- We think the decision below is correct.

- We think the decision below is incorrect, but we have more important issues to decide.

- We think the issue is important, but this case does not lend itself to a complete consideration or resolution of the issue.

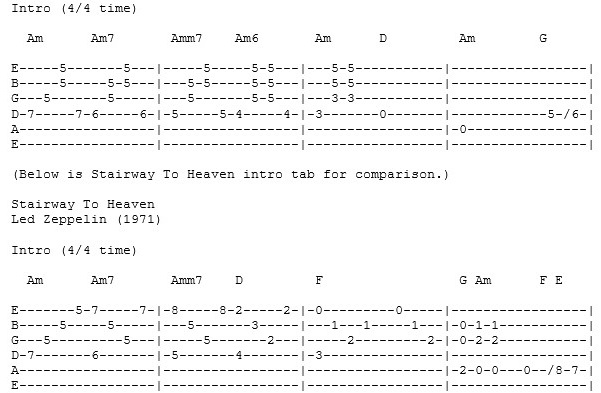

In other words, "Taurus" was not the only source from which the melody could have emanated. Jimmy Page could have composed "Stairway to Heaven" without reference to either "Taurus" or "Cry Me a River," because it uses fairly standard techniques and harmonic progressions.

As a songwriter myself, I can assure you that composing is a mysterious process, in which the brain guides you in both conscious and unconscious ways. It is very possible that Jimmy Page had heard "Taurus" or "Cry Me a River" (or both) and simply did not remember it when composing "Stairway to Heaven." As George Harrison found out, it's still copyright infringement, even if done unintentionally and subconsciously.[ref]Bright Tunes Music Corp. v. Harrisongs Music, Ltd. 420 F.Supp. 177 United States District Court, S. D. New York. (1976)[/ref]

The Harrison case is further worth noting in that it shows us what substantial similarity really is. Taken side by side, it is clear that they are the same song with different lyrics.

https://youtu.be/sYiEesMbe2I

I cannot say, in my experience, that the same is true for "Taurus" and "Stairway to Heaven."

I have been wrong before, the "Blurred Lines" case being the most recent example.[ref]The "Blurred Lines" Verdict: What It Means For Music Now and In the Future[/ref] Yet, as I discussed that verdict with an old attorney friend, and fellow musician, we both uttered the same thought at nearly the same time…

"Gosh, there are only 12 notes in an octave to choose from."

Given that limited a palette to paint from, similarities are bound to occur.

In other words, "Taurus" was not the only source from which the melody could have emanated. Jimmy Page could have composed "Stairway to Heaven" without reference to either "Taurus" or "Cry Me a River," because it uses fairly standard techniques and harmonic progressions.

As a songwriter myself, I can assure you that composing is a mysterious process, in which the brain guides you in both conscious and unconscious ways. It is very possible that Jimmy Page had heard "Taurus" or "Cry Me a River" (or both) and simply did not remember it when composing "Stairway to Heaven." As George Harrison found out, it's still copyright infringement, even if done unintentionally and subconsciously.[ref]Bright Tunes Music Corp. v. Harrisongs Music, Ltd. 420 F.Supp. 177 United States District Court, S. D. New York. (1976)[/ref]

The Harrison case is further worth noting in that it shows us what substantial similarity really is. Taken side by side, it is clear that they are the same song with different lyrics.

https://youtu.be/sYiEesMbe2I

I cannot say, in my experience, that the same is true for "Taurus" and "Stairway to Heaven."

I have been wrong before, the "Blurred Lines" case being the most recent example.[ref]The "Blurred Lines" Verdict: What It Means For Music Now and In the Future[/ref] Yet, as I discussed that verdict with an old attorney friend, and fellow musician, we both uttered the same thought at nearly the same time…

"Gosh, there are only 12 notes in an octave to choose from."

