On June 16, 2016, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals released a truly horrific opinion in the case of Capitol Records v. Vimeo.[ref]2016 WL 3349368 Second Circuit Court of Appeals[/ref]

The case involved the Plaintiffs, all record companies with ownership of pre-1972 sound recordings, which are not governed by Federal law but have been ruled as having performance rights in California and New York.[ref]Flo and Eddie v. Sirius XM Radio: Have Two Hippies from the 60's Just Changed the Course of Broadcast Music?[/ref] Vimeo, as Jonathan Bailey over at Plagiarism Today quipped is best known as "not You Tube,"[ref]Understanding Capitol Records v. Vimeo[/ref] makes performances of these sound recordings by allowing users to upload videos containing these sound recordings. Not only does Vimeo make performances of these sound recordings, but distributes copies of them by allowing viewers to download the videos and copy them for free.[ref]Vimeo at page 5[/ref]

If I might steal a page from the Electronic Frontier Foundation, the decision is "dangerous" in every sense of the word. It threatens to undo the clear intention of Congress by making the most basic error that a Court can make: ignoring the "plain meaning" of a statute.

In sum, the Court:

- Ruled that even though "Pre-1972 recordings have never been covered by the federal copyright"[ref]Vimeo at 6[/ref] they nevertheless are covered by federal copyright for the purposes of notice and takedown.

- Ruled the "safe harbor" provisions of section 512 apply to pre-1972 sound recordings, even though section 301 clearly says they cannot.

- Ignored the contrary opinion of the Copyright Office that said safe harbor did not apply to pre-1972 sound recordings.

- Called the notice and takedown system "an augmentation of rights of copyright owners,[ref]Id. at 3[/ref] but when challenged on this position by an amicus curae that the system "shortchanged" copyright owners, contradicts itself and says "we have no way of knowing."[ref]Id. at 15 endnote 4[/ref]

- Says workers at Vimeo can't be held responsible for knowing when something is infringing because they are not "an expert in music or the law of copyright." [ref]Id. at 10[/ref]

- Examples of Vimeo employees encouraging users to upload infringing content "cannot support a finding of…generalized encouragement of infringement."[ref]Id. at 13[/ref]

So what do the Courts say on this subject? Mostly, they say that simply taking a work and making it dirty, does not make it a parody or fair use.

The oldest and most widely cited case is Walt Disney Productions v. Air Pirates,[ref]581 F.2d 751 9th Circuit Court of Appeals (1978)[/ref] which dates from 1978.

"The individual defendants have participated in preparing and publishing two magazines of cartoons entitled "Air Pirates Funnies." The characters in defendants' magazines bear a marked similarity to those of plaintiff. The names given to defendants' characters are the same names used in plaintiff's copyrighted work… the "Air Pirates" was "an ‘underground' comic book which…centered around "a rather bawdy depiction of the Disney characters as active members of a free thinking, promiscuous, drug ingesting counterculture."[ref]Id. at 753[/ref]

"Defendants do not contend that their admitted copying was not substantial enough to constitute an infringement, and it is plain that copying a comic book character's graphic image constitutes copying to an extent sufficient to justify a finding of infringement. (citations omitted) Defendants instead claim that this infringement should be excused through the application of the fair use defense, since it purportedly is a parody of Disney's cartoons."[ref]Id. at 756[/ref]

The 9th Circuit wasn't buying it. It upheld the District Court's grant of summary judgment finding copyright infringement stating:

"[W]hen persons are parodying a copyrighted work, the constraints of the existing precedent do not permit them to take as much of a component part as they need to make the "best parody." Instead, their desire to make the "best parody" is balanced against the rights of the copyright owner in his original expressions. That balance has been struck at giving the parodist what is necessary to conjure up the original, and in the absence of a special need for accuracy (citation omitted) that standard was exceeded here. By copying the images in their entirety, defendants took more than was necessary to place firmly in the reader's mind the parodied work and those specific attributes that are to be satirized."[ref]Id. at 758[/ref]

From then on, any claim of "parody" where the resulting parody was sexually explicit, fared very poorly in the Court system.

