"We have not, to date, accepted that freedom of expression requires the facilitation of the unlawful sale of goods."[ref]Google v. Equustek Solutions Inc[/ref]

With those incisive words, the Supreme Court of Canada finally called Google out for its long time practice of turning a blind eye to infringement of intellectual property, and ordered that Google block a pirate site, not just in Canada, but around the world. The case is landmark decision in the protection of intellectual property, and one that is going to instruct creators and artists on how to best protect their creations. The case in question is Google v. Equustek Solutions Inc. This blog has written about this case previously.[ref]Courts in Canada, Germany and U.S. Order Website Blocking, Internet Fails to Spontaneously Self-Destruct[/ref] "In [this] action, the Plaintiff found that the Defendant, a former distributor of Plaintiff's, was making counterfeit copies of its industrial network interface hardware. During the course of the litigation, the Defendants stopped responding to the Court's Orders, closed up their Canadian location, and continued to sell the counterfeit goods through a variety of internet portals in a twist on the old "whack-a-mole" strategy in which faithful readers of this blog will be familiar. The Plaintiffs applied for, and were granted, an order against Google requiring it to remove the Defendant's websites from their search results on a worldwide basis."[ref]Id.[/ref] Also, as noted before on this blog, Google routinely blocks websites for all sorts of reasons.[ref]Google Blacklists 10,000 Sites a Day; Why Doesn't It Blacklist Pirate Sites?[/ref] In fact, they blacklisted all of a Florida company's websites from Google search results, a total of 231 websites in all.[ref]Suit Alleging Google's Claim That It Does Not Censor Search Results Is "False, Deceptive and Misleading" Moves Forward[/ref] So, it's not the case that Google can't do what the Court has ordered, it's just that it doesn't want to. "The order does not require that Google take any steps around the world, it requires it to take steps only where its search engine is controlled. This is something Google has acknowledged it can do — and does — with relative ease. There is therefore no harm to Google which can be placed on its "inconvenience" scale arising from the global reach of the order."[ref]Google v. Equustek Solutions Inc at 23[/ref] And, let's not forget that Google is not some unaware third party dragged in off the street. As the previous decision by the Court of Appeals noted: "In addition to its search services, Google sells advertising to British Columbia clients. Indeed, Google entered into an advertising contract with the defendants and advertised their products up to the hearing of this application. Google acknowledges it should not advertise for the defendants and filed an affidavit explaining its inadvertent failure to suspend the defendants' Google account prior to the hearing."[ref]Equustek Solutions Inc. v. Google Inc. at paragraph 50[/ref] (emphasis added) This is the most pungent example of why Google doesn't block rogue websites: they make too much money selling them advertising and keywords. The problem is that Google's business is global. And the internet is global. An injunction that ran only to Canada would be a toothless tiger. "The problem in this case is occurring online and globally. The Internet has no borders — its natural habitat is global. The only way to ensure that the interlocutory injunction attained its objective was to have it apply where Google operates — globally. As [the lower court] found, the majority of Datalink's sales take place outside Canada. If the injunction were restricted to Canada alone or to google.ca, as Google suggests it should have been, the remedy would be deprived of its intended ability to prevent irreparable harm. Purchasers outside Canada could easily continue purchasing from Datalink's websites, and Canadian purchasers could easily find Datalink's websites even if those websites were de-indexed on google.ca. Google would still be facilitating Datalink's breach of the court's order which had prohibited it from carrying on business on the Internet. There is no equity in ordering an interlocutory injunction which has no realistic prospect of preventing irreparable harm."[ref]Google v. Equustek Solutions Inc at 23[/ref] (emphasis added) Then there's this silly argument by Google: That somehow by obeying the order it might, in some way, theoretically, be violating the law of some foreign territory.[ref]Id. at 24[/ref] Really? Yes, some countries have lax enforcement of their intellectual property laws. But name me one country where the protection of intellectual property is actually prohibited by law. The Supreme Court wasn't buying this either: "If Google has evidence that complying with such an injunction would require it to violate the laws of another jurisdiction, including interfering with freedom of expression, it is always free to apply to the British Columbia courts to vary the interlocutory order accordingly. To date, Google has made no such application." The Supreme Court then lays out what is plain to everyone that has ever been ripped off on the internet: "Datalink and its representatives have ignored all previous court orders made against them, have left British Columbia, and continue to operate their business from unknown locations outside Canada…Datalink is only able to survive — at the expense of Equustek's survival — on Google's search engine which directs potential customers to its websites. In other words, Google is how Datalink has been able to continue harming Equustek in defiance of several court orders…This does not make Google liable for this harm. It does, however, make Google the determinative player in allowing the harm to occur."[ref]Id. at 26[/ref] The Electronic Frontier Foundation, which had filed "friend of the Court" briefs (shouldn't that be a "friend of Google" brief?) predictably howled with outrage and predicted the demise of the internet as we know it. "Top Canadian Court Permits Worldwide Internet Censorship"[ref]Top Canadian Court Permits Worldwide Internet Censorship[/ref] screams the headline. Besides falsely claiming that Google was an "innocent third party" (remember they sold the defendants advertising in violation of the lower court order) the EFF claims that "[b]eyond the flaws of the ruling itself, the court's decision will likely embolden other countries to try to enforce their own speech-restricting laws on the Internet, to the detriment of all users." First of all, nothing prevents a country, any country, from doing what it wants, and applying its own laws, in any way they see fit. Even if we don't like it. If Google doesn't like the laws of a certain country, say China or Iran (the boogey men trotted out by the EFF), then Google can stop doing business in those countries. Seriously, China is going to base what it does regarding free speech due to a decision by a Court in Canada? Plus, this is just another indication of the EFF's inability to distinguish free speech and intellectual property infringement. They are not the same thing. Going back to the quote that led off this post: "This is not an order to remove speech that, on its face, engages freedom of expression values, it is an order to de-index websites that are in violation of several court orders. We have not, to date, accepted that freedom of expression requires the facilitation of the unlawful sale of goods."[ref]Google v. Equustek Solutions Inc at 25[/ref]