Given that limited a palette to paint from, similarities are bound to occur.On March 29, 2016, a huge study on the volume and effectiveness of DMCA take downs was published. 1 Titled “Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice,” the authors made some rather stunning assertions which were widely reported in the news media. For example, as reported by this web blog, was the fact that “[a]lmost 30 percent of all piracy takedown requests are problematic.” 2

There’s only one problem. This “fact” is not true. Anyone who had actually taken the time to read the study would know it’s not true. The study only examined those notices sent to Lumens (formerly known as Chilling Effects) which are predominantly those directed to Google. To quote directly from the report:

“The dominance of Google notices in our dataset limits our ability to draw broader conclusions about the notice ecosystem…Google’s dominant position in search and the extraordinary number of notices it receives also make it unusual. This makes the Lumen dataset useful for studying an important part of the takedown system, but also means that the characteristics of these notices cannot be extrapolated to the entire world of notice sending.” 3

What really followed was a rather stunning failure of journalists across the country to read at all, much less with a critical eye, a Google funded study 4 that has fundamental flaws and exhibits a rather slanted viewpoint.

The study reaches the conclusion that the majority of faulty takedown notices are generated by small and individual copyright holders, not “professional content companies.” 5

The central problem is that the study lumps together takedown notices with mere clerical errors with those that might be abusive, and seeks to tar them all with the same brush. This leads to their rather curious assertion that a multi-billion dollar company like Google needs better legal protection from small copyright owners and individual artists. What they propose is the creation of brand new draconian legal penalties to be assessed against those small and individual copyright owners for the crime of making a clerical error. 6

At 147 pages, it’s a lot to digest. I’ve gone through it so many times I wore out two highlighters and my copy has so many sticky notes pasted to it, it looks like a peacock. So in case you don’t have the time, I’ve included the quick hit points. But the beauty of a blog is that I have no space constraints, so I can dig a lot deeper than a 500 word article. For those who are interested, a more detailed analysis follows the bullet points.

Here are the highlights, or should I say lowlights?

- Google funded the report. 7

- Google funded other projects by the participants. 8

- The study directly adopts several recommendations from Public Knowledge, 9 also funded by Google. 10

- The other Google funded projects include those in which the participants align themselves with the extremist Electronic Frontier Foundation, 11 which has itself received over $1 million dollars in funding from Google. 12

- Recommends five specific legal reforms, all of which increase burdens and penalties on persons sending takedown notices and suggests no proposals which increase burdens, responsibilities or liabilities for Online Service Providers. 13

- Fails to consider how “whack-a-mole” contributes to the overall volume of takedown notices, and provides no suggestions for curbing the problem. As near as I can tell, the entire “whack-a-mole” problem receives less than one full page of discussion in the 147 page report. 14

- The study fails to factually reconcile it’s assertion of 30% “bad” notices rate against Google’s own transparency report which shows a positive compliance rate of 97% of all takedown notices received. 15

- The study flatly states certain types of works “weight favorably towards fair use” without citing a single court case which found these types of works were in fact “fair use.” 16

- Did not actually perform a full fair use analysis on any of the files it contended were fair use. 17

- The study did not (as reported) review 108 million 18 or even 100 million takedown notices. 19 The actual number reviewed by the study was 1,826 20 sent to Google generally and 1,732 sent to Google Images. 21

- In the Google Images subset, almost 80% of the notices were sent by persons outside the United States 22 and 52.9% were sent by a single individual, 23 a lady in Sweden, who very well may be off her rocker. 24

- Fails to consider how Google’s deliberately obtuse and obstructionist takedown form/process might contribute to errors in takedown notices, 25 while contending that misidentification of the infringing work appears to be the major source of faulty takedown notices. 26

- Contends that there are no significant barriers to individuals and small companies using the takedown system because the maybe-crazy lady in Sweden is capable of sending out a whole bunch of notices. (Seriously) 27

- Failed to interview any small business or individual copyright holders who sent takedown notices to find out why or how problems occur. 28

