuing some retrospective releases regarding the musician and various bands he had been in. So I emailed them to get a contact at Spotify with whom I could get this issue resolved. They did, and when I contacted Spotify, the response was immediate and polite. "Thanks for reaching out to us," the email read in part, which again, is polite but beside the point. Spotify should have reached out to us quite a while ago.

It turns out that Spotify has engaged the Harry Fox Agency to facilitate their payments to music publishers. Anyone involved in the music industry already knows who the HFA is, but for those readers who are unfamiliar, suffice it to say, they are perhaps the largest independent broker of music rights in the U.S.[ref]The Harry Fox Agency, Inc.[/ref] Usually, the HFA charges a fee to the publisher to issue licenses on their behalf, but in this case, the HFA representative I corresponded and spoke with informed me that Spotify pays all the charges associated with their licenses. That's a good start.

The HFA representative (who was very nice and I have no problem with) told me that Spotify would pay all of the back royalties on all the songs in which the publisher had an ownership interest, provided that we provide them with a list of songs and the splits. Not a problem. After the back payments were made, Spotify would pay royalties on a monthly basis. That's a plus.

That's sort of where the good news ends. Spotify would only agree to pay the same crummy rate they pay everyone else. The royalty rate is a "blended rate" the average of which is $0.00043 per spin. That's 4/100th of a cent. So, multiplied by the 642,558 streams, the grand total (for that song only) is $276.29. HFA/Spotify also would not agree to move my client's songs exclusively to the pay tier, so as to get an improved royalty rate. That's reserved for the Taylor Swifts of this world.

All of this, despite the fact that Spotify has already infringed my client's copyright 642,558 times. On one song.

Consider that Spotify, as an "on demand" streaming service, cannot rely on blanket licenses for regular web streaming, the rates for which are set by the Copyright Royalty Board.[ref]D.C. Sets New Webcasting Rates: Free Streams Up, Paid Streams Down (With an Asterisk)[/ref] They have to have a license for each and every song that they play. But, clearly they, do not have such licenses, but play the songs anyway.

The HFA representative insisted that there was no real business advantage to Spotify's method as the unpaid royalties were escrowed until the publisher could be located, and then all the back royalties were paid out. Fair enough. But is the account where all these funds are being kept an interest bearing account? And if so, who is getting the interest? Unfortunately, my HFA representative did not know the answer. Suffice it to say, an account which probably contains millions of dollars and bears interest would confer a huge revenue boost to Spotify, and might go a long way towards explaining why they are unenthusiastic about locating the publishers of the music that they stream.

What is particularly grating is the attitude replete through the tech industries that obeying the law is either an afterthought, or something to be totally disregarded. Starting with Napster, through Aimster, Grokster, LimeWire, BitTorrent, Grooveshark and more recently Cox Communications,[ref]14 Strikes and You're Out! (Maybe): How Cox Communications Lost its DMCA Safe Harbor[/ref] tech companies frequently operate as if the law does not apply to them. This attitude spills over into other tech companies, like Uber and Airbnb, who find that an effective way of competing is to simply not obey the laws and regulations that govern their competitors in the taxi and lodging industries.

Go back to the quote at the top of the post:

"The industry needs to come together and develop an approach to publishing rights based on transparency and accountability."[ref]Songwriters Lose Out on Royalties[/ref]

In other words, Spotify thinks it's the publisher's fault they can't find us, and thinks it's the publisher's responsibility to spend the money necessary to fix it, which of course has the corollary effect of increasing their revenue.

Baloney. And totally backwards.

That's not the way it works, and has never been the way it works. You don't use someone's copyright until you have the right to do so. Licensing is your responsibility, Spotify. If you don't have a license, don't stream it. It's really that simple. Don't get into the music business if you have no clue how the music business works. Record companies have full-time licensing departments. Why don't you?