An off-Broadway show that rewrote the lyrics to "Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy of Company B" to become the "Cunnilingus Champion of Company C" was held not to be a parody and not fair use.[ref]MCA, Inc. v.Wilson 677 F.2d 180 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals 1981[/ref]

"We are not prepared to hold that a commercial composer can plagiarize a competitor's copyrighted song, substitute dirty lyrics of his own, perform it for commercial gain, and then escape liability by calling the end result a parody or satire on the mores of society. Such a holding would be an open-ended invitation to musical plagiarism. We conclude that defendants did not make fair use of plaintiff's song."[ref]Id.at 186[/ref]

Even further, the mere use of the costume of the Dallas Cowboy Cheerleaders in a porn film was deemed not to be a fair use and was sufficient to sustain a preliminary injunction against the showing of the film.[ref]Dallas Cowboy Cheerleaders, Inc. v. Pussycat Cinema, 604 F.2d 200 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals 1979[/ref]

"The public's belief that the mark's owner sponsored or otherwise approved the use of the trademark satisfies the confusion requirement. In the instant case, the uniform depicted in "Debbie Does Dallas" unquestionably brings to mind the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders. Indeed, it is hard to believe that anyone who had seen defendants' sexually depraved film could ever thereafter disassociate it from plaintiff's cheerleaders. This association results in confusion which has "a tendency to impugn (plaintiff's services) and injure plaintiff's business reputation…[ref]Id. at 205[/ref] Although, as defendants assert, the doctrine of fair use permits limited copyright infringement for purposes of parody, (citations omitted) defendants' use of plaintiff's uniform hardly qualifies as parody or any other form of fair use."[ref]Id. at 206[/ref]

But then, there was a split decision out of Georgia where Pillsbury, being offend by a "parody ad" in Screw Magazine depicting "Poppin' Fresh" and "Poppy Fresh" engaged in sexual relations, sued for both copyright and trademark infringement.[ref]Pillsbury Co. v. Milky Way Productions U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Georgia, 1981 WL 1402[/ref] There, the Court found that the use was indeed a "fair use" because Pillsbury's "failure to show any appreciable harm to the potential market for or the value of its copyrighted works bears significantly upon the relative fairness of Milky Way's unauthorized use of these copyrighted works. There is no showing that Milky Way intended to fill the demand for the original or that its presentation had this effect."[ref]Id.[/ref]

The Court did, however, find that the use had "diluted" the effectiveness of Pillsbury's trademarks in the characters and that Pillsbury "has sustained its burden on its claim that the defendants infringed its copyright on the cinnamon roll label, [and] that the plaintiff has sustained its burden on its claim that the defendants infringed its copyright on its jingle, the two stanza refrain of ‘The Pillsbury Baking Song.'"[ref]Id.[/ref]

Flash forward 20 years. George Lucas, unhappy about a porn parody of "Star Wars" titled "StarBallz," sought a preliminary injunction against its further distribution, and was turned down flat.[ref]LucasFilm Ltd. V. Media Market Group, 182 F.Supp2d 897 U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, 2002[/ref] Without any analysis of the four fair use factors at all, the Court blithely concludes that "[a] preliminary analysis of the fair use factors indicates that LucasFilm is not likely to succeed in its copyright claim because the parodic nature of Starballz may constitute fair use."[ref]Id. at 901[/ref]

Remember that this Court is under the jurisdiction of the 9th Circuit, where the Air Pirates case is good law.

This decision invokes the very question: what does a "porn parody" say about the work it is copied from? What aspect of the original work is being criticized, commented on, or being made fun of?

What does the portrayal of Disney Princesses having sex with their "handsome princes" (presumably the "happily ever after" part of the relationship) say about them? Anything at all? Where, in fact, is the "parody" that is being asserted?

But what of the Judge's reasoning that such uses do not do "appreciable harm to the potential market for or the value of its copyrighted works"?[ref]Pillsbury Co. v. Milky Way Productions U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Georgia, 1981 WL 1402[/ref]

Well, in 1981, the Judge could not foresee the effect of the internet, where certain uses become so popular that they overwhelm the primary use. According to this article in PCGamesN.com:

"The internet has gone Overwatch mad. At one point on Monday, the game's subreddit actually had more readers than Reddit's own front page - it's that popular. Of course, with this level of popularity, there's also porn - loads and loads of porn, to the point where there's even a subreddit entirely dedicated to Overwartch sexytimes…During Overwatch's beta, there was a rise (yes) of around 800% in searches for Overwatch porn, according to a release from [website omitted], with Tracer bagging the dubious honour of being the most searched character."[ref]

So what do the Courts say on this subject? Mostly, they say that simply taking a work and making it dirty, does not make it a parody or fair use.