Cloudflare, the most notorious purveyor of internet peek-a-boo,[ref]Cloudflare: The "Now You See Me, Now You Don't" of the Internet[/ref] found itself back in Court again, this time on the receiving end of a lawsuit brought by porn website ALS Scan.[ref]ALS Scan v. Cloudflare, Inc. et al CV 16-5051-GW (AFMx) Central District of CA, 2017 the document can be accessed at: https://torrentfreak.com/images/cloudpartial.pdf[/ref] The allegations of the complaint are that by providing CDN services to 13 pirate websites, Cloudflare is guilty of contributory infringement of the copyrighted photographs of the Plaintiff.

The Plaintiff's allegations are summed up by the Court as follows:

"According to Plaintiff, [Cloudflare's] service allows consumers seeking to access a Cloudflare client's website to retrieve the website's content from the closest Cloudflare data center, rather than accessing the content from the primary host. This purportedly results in a client's website content loading twice as fast for website users, regardless of where the users are located.

In addition, the [Third Amended Compliant] alleges that Cloudflare's DNS services "allow pirate sites and their hosts to conceal their identity from copyright owners. The domain registration information for some of the pirate sites . . . indicate that the sites reside on a Cloudflare server in Phoenix, Arizona. When presented with a notice of infringement, however, Cloudflare . . . refuses to disclose the identity of the primary host and site owner. In this fashion Cloudflare acts as a firewall protecting pirate sites and their hosts from legal recourse by copyright owners."[ref]ALS Scan v. Cloudflare, Inc at 2[/ref]

ALS Scan claims it sent "numerous" notices to Cloudflare regarding the infringements being perpetrated by Cloudflare clients, but Cloudflare ignored the notices and continued to provide services to the pirate sites.[ref]ALS Scan v. Cloudflare, Inc at 2[/ref]

The Court, in a previous ruling, dismissed most of the case, but let the claim for contributory infringement stand.

"Plaintiff had plausibly pled secondary liability based on a material contribution theory. (Citation omitted) The Court reasoned that the FAC's allegations that Cloudflare's CDN services made it faster and easier for users to access infringing images, and that consumers seeking access to infringing images retrieved the images from the closest Cloudflare data center rather than the primary host, were sufficient to state a claim for material contribution under Ninth Circuit precedent."[ref]Id. at 2-3[/ref]

Cloudflare sought to have the remaining case against them tossed out of court. Cloudflare put forth two grounds:

- Except for one website, all the pirate websites were locate outside the United States, so U.S. copyright law did not apply.

- Cloudflare's activities constituted fair use.

- The copies are mirror image copies, not transformative, and were made for a commercial purpose.[ref]Id. at 22[/ref]

- The original works were artistic works created for "aesthetic value" (failing to mention, of course, that the images are porn)[ref]Id. at 23[/ref]

- The third factor does not weigh in favor of either party as "the function to which the images were put required full replication."[ref]Id. at 24[/ref]

- "To allow the creation of cache copies on domestic servers would undoubtedly harm the market for Plaintiff's images because it would enhance the infringing sites' ability to reach users who would otherwise need to purchase access to the images from Plaintiff."[ref]Id.[/ref]

No Subjects

On June 9, 2017, a District Court Judge in California denied a Motion to Dismiss claiming that a "mash-up" of Dr. Seuss and Star Trek was fair use.[ref]Dr. Seuss Enterprises v. ComicMix LLC, 2017 WL 2505007 District Court for the Southern District of CA[/ref] The book, titled Oh, the Places You'll Boldly Go!, attempted to "mash-up" (or should that be "mind meld"?) Oh, The Places You'll Go! from the legendary children's book author with various elements of the fictional universe of Star Trek. It is worth noting at the outset, that one of the Defendants responsible for the mash-up is David Gerrold, writer of the famous Star Trek episode "The Trouble with Tribbles."[ref]The Trouble with Tribbles[/ref]

So wouldn't a very experienced author know that they were getting into trouble? It seems so. Their Kickstarter page contained this caveat:

"While we firmly believe that our parody, created with love and affection, fully falls within the boundary of fair use, there may be some people who believe that this might be in violation of their intellectual property rights. And we may have to spend time and money proving it to people in black robes. And we may even lose that."[ref]Dr. Seuss Enterprises v. ComicMix LLC, at 1[/ref]

As Mr. Spock would say…this appears to be logical.