Plus, there are, right now, huge searchable databases of musical compositions, their composers and their respective publishers. They are run by ASCAP, BMI and SESAC. The problem is that the U.S. Department of Justice enforces consent decrees that legally prevent ASCAP and BMI from issuing the very kind of licenses Spotify wants. The Registrar of Copyrights has proposed removing those restrictions.[ref]The Copyright Office's Music Licensing Report Explained! (Hopefully)[/ref] That might be a good first step.

So, meanwhile, my client mulls its options.

Could we demand that Spotify remove the client's catalog? Sure, but that would not necessarily remove songs on which there is a co-author and co-publisher, who might have granted a license.

Could a copyright infringement suit be filed? Sure. And a slam dunk case at that. But the client would spend a lot of money (Federal Court is very expensive) arguing with Spotify about what the proper level of damages would be, and then perhaps defending an appeal of that judgement. Plus, given Spotify's very shaky finances,[ref]More Money, No Profit: Is the "Free For All" Ethos of the Internet Killing Streaming?[/ref] would a judgement even be collectable by the time it became final?

And finally, as a small publisher, or me as their agent, it is absolutely ridiculous to expect us to police the entire worldwide internet 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year. The time has come to put the burden back on the people who profit from using our property, and end this attitude of "we'll get around to it when we feel like, if at all."

It just so happened that, in recent months, the record company who first released the song was issuing some retrospective releases regarding the musician and various bands he had been in. So I emailed them to get a contact at Spotify with whom I could get this issue resolved. They did, and when I contacted Spotify, the response was immediate and polite. "Thanks for reaching out to us," the email read in part, which again, is polite but beside the point. Spotify should have reached out to us quite a while ago.

It turns out that Spotify has engaged the Harry Fox Agency to facilitate their payments to music publishers. Anyone involved in the music industry already knows who the HFA is, but for those readers who are unfamiliar, suffice it to say, they are perhaps the largest independent broker of music rights in the U.S.[ref]The Harry Fox Agency, Inc.[/ref] Usually, the HFA charges a fee to the publisher to issue licenses on their behalf, but in this case, the HFA representative I corresponded and spoke with informed me that Spotify pays all the charges associated with their licenses. That's a good start.

The HFA representative (who was very nice and I have no problem with) told me that Spotify would pay all of the back royalties on all the songs in which the publisher had an ownership interest, provided that we provide them with a list of songs and the splits. Not a problem. After the back payments were made, Spotify would pay royalties on a monthly basis. That's a plus.

That's sort of where the good news ends. Spotify would only agree to pay the same crummy rate they pay everyone else. The royalty rate is a "blended rate" the average of which is $0.00043 per spin. That's 4/100th of a cent. So, multiplied by the 642,558 streams, the grand total (for that song only) is $276.29. HFA/Spotify also would not agree to move my client's songs exclusively to the pay tier, so as to get an improved royalty rate. That's reserved for the Taylor Swifts of this world.

All of this, despite the fact that Spotify has already infringed my client's copyright 642,558 times. On one song.

Consider that Spotify, as an "on demand" streaming service, cannot rely on blanket licenses for regular web streaming, the rates for which are set by the Copyright Royalty Board.[ref]D.C. Sets New Webcasting Rates: Free Streams Up, Paid Streams Down (With an Asterisk)[/ref] They have to have a license for each and every song that they play. But, clearly they, do not have such licenses, but play the songs anyway.

The HFA representative insisted that there was no real business advantage to Spotify's method as the unpaid royalties were escrowed until the publisher could be located, and then all the back royalties were paid out. Fair enough. But is the account where all these funds are being kept an interest bearing account? And if so, who is getting the interest? Unfortunately, my HFA representative did not know the answer. Suffice it to say, an account which probably contains millions of dollars and bears interest would confer a huge revenue boost to Spotify, and might go a long way towards explaining why they are unenthusiastic about locating the publishers of the music that they stream.