The oldest and most widely cited case is Walt Disney Productions v. Air Pirates,[ref]581 F.2d 751 9th Circuit Court of Appeals (1978)[/ref] which dates from 1978.

"The individual defendants have participated in preparing and publishing two magazines of cartoons entitled "Air Pirates Funnies." The characters in defendants' magazines bear a marked similarity to those of plaintiff. The names given to defendants' characters are the same names used in plaintiff's copyrighted work… the "Air Pirates" was "an ‘underground' comic book which…centered around "a rather bawdy depiction of the Disney characters as active members of a free thinking, promiscuous, drug ingesting counterculture."[ref]Id. at 753[/ref]

"Defendants do not contend that their admitted copying was not substantial enough to constitute an infringement, and it is plain that copying a comic book character's graphic image constitutes copying to an extent sufficient to justify a finding of infringement. (citations omitted) Defendants instead claim that this infringement should be excused through the application of the fair use defense, since it purportedly is a parody of Disney's cartoons."[ref]Id. at 756[/ref]

The 9th Circuit wasn't buying it. It upheld the District Court's grant of summary judgment finding copyright infringement stating:

"[W]hen persons are parodying a copyrighted work, the constraints of the existing precedent do not permit them to take as much of a component part as they need to make the "best parody." Instead, their desire to make the "best parody" is balanced against the rights of the copyright owner in his original expressions. That balance has been struck at giving the parodist what is necessary to conjure up the original, and in the absence of a special need for accuracy (citation omitted) that standard was exceeded here. By copying the images in their entirety, defendants took more than was necessary to place firmly in the reader's mind the parodied work and those specific attributes that are to be satirized."[ref]Id. at 758[/ref]

From then on, any claim of "parody" where the resulting parody was sexually explicit, fared very poorly in the Court system.

An off-Broadway show that rewrote the lyrics to "Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy of Company B" to become the "Cunnilingus Champion of Company C" was held not to be a parody and not fair use.[ref]MCA, Inc. v.Wilson 677 F.2d 180 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals 1981[/ref]

"We are not prepared to hold that a commercial composer can plagiarize a competitor's copyrighted song, substitute dirty lyrics of his own, perform it for commercial gain, and then escape liability by calling the end result a parody or satire on the mores of society. Such a holding would be an open-ended invitation to musical plagiarism. We conclude that defendants did not make fair use of plaintiff's song."[ref]Id.at 186[/ref]

Even further, the mere use of the costume of the Dallas Cowboy Cheerleaders in a porn film was deemed not to be a fair use and was sufficient to sustain a preliminary injunction against the showing of the film.[ref]Dallas Cowboy Cheerleaders, Inc. v. Pussycat Cinema, 604 F.2d 200 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals 1979[/ref]

"The public's belief that the mark's owner sponsored or otherwise approved the use of the trademark satisfies the confusion requirement. In the instant case, the uniform depicted in "Debbie Does Dallas" unquestionably brings to mind the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders. Indeed, it is hard to believe that anyone who had seen defendants' sexually depraved film could ever thereafter disassociate it from plaintiff's cheerleaders. This association results in confusion which has "a tendency to impugn (plaintiff's services) and injure plaintiff's business reputation…[ref]Id. at 205[/ref] Although, as defendants assert, the doctrine of fair use permits limited copyright infringement for purposes of parody, (citations omitted) defendants' use of plaintiff's uniform hardly qualifies as parody or any other form of fair use."[ref]Id. at 206[/ref]

But then, there was a split decision out of Georgia where Pillsbury, being offend by a "parody ad" in Screw Magazine depicting "Poppin' Fresh" and "Poppy Fresh" engaged in sexual relations, sued for both copyright and trademark infringement.[ref]Pillsbury Co. v. Milky Way Productions U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Georgia, 1981 WL 1402[/ref] There, the Court found that the use was indeed a "fair use" because Pillsbury's "failure to show any appreciable harm to the potential market for or the value of its copyrighted works bears significantly upon the relative fairness of Milky Way's unauthorized use of these copyrighted works. There is no showing that Milky Way intended to fill the demand for the original or that its presentation had this effect."[ref]Id.[/ref]

The Court did, however, find that the use had "diluted" the effectiveness of Pillsbury's trademarks in the characters and that Pillsbury "has sustained its burden on its claim that the defendants infringed its copyright on the cinnamon roll label, [and] that the plaintiff has sustained its burden on its claim that the defendants infringed its copyright on its jingle, the two stanza refrain of ‘The Pillsbury Baking Song.'"[ref]Id.[/ref]

Flash forward 20 years. George Lucas, unhappy about a porn parody of "Star Wars" titled "StarBallz," sought a preliminary injunction against its further distribution, and was turned down flat.[ref]LucasFilm Ltd. V. Media Market Group, 182 F.Supp2d 897 U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, 2002[/ref] Without any analysis of the four fair use factors at all, the Court blithely concludes that "[a] preliminary analysis of the fair use factors indicates that LucasFilm is not likely to succeed in its copyright claim because the parodic nature of Starballz may constitute fair use."[ref]Id. at 901[/ref]

Remember that this Court is under the jurisdiction of the 9th Circuit, where the Air Pirates case is good law.

This decision invokes the very question: what does a "porn parody" say about the work it is copied from? What aspect of the original work is being criticized, commented on, or being made fun of?

What does the portrayal of Disney Princesses having sex with their "handsome princes" (presumably the "happily ever after" part of the relationship) say about them? Anything at all? Where, in fact, is the "parody" that is being asserted?

But what of the Judge's reasoning that such uses do not do "appreciable harm to the potential market for or the value of its copyrighted works"?[ref]Pillsbury Co. v. Milky Way Productions U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Georgia, 1981 WL 1402[/ref]

Well, in 1981, the Judge could not foresee the effect of the internet, where certain uses become so popular that they overwhelm the primary use. According to this article in PCGamesN.com:

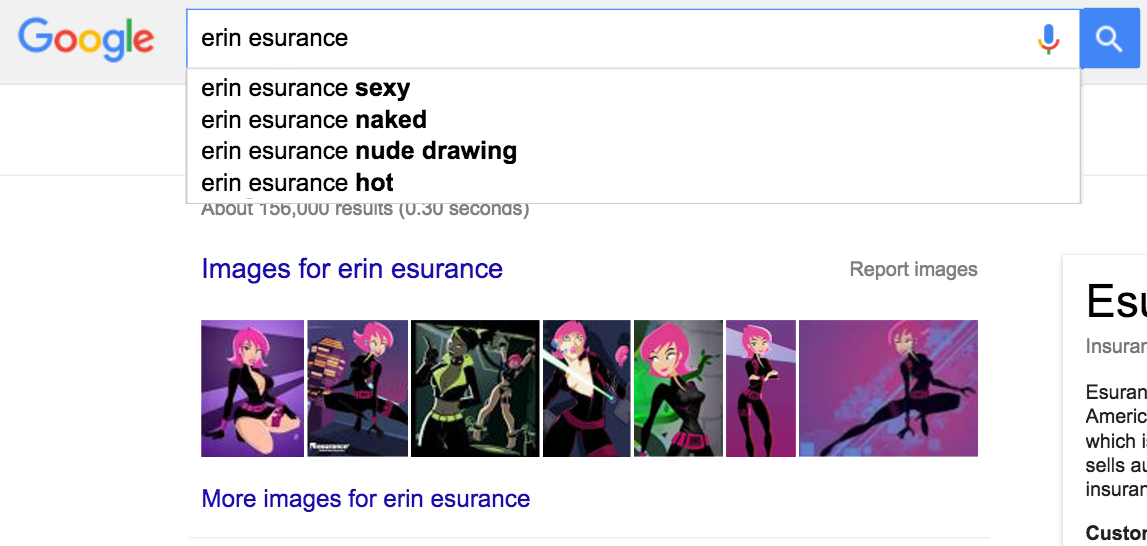

"The internet has gone Overwatch mad. At one point on Monday, the game's subreddit actually had more readers than Reddit's own front page - it's that popular. Of course, with this level of popularity, there's also porn - loads and loads of porn, to the point where there's even a subreddit entirely dedicated to Overwartch sexytimes…During Overwatch's beta, there was a rise (yes) of around 800% in searches for Overwatch porn, according to a release from [website omitted], with Tracer bagging the dubious honour of being the most searched character."[ref] "Over the next five years, the market for lewd artistic renditions of Erin grew in tandem with her commercial ubiquity. [Website omitted] and other online art hubs became something of a stomping grounds for peddlers of cartoon porn, and many artists made a healthy supplemental income by selling Erin Esurance drawings through various platforms."[ref]Id.[/ref]

"The commercial inspired this particular gentleman to create a series of 15 "extremely NSFW" Erin Esurance paintings, which he later sold for up to $120 through [website omitted], a "giant, searchable archive" of cartoon porn."[ref]Id.[/ref]

So, in addition to being on shaky grounds as a "parody," the purpose and character of the use seems more and more to be one of commercial gain by the artists themselves. Clearly, the websites know they are on the wrong side of the law on this one. Consider this actual TOS from one website:

"You will not hold the webmasters and staff of this website liable for any damages incurred by viewing the content contained herein. No harm is or ever will be intended against the financial earnings of the copyright owners of the characters and related properties depicted within.

This site is not affiliated with the copyright owners of any characters or related properties depicted in anyway on this site.

Anyone who enters this website that is affiliated with any characters / series depicted on the images within this site must do so in their own private time and not use the content of this site to issue lawsuits against the owners or staff of [website omitted] or our webhost."

I like to see that one tested in Court.

Even further, in the sites FAQ's with regards to reasons for having images taken down, one of the reasons is not "copyright infringement" but the fact that a submitted illustration does not contain porn, for which there is an additional handy definition of what does and does not constitute porn.

So why doesn't Disney do something? Beats me. Especially for a company known to be very litigious and very protective of their characters.

Disney can't possibly not know that this is happening all over the internet. In fact, one website has both the words "Disney" and "porn" in its domain name. Many sites are posting the illustrations themselves, which takes them out of DMCA safe harbor. And some of the stuff is pretty nasty. Bestiality anyone?

Surely Disney is not losing money here, as it has no real intention of entering the pornography market. But the artists behind the so-called "porn parody" market are making money, in some cases what appears to be a significant amount, all based on a value they did not create. People are going to these websites because of what Disney did first, not what they did after it became popular.

So, it boils down to the age-old schoolboy tactic of entertaining yourself by making a child's plaything do something salacious and out of character. But as the majority of the cases show, simply calling something a parody does not make it so, just as calling wholesale copying of another's work "fair use" is not a magic trump card that makes it legal.

"Over the next five years, the market for lewd artistic renditions of Erin grew in tandem with her commercial ubiquity. [Website omitted] and other online art hubs became something of a stomping grounds for peddlers of cartoon porn, and many artists made a healthy supplemental income by selling Erin Esurance drawings through various platforms."[ref]Id.[/ref]

"The commercial inspired this particular gentleman to create a series of 15 "extremely NSFW" Erin Esurance paintings, which he later sold for up to $120 through [website omitted], a "giant, searchable archive" of cartoon porn."[ref]Id.[/ref]

So, in addition to being on shaky grounds as a "parody," the purpose and character of the use seems more and more to be one of commercial gain by the artists themselves. Clearly, the websites know they are on the wrong side of the law on this one. Consider this actual TOS from one website:

"You will not hold the webmasters and staff of this website liable for any damages incurred by viewing the content contained herein. No harm is or ever will be intended against the financial earnings of the copyright owners of the characters and related properties depicted within.

This site is not affiliated with the copyright owners of any characters or related properties depicted in anyway on this site.

Anyone who enters this website that is affiliated with any characters / series depicted on the images within this site must do so in their own private time and not use the content of this site to issue lawsuits against the owners or staff of [website omitted] or our webhost."

I like to see that one tested in Court.

Even further, in the sites FAQ's with regards to reasons for having images taken down, one of the reasons is not "copyright infringement" but the fact that a submitted illustration does not contain porn, for which there is an additional handy definition of what does and does not constitute porn.

So why doesn't Disney do something? Beats me. Especially for a company known to be very litigious and very protective of their characters.

Disney can't possibly not know that this is happening all over the internet. In fact, one website has both the words "Disney" and "porn" in its domain name. Many sites are posting the illustrations themselves, which takes them out of DMCA safe harbor. And some of the stuff is pretty nasty. Bestiality anyone?

Surely Disney is not losing money here, as it has no real intention of entering the pornography market. But the artists behind the so-called "porn parody" market are making money, in some cases what appears to be a significant amount, all based on a value they did not create. People are going to these websites because of what Disney did first, not what they did after it became popular.

So, it boils down to the age-old schoolboy tactic of entertaining yourself by making a child's plaything do something salacious and out of character. But as the majority of the cases show, simply calling something a parody does not make it so, just as calling wholesale copying of another's work "fair use" is not a magic trump card that makes it legal.