Yet, there is this strange assertion on the books copyright page:

"Copyright Disclaimer under section 107 of the Copyright Act 1976, allowance is made for ‘fair use' for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, education, research, and parody."[ref]Id.[/ref]

The problem with this is that it's not true. Nowhere in Section 107 does the word "parody" appear. Certainly parody, as an element of free speech can be fair use, but not all claimed parodies are in fact fair use. And as we have seen before, simply calling something a "parody" or "fair use" does not make it so.[ref]If You Make it "Porn," Does that Make it a Parody?[/ref]

In fact, Dr. Seuss Enterprises has been down this road before, and in the very same District Court that now considers this case. That case pitted Dr. Seuss against an alleged "parody" of the O.J. Simpson trial, all written in the style of Dr. Seuss, resulting in a book The Cat NOT in the Hat! A Parody by Dr. Juice.[ref]Dr. Seuss Enterprises v Penguin Books, 109 F3rd 1394 Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals 1997[/ref]

As previously recounted by this blog:

"No actual text from any of Dr. Seuss' works were used, only that the words were written in a similar style. For example instead of ‘One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Blue Fish' the offending work served up ‘One Knife? Two Knife? Red Knife Dead Wife.' The design of the book's cover was imitated, yet the only element that was copied directly was the scrunched up stove-pipe hat worn by the Cat. The cover of the book plainly stated it was ‘a parody' attributed to a ‘Dr. Juice,' yet another play on words that had the dual effect of sounding like ‘Seuss' but also playing upon Simpson's nickname as a pro football player, ‘The Juice.' The trial court, affirmed on appeal, held that none of this was a ‘transformative use.' Further, despite the fact that the Defendant's book was clearly labelled in large type ‘a parody' (thus one would not mistake one book for the other) and the rather obvious fact that the two works could never conceivably compete with each other in the marketplace (you would never give your six year old The Cat Not in the Hat), the 9th Circuit summarily dismissed this point by stating that the Defendants had failed to provide the necessary evidence on this point, and blithely stated that the District Court finding was not ‘clearly erroneous.' I also suppose neither Court ever considered the fact that whatever copying was done was pretty much de minimus. My best guess? Both the trial Court and the Appellate Court found the book to be in poor taste and ruled accordingly."[ref]Marching Bravely Into the Quagmire: The Complete Mess that the "Transformative" Test Has Made of Fair Use[/ref]

So this case, with extensive copying, should be a slam dunk, right? You'd be mistaken about that.

Quite surprisingly, the Judge here basically ignores Cat NOT in the Hat. The Court makes a primary citation to the Cat NOT in the Hat case only once in the entire opinion. Further, this mention is for the unremarkable proposition that the Court can resolve fair use issues on a Motion to Dismiss.[ref]Dr. Seuss Enterprises v. ComicMix LLC, at 3[/ref] Interestingly, the Plaintiffs opposed hearing the fair use claim on the Motion to Dismiss, objecting that proof of "market harm" under factor four will require discovery.[ref]Id.[/ref] We will return to this point later.

The Judge leads off by concluding that, despite the protestations of the Defendants, Oh, The Places You'll Boldly Go!, to the contrary, OTPYBG is not a parody.

"Such works [mash ups] may, of course, also be parodies when they juxtapose the underlying works in such a way that it creates ‘comic effect or ridicule.' (citation omitted) However, there is no such juxtaposition here; Boldly merely uses Go!'s illustration style and story format as a means of conveying particular adventures and tropes from the Star Trek canon. And although Defendants argue generally that ‘Boldly uses Dr. Seuss's own works in service of a group-oriented counterpoint to the Go! individualist ideal[,]' (citation omitted), the Court cannot conclude that such a ‘parodic character may reasonably be perceived.'"[ref]Id. at 4[/ref]

Yet, because this is a fair use case, we once again find ourselves stuck in the quagmire of "transformative use."[ref]Marching Bravely Into the Quagmire: The Complete Mess that the "Transformative" Test Has Made of Fair Use[/ref]

"But although Boldly fails to qualify as a parody it is no doubt transformative. In particular, it combines into a completely unique work the two disparate worlds of Dr. Seuss and Star Trek."[ref]Dr. Seuss Enterprises v. ComicMix LLC, at 4[/ref]