What is particularly grating is the attitude replete through the tech industries that obeying the law is either an afterthought, or something to be totally disregarded. Starting with Napster, through Aimster, Grokster, LimeWire, BitTorrent, Grooveshark and more recently Cox Communications,[ref]14 Strikes and You're Out! (Maybe): How Cox Communications Lost its DMCA Safe Harbor[/ref] tech companies frequently operate as if the law does not apply to them. This attitude spills over into other tech companies, like Uber and Airbnb, who find that an effective way of competing is to simply not obey the laws and regulations that govern their competitors in the taxi and lodging industries.

Go back to the quote at the top of the post:

"The industry needs to come together and develop an approach to publishing rights based on transparency and accountability."[ref]Songwriters Lose Out on Royalties[/ref]

In other words, Spotify thinks it's the publisher's fault they can't find us, and thinks it's the publisher's responsibility to spend the money necessary to fix it, which of course has the corollary effect of increasing their revenue.

Baloney. And totally backwards.

That's not the way it works, and has never been the way it works. You don't use someone's copyright until you have the right to do so. Licensing is your responsibility, Spotify. If you don't have a license, don't stream it. It's really that simple. Don't get into the music business if you have no clue how the music business works. Record companies have full-time licensing departments. Why don't you?

Plus, there are, right now, huge searchable databases of musical compositions, their composers and their respective publishers. They are run by ASCAP, BMI and SESAC. The problem is that the U.S. Department of Justice enforces consent decrees that legally prevent ASCAP and BMI from issuing the very kind of licenses Spotify wants. The Registrar of Copyrights has proposed removing those restrictions.[ref]The Copyright Office's Music Licensing Report Explained! (Hopefully)[/ref] That might be a good first step.

So, meanwhile, my client mulls its options.

Could we demand that Spotify remove the client's catalog? Sure, but that would not necessarily remove songs on which there is a co-author and co-publisher, who might have granted a license.

Could a copyright infringement suit be filed? Sure. And a slam dunk case at that. But the client would spend a lot of money (Federal Court is very expensive) arguing with Spotify about what the proper level of damages would be, and then perhaps defending an appeal of that judgement. Plus, given Spotify's very shaky finances,[ref]More Money, No Profit: Is the "Free For All" Ethos of the Internet Killing Streaming?[/ref] would a judgement even be collectable by the time it became final?

And finally, as a small publisher, or me as their agent, it is absolutely ridiculous to expect us to police the entire worldwide internet 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year. The time has come to put the burden back on the people who profit from using our property, and end this attitude of "we'll get around to it when we feel like, if at all."

It just so happened that, in recent months, the record company who first released the song was issuing some retrospective releases regarding the musician and various bands he had been in. So I emailed them to get a contact at Spotify with whom I could get this issue resolved. They did, and when I contacted Spotify, the response was immediate and polite. "Thanks for reaching out to us," the email read in part, which again, is polite but beside the point. Spotify should have reached out to us quite a while ago.

It turns out that Spotify has engaged the Harry Fox Agency to facilitate their payments to music publishers. Anyone involved in the music industry already knows who the HFA is, but for those readers who are unfamiliar, suffice it to say, they are perhaps the largest independent broker of music rights in the U.S.[ref]The Harry Fox Agency, Inc.[/ref] Usually, the HFA charges a fee to the publisher to issue licenses on their behalf, but in this case, the HFA representative I corresponded and spoke with informed me that Spotify pays all the charges associated with their licenses. That's a good start.

The HFA representative (who was very nice and I have no problem with) told me that Spotify would pay all of the back royalties on all the songs in which the publisher had an ownership interest, provided that we provide them with a list of songs and the splits. Not a problem. After the back payments were made, Spotify would pay royalties on a monthly basis. That's a plus.