- Failed to interview a single person who had either been the “target” of a notice or filed a counter-notice. 29

- Despite not interviewing even one “target” of a takedown notice, the study contends that the counter-notice provisions are “ineffective, empowering unscrupulous users and subjecting legitimate ones to legal jeopardy. Targets were widely considered to lack sufficient information to respond to mistaken or abusive notices.” 30

- The section headed “Repeat Infringer Policies and ‘Strikes’” fails to mention even once the Grooveshark case 31 or the Cox Communications case, 32 despite the fact that the failure to terminate repeat infringers were central to the Court’s ruling in each case.

- Devotes a page and half to a pseudonymously identified web site “struggling” with a flood of DMCA notices, 33 while failing to engage in equivalent scrutiny with web sites like MegaUpload and Grooveshark, which despite receiving hundreds of thousands of legitimate notices, made DMCA non-compliance a part of their business model.

- Devotes two pages to giving examples of mistaken ID in takedown notices. 34 By contrast, independent musician and composer Maria Schnieder’s passionate testimony before Congress about how the need to send out repetitive notices for the same files is ruining her business is dismissed in a footnote. 35

- Throughout the study, makes no distinction between takedown notices with bad information and an abusive takedown notice.

If you’re satisfied with the box score, then thanks for reading and be on your way. If you want something a little more meaty to chew on, then pull up a chair beside me and let’s get at it.

Birds of a Feather Flock Together

Let’s start at the top. Copied into the endnote are six web posts that covered the release of the study. These news outlets include the Washington Post, Variety and CNBC. 36 Not one of them reported that Google funded the study. It’s really hard to miss this point. It’s in the preface to the report.

“This work would not have been possible without both data and funding resources for the coding effort… We are grateful for funding support from Google Inc. as a gift to The American Assembly…” 37

So Google funded the creation of the study, but it doesn’t stop there. Google also donated funds to the Takedown Project run by the American Assembly which employs one of the studies’ co-authors. 38 The two other co-authors are employed by the Berkeley Law School’s Samuelson Law Technology & Public Policy Center, which is one of the main partners in “Chilling Effects,” (now Lumens) 39 along with (surprise) The Electronic Frontier Foundation which has received more than $1 million dollars from Google. 40 And finally, the study directly adopts several recommendations from Public Knowledge, 41 also funded by Google. 42 Kind of cozy wouldn’t you say?

Now, the authors of the survey state that “[n]either funder directed our approach in any way, and neither funder reviewed any methods, data, results, or reporting before public release.” 43 I have no doubt that this is the case. But there’s also a saying that “birds of a feather flock together.”

So the fact that Google had no review or editorial power over the study does not appear to matter much. The author’s assertions and legal positions line up favorably with the interests of Google and the online service providers (OSP’s), and it shows throughout the study.

Here’s a good example. In a footnote devoted to filmmaker Ellen Siedler’s attempt to get her takedown notice taken off Chilling Effects, 44 the study could have linked to her original blog post found here:

http://voxindie.org/i-sent-chilling-effects-a-dmca-takedown-notice/

Instead, the study linked to a post at Tech Dirt which ridiculed her, calling her efforts “stupidity” and posits “Ellen Seidler — anti-piracy activist and tilter at windmills — continues down the road to irrelevance with her latest post…” 45

That the authors would choose to cite to a highly critical blog post that spews insults instead of linking to the author’s firsthand account speaks volumes. Birds of a feather…

And it goes a long way to explain how a 147 page report could come to the conclusion that a multi-billion dollar corporation like Google needs more legal protection from small businesses and individual artists trying desperately to protect their livelihood.

The Actual Numbers Could Be Off by Millions, and One Person Sent 52.9% of the Notices

Here are some more things that were reported about the study which are simply not true, and could have been corrected if the persons involved had simply read the study.

“[T]he researchers reviewed more than 108 million takedown requests and found that 28.4 percent “… had characteristics that raised clear questions about their validity.” 46

“Yet, according to the researchers’ detailed look at a database of more than 100 million requests, incorrect takedowns like those are frequently made and sometimes enforced. That’s a big problem for the Digital Millennium Copyright Act procedures that are often considered the legal backbone of the Internet.” 47

“Using data Google provides to the Lumen database, the researchers reviewed the accuracy of more than 108 million takedown requests.” 48

None of these statements are true.

That’s because the real number of takedowns reviewed is not 108 million or even 100 million.

The real number is 1,826. 49

This is because the researchers used a randomized selection process to create a statistical sample. 50 You can note from the endnote that this fact is revealed on page 1 of the study.

There is nothing wrong or inherently flawed about this approach. I am not a statistician, but in playing with several “statistical sample” generators I have confirmed that you can indeed generate results for 110 million instances from a sample as small as 1,800. But as with any statistical sample, the results are subject to error. The study itself admits that given the large set of the entire database, their results could be off by as much as 7 million instances. 51

Further, the sample was populated using random generators. The problem with random is that it’s, well, random. There is no guarantee that the random selection process will not generate skewed and unrepresentative results. This happened in the sample for notices sent to Google Images. It seems that one person had sent 52.9% of all of the notices. 52 According to the study, this one person (a lady in Sweden), sent notices complaining about material that she alleged “is defamatory, harassing, slanderous or threatening.” 53 In other words, this lady doesn’t know what she is doing and might be off her rocker. Yet, instead of realizing that the random generator has given them a bad data set, and they should try again, the researchers plow on ahead.

The Study Ignores the Effect of Whack-A-Mole

As I plowed through this 147 pages study, I kept asking myself “when are they going to address the issue of whack-a-mole?” (the need to send repetitive notices for the same infringing material). The answer is that the whack-a-mole problem is virtually ignored. This is a trend amongst tech companies and their supporters who seem to think that if the whole whack-a-mole problem is ignored, then maybe it will just go away. Here, the study follows the lead of the EFF, who, when directly confronted with a question regarding whack-a-mole, ignored it and pretended that it did not exist.

The EFF filed comments with the Copyright Office with regards to Section 512 takedowns. In the notice, the Copyright Office specifically asked for a response to this question:

- Does the notice-and-takedown process sufficiently address the reappearance of infringing material previously removed by a service provider in response to a notice? If not, what should be done to address this concern?

The EFF completely ducked this question, going from question #9 to question #12. 54

There can be no question that the need to send out repetitive notices greatly increases the total number of notices sent, and increases the need for automated bots to seek out the material. It is very simple for a bot to determine if a file is the same file which has been subject to a previous takedown notice. It can scan it in seconds. A human would have to watch the entire movie or TV show to determine if it was exactly the same.

The main complaint of the study is:

“The increased use of automated systems by large rightsholders, as well as DMCA Auto and DMCA Plus OSPs, however, raised questions of accuracy and due process. Though rightsholders and OSPs generally use some accuracy checks today, we identified a clear need for better mechanisms to check the accuracy of algorithms, more consistent human review, and a willingness by both rightsholders and OSPs to develop the capacity to identify and reject inappropriate takedown requests.” 55

So, let’s reduce the number of problem notices by reducing the number of total notices that need to be sent. If protections are agreed upon by both parties, and are put in place to help eliminate repeat infringements, this would reduce the total number of notices, and therefore total number of problem notices. As is typical for this study, these contrary facts are ignored, even when they are presented in their own paper.

“In 2011, five of the major ISPs announced a deal with several rightsholders groups to adopt and standardize procedures for warning and—after some number of warning notices—sanctioning repeat infringers… For some ISPs, this has also mitigated the floods of DMCA notices they were receiving before the agreement. According to several respondents, participating ISPs no longer receive DMCA notices from the Motion Picture Association of America (“MPAA”), RIAA, and their partnering groups. One ISP respondent described the agreement as superseding section 512 and generally reducing the number of headaches associated with managing notices. “Going from 1 million to around 100,000 notices per year, he observed, makes a big difference.” 56

Gosh, going from over 1 million notices to 100,000. Sounds like a good idea that should be pursued, right?

Nope. On page 122, the study spends an entire page discussing such voluntary agreements without once suggesting these agreements work and that this might be a good idea.

Just Because You Say It’s Fair Use Doesn’t Make It So

This is where the ideological alignment with tech interests really starts to show up. The study states that it concluded that 7.3% of the takedowns were “flagged with characteristics that weighed favorably towards fair use.” 57 What do the study authors consider “fair use?” “Mashups, remixes or covers.” 58 This is not an accurate statement of existing law. Mashup and remixes are presumptively derivative works under Section 106(2) and would require permission. A cover version under section 115 absolutely requires a license.

In the post-“transformative use” era, the 2nd, 7th, 9th and 11th Circuit Courts of Appeal have all weighed in on fair use, and none of these cases involved remixes, mash-ups or cover versions. 59 In fact, in the one case which most closely resembles a “mash-up,” the case of The Cat Not In the Hat, the 9th Circuit affirmed a finding that the book was copyright infringement and not fair use. 60

Further, this expansive view of mash-ups and remixes as fair use has been severely questioned by the Courts.

In particular, the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals stated “[w]e’re skeptical of [the second Circuit’s]…approach, because asking exclusively whether something is “transformative” not only replaces the list in § 107 but also could override 17 U.S.C. § 106(2), which protects derivative works. To say that a new use transforms the work is precisely to say that it is derivative and thus, one might suppose, protected under § 106(2). Cariou and its predecessors in the Second Circuit do no tex-plain [sic] how every “transformative use” can be “fair use” without extinguishing the author’s rights under § 106(2). We think it best to stick with the statutory list.” 61

Let’s see a quick show of hands from all those making mash-ups and remixes who can recite the four factors of fair use from Section 107, and explain how to apply them correctly. Anybody?

The study could have asked them, but they didn’t. As a matter of fact, they did not interview one single person who was a “target” of a takedown. 62

And if they did, they would find that the understanding of these posters about what constitutes fair use is close to zero. Jonathan Bailey over at Plagiarism Today 63 found this exchange from a poster at Reddit, from an attorney trying to help with fair use claims:

“VideoGameAttorney here to answer questions about fair use, copyright, or whatever the heck else you want to know!”

“I’ve received over 700 emails this past week alone from content creators. I’m truly trying to help everyone I can, but it became overwhelming fast… For those truly being abused, we’re here to help. The tricky bit is that most I speak with aren’t being bullied unfairly. They are infringing and are properly being taken down. An important distinction.”

(Follow up question from a Reddit reader)

“[Q:] Are they contacting you knowing that they are in the wrong or just oblivious?

[A:] Mostly the second. A good portion of the Internet feels no one owns anything and everything is fair use. It’s not.” 64

And, of course, fair use is not a simple analysis, and every case is different. I direct you to this recent decision in the closely watched Georgia State fair use case. 65 Here, it takes the Judge 213 pages to analyze 48 cases of fair use. And this is where this first factor was deemed to favor Georgia State in all the cases.

Fair use is not simple, is not easy and requires rigorous analysis. Fair use requires more than ipse dixit. So, the study’s claim that there could be as many 8 million cases of takedowns aimed at “potential fair use” 66 just does not hold up, given their over-expansive position on what constitutes actual fair use.

How Can You Reach Conclusions Without Actually Talking to People?

As noted above, the study reached broad conclusions about the counter-notice and why it was under-used. The study contends counter-notice provisions are “ineffective, empowering unscrupulous users and subjecting legitimate ones to legal jeopardy. Targets were widely considered to lack sufficient information to respond to mistaken or abusive notices.” 67

The study came to this conclusion without actually talking to a single person who was the “target” of a takedown notice. 68 How did they come to this conclusion? Well, they talked to the online service providers about their interactions with the “targets.” 69 This is what lawyers call “hearsay,” and it’s generally inadmissible in Court.

Perhaps, one reason that the counter-notice is underused is because it is far easier to re-post the material than to file the counter-notice. This, of course, is the whack-a-mole problem that the study consistently ignores.

The other possibility as noted above by Jonathan Bailey of Plagiarism Today is that what many of the posters claim is fair use is in fact infringing content.

Additionally, the study notes that “OSPs noted that in their experience, these ‘small senders’ are most likely to misunderstand the notice and takedown process, mistake the statutory requirements, or use it for clearly improper purposes.” 70 In other words, the small senders create most of the problems and it is these people that Google needs enhanced protection from.

So, did the study actually talk to any “small senders” to determine why errors were made, and how they might be corrected?

Nope. 71

How Come Your Data Is So Different From Google’s?

Google’s own transparency report states that as recently as 2011, Google processed 97.3% of all takedowns as correct. This report claims that bad notices constitute nearly 30%. What’s the explanation for this rather large discrepancy? The study posits that Google must have taken down many notices that were not compliant anyway, with no corresponding data to back it up.

Are There Other Factors Which Cause Bad Notices?

The study could have taken a look at just how Google makes it extremely difficult to find out what the “correct” URL for an infringing file is. Here’s Ellen Siedler’s account of her personal experience from the Vox Indie website, published more than a month before the subject study was posted.

“Let’s say eventually (once you create a Google account and login) you end up at the right DMCA form, guess what? You’re still not finished. You’ll need to have the correct URL to report. That seems simple enough…you already copied the URL from the address bar of the pirated stream so that’s the link to report, right? WRONG! That would be too easy.

If you did report that URL nothing will happen. You must READ THE FINE PRINT on the DMCA form silly. Apparently the URL that appears in the address bar that appears–when you click a film to watch it in a new window– is NOT really the link to the pirated movie. It’s actually the URL for the Drive folder and, as the fine print notes, this type of URL is ‘unacceptable.’

So how to you find the right URL to report? Google doesn’t offer up any tips on that front. To find an actual link specific to the pirated movie requires some further detective work. Return to the page with the pirated stream and poke around. There’s nothing that says “here’s the video link” but after clicking various clickable things you may, if you’re lucky, eventually discover that by navigating to menu bar and sliding your cursor over the three dots–an option for more actions appears.

From there if you click report abuse you’ll arrive at yet another page with a new URL. You’re asked to click the type of abuse….Warning, if you select report “copyright abuse” then ruh roh, you end up back at the beginning the DMCA maze that Google has so conveniently created to impede and confuse you once again.

It’s an absurd maze, but for Google, it’s clearly no accident.” 72

The fact that Google deliberately obfuscates what constitutes an acceptable URL, and how this might factor into the rate of incorrect notices, is never addressed by the study.

Note also that under the law Google is required to have a DMCA agent whose job it is to receive takedown requests. If you do a search for “Google DMCA agent,” Google will send you to this page 73 which not only does not provide the name and address of who the DMCA agent is, but never mentions the words “DMCA agent” at all. For that, you have to go to the Copyright Office website. 74 It provides this URL: http://www.google.com/dmca.html as the place to “Submit Notices of Claimed Infringement.” This link will take you to this page 75 which states “to file a notice of infringement with us, please file a complaint using the steps available at our legal troubleshooter.” Clicking on that link takes you back to the same page noted at endnote 73, which of course makes no mention of the DMCA at all and puts you at about step 14 out of the 46+ steps as noted in last week’s blog post. 76

Do You Understand the English Language?

So back to the study. Recall that in the study of notices sent to Google Images that one person had sent 52.9% of all of the incorrect notices. 77 So, let’s take her out of the equation. Of the remaining notices, 56.5% of those notices were sent by people outside the United States, including Germany, China, and Israel. 78 Gosh, do you think that given that almost 80% of these notices are being sent by people for whom a) English is not their primary language and b) are trying to interpret some fairly complex requirements of U.S. Copyright law, might have something to do with the rate of incorrect notices? This possibility is never addressed.

It’s Not a Violation of Due Process If You Don’t Defend

Here’s another head scratcher. The study concludes that since so few people use the counter-notice provisions, that this amounts to a denial of due process.

“The quantitative studies, which showed no use of the counter notice process, reinforced this concern. Without better accuracy requirements for notices, a reasonable ability to respond before action is taken, and an unbiased adjudicator to decide whether takedown is appropriate, counter notice and putback procedures fail to offer real due process protection to targets.” 79

If you are sued in a lawsuit and don’t respond or defend the suit, a default judgement will be entered against you. That’s the way the system works. Due process exists to give you an opportunity to respond to the charges (civil or criminal). If you don’t contest them, you lose the case.

If you get a takedown notice and don’t respond with a counter-notice, then your stuff will be taken down and it will stay down. That’s because you did not respond once given notice and opportunity to respond. This is not a denial of due process.

The “unbiased adjudicator” called for by the study is called a judge. That’s what you get when you file a counter-notice and the copyright owner takes you to Court. There is absolutely no need to inject another “unbiased adjudicator” into the process.

Recommends Changes to the Copyright Law That Only Burdens Persons Sending Notices

Amongst the recommended changes to the law, the study only recommends those that place increased burdens on those senders of notice, but not those receiving them. They include: 80

- Require takedown notice to be under penalties of perjury and create statutory damages for incorrect notices.

- Require immediate putback for files for which a counter-notice is served.

- Remove the “per work infringed” metric from statutory damages.

Why no requirement of take down stay down? Because that would be too “burdensome.” 81 Never mind that these are the businesses that are directly profiting from the posting of infringing material. Instead, they would rather create quasi-criminal penalties for making a simple mistake, or in the case of fair use, an area in which there can be (and is) room for substantial disagreement.

Consider the call for “immediate putback” of work for which a counter notice is filed. The study claims that:

“The ten-day waiting period is routinely criticized for jeopardizing expression, especially time-sensitive expression. Given the very small number of counter notices received by OSPs and the high social cost of censoring expression, any costs related to this change would be far outweighed by the benefit of fixing this problem.” 82

Except for the fact that piracy is also time sensitive and occurs with the greatest frequency when a new work is released. Consider this report from 2014:

“The latest episode of Game of Thrones has broken the record for the most people sharing a file simultaneously via BitTorrent. More than 193,000 people shared a single copy yesterday evening, and roughly 1.5 million people downloaded the episode during the first day.” 83

So a bogus counter-notice gets your infringing content put back up, during the short period of time when it is most valuable, and acts of piracy are the greatest. Clearly, the authors have not thought that one through.

And what’s the remedy for a bogus counter-notice, such as one that claims that they are in fact the owner of the material, or a phony assertion of “mistake or misidentification,” or a totally fictitious name and address? What’s the remedy for that?

There currently is no remedy. Why don’t the authors suggest one?

It does not appear the authors have considered that question. Because at the end of the day, it’s not Google’s problem, is it?

Notes:

- Jennifer M. Urban, Joe Karaganis, and Brianna L. Schofield, Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice ↩

- Study Finds Major Flaws in DMCA Takedown Procedure and Policing the Pirates: 30% of Takedown Requests Are Questionable (Study) ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 79 (emphasis added) ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at “Acknowledgement and Disclosures” ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 40 ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 128-129 ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at “Acknowledgement and Disclosures” ↩

- The Takedown Project ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 128 ↩

- U.S. Public Policy – Transparency ↩

- Lumen – About Us ↩

- The EFF and Google: Too Close for Comfort? ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 128-129 ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 60 ↩

- Google Transparency Report FAQ ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 95 ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 96 ↩

- 28% of Piracy Takedown Requests Are “Questionable” ↩

- Blame the Robots for Copyright Notice Dysfunction ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 81 ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 98 ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 102 ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 100 ↩

- “Most pointed to written material she alleges is defamatory, harassing, slanderous or threatening.” Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 100. The study contends most likely 100% of her notices are defective. Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 107. ↩

- Why Does Google Make It So Damn Difficult to Send a DMCA Notice? ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 95 ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 110 ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 141 ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 27 ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 74 ↩

- Grooveshark Is Now Deadshark: How an Illegal Streaming Service Hid Behind the DMCA for Nearly 10 Years ↩

- 14 Strikes and You’re Out! (Maybe): How Cox Communications Lost its DMCA Safe Harbor ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 66-67 ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 91-92 ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 33 footnote 93 ↩

- Study Finds Major Flaws in DMCA Takedown Procedure, Columbia University Researchers Claim 28% of Google’s URL Takedown Requests Are Invalid, How We’re Unwittingly Letting Robots Censor the Web, Blame the Robots for Copyright Notice Dysfunction, 28% of Piracy Takedown Requests Are “Questionable”, Policing the Pirates: 30% of Takedown Requests Are Questionable (Study) ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at “Acknowledgement and Disclosures” ↩

- The Takedown Project ↩

- Lumen – About Us ↩

- The EFF and Google: Too Close for Comfort?[/ref] Not to mention, former EFF Senior Staff Counsel Fred Von Lohmann is now Google Senior Copyright Counsel Fred Von Lohmann, who also was a visiting researcher with the Berkeley Center for Law and Technology. 84Fred von Lohmann ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 128 ↩

- Google U.S. Public Policy – Transparency ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at “Acknowledgement and Disclosures” ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 51, footnote 155 ↩

- Anti-Piracy Activist Issues Takedown To Chilling Effects To Take Down Her Takedown Notice To Google ↩

- Columbia University Researchers Claim 28% of Google’s URL Takedown Requests Are Invalid ↩

- Blame the Robots for Copyright Notice Dysfunction ↩

- 28% of Piracy Takedown Requests Are “Questionable” ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 81 ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 1 ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 88 footnote 246 ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 100 ↩

- Id. ↩

- Copyright Office Section 512 Study – EFF 512 Study Comments ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 3 ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 61 ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 95 ↩

- Id. ↩

- Marching Bravely Into the Quagmire: The Complete Mess that the “Transformative” Test Has Made of Fair Use, and Copyright Blog Update: Court of Appeals Rejects “Transformative Use” Test & Malibu Media Marches Along ↩

- Dr. Seuss Enterprises v. Penguin Books USA, Inc. 109 F3rd 1394 Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals 1997 ↩

- Kienetz v. Sconnie Nation, LLC, 2014 WL 4494835, Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals 2104 ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 27 ↩

- My Comments to the Copyright Office on DMCA Safe Harbor ↩

- VideoGameAttorney here to answer questions about fair use, copyright, or whatever the heck else you want to know! ↩

- Georgia State Fair Use Case ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 97 ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 74 ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 27 ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 27 ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 40 ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 141 ↩

- Why Does Google Make It So Damn Difficult to Send a DMCA Notice? ↩

- Google Legal Help – Legal Removal Requests ↩

- Google Amended Interim Designation of Agent to Receive Notification of Claimed Infringement ↩

- Google Legal Help – Digital Millennium Copyright Act ↩

- How to Send a Takedown Notice to Google in 46 (or more) Easy Steps! ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 100 ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 102 ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 3 ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 128-129 ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 123 and 140 ↩

- Notice and Takedown in Everyday Practice, at 128 ↩

- Game of Thrones Sets New Torrent Swarm Record ↩