That's sort of where the good news ends. Spotify would only agree to pay the same crummy rate they pay everyone else. The royalty rate is a "blended rate" the average of which is $0.00043 per spin. That's 4/100th of a cent. So, multiplied by the 642,558 streams, the grand total (for that song only) is $276.29. HFA/Spotify also would not agree to move my client's songs exclusively to the pay tier, so as to get an improved royalty rate. That's reserved for the Taylor Swifts of this world.

All of this, despite the fact that Spotify has already infringed my client's copyright 642,558 times. On one song.

Consider that Spotify, as an "on demand" streaming service, cannot rely on blanket licenses for regular web streaming, the rates for which are set by the Copyright Royalty Board.[ref]D.C. Sets New Webcasting Rates: Free Streams Up, Paid Streams Down (With an Asterisk)[/ref] They have to have a license for each and every song that they play. But, clearly they, do not have such licenses, but play the songs anyway.

The HFA representative insisted that there was no real business advantage to Spotify's method as the unpaid royalties were escrowed until the publisher could be located, and then all the back royalties were paid out. Fair enough. But is the account where all these funds are being kept an interest bearing account? And if so, who is getting the interest? Unfortunately, my HFA representative did not know the answer. Suffice it to say, an account which probably contains millions of dollars and bears interest would confer a huge revenue boost to Spotify, and might go a long way towards explaining why they are unenthusiastic about locating the publishers of the music that they stream.

What is particularly grating is the attitude replete through the tech industries that obeying the law is either an afterthought, or something to be totally disregarded. Starting with Napster, through Aimster, Grokster, LimeWire, BitTorrent, Grooveshark and more recently Cox Communications,[ref]14 Strikes and You're Out! (Maybe): How Cox Communications Lost its DMCA Safe Harbor[/ref] tech companies frequently operate as if the law does not apply to them. This attitude spills over into other tech companies, like Uber and Airbnb, who find that an effective way of competing is to simply not obey the laws and regulations that govern their competitors in the taxi and lodging industries.

Go back to the quote at the top of the post:

"The industry needs to come together and develop an approach to publishing rights based on transparency and accountability."[ref]Songwriters Lose Out on Royalties[/ref]

In other words, Spotify thinks it's the publisher's fault they can't find us, and thinks it's the publisher's responsibility to spend the money necessary to fix it, which of course has the corollary effect of increasing their revenue.

Baloney. And totally backwards.

That's not the way it works, and has never been the way it works. You don't use someone's copyright until you have the right to do so. Licensing is your responsibility, Spotify. If you don't have a license, don't stream it. It's really that simple. Don't get into the music business if you have no clue how the music business works. Record companies have full-time licensing departments. Why don't you?

Plus, there are, right now, huge searchable databases of musical compositions, their composers and their respective publishers. They are run by ASCAP, BMI and SESAC. The problem is that the U.S. Department of Justice enforces consent decrees that legally prevent ASCAP and BMI from issuing the very kind of licenses Spotify wants. The Registrar of Copyrights has proposed removing those restrictions.[ref]The Copyright Office's Music Licensing Report Explained! (Hopefully)[/ref] That might be a good first step.

So, meanwhile, my client mulls its options.

Could we demand that Spotify remove the client's catalog? Sure, but that would not necessarily remove songs on which there is a co-author and co-publisher, who might have granted a license.

Could a copyright infringement suit be filed? Sure. And a slam dunk case at that. But the client would spend a lot of money (Federal Court is very expensive) arguing with Spotify about what the proper level of damages would be, and then perhaps defending an appeal of that judgement. Plus, given Spotify's very shaky finances,[ref]More Money, No Profit: Is the "Free For All" Ethos of the Internet Killing Streaming?[/ref] would a judgement even be collectable by the time it became final?

And finally, as a small publisher, or me as their agent, it is absolutely ridiculous to expect us to police the entire worldwide internet 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year. The time has come to put the burden back on the people who profit from using our property, and end this attitude of "we'll get around to it when we feel like, if at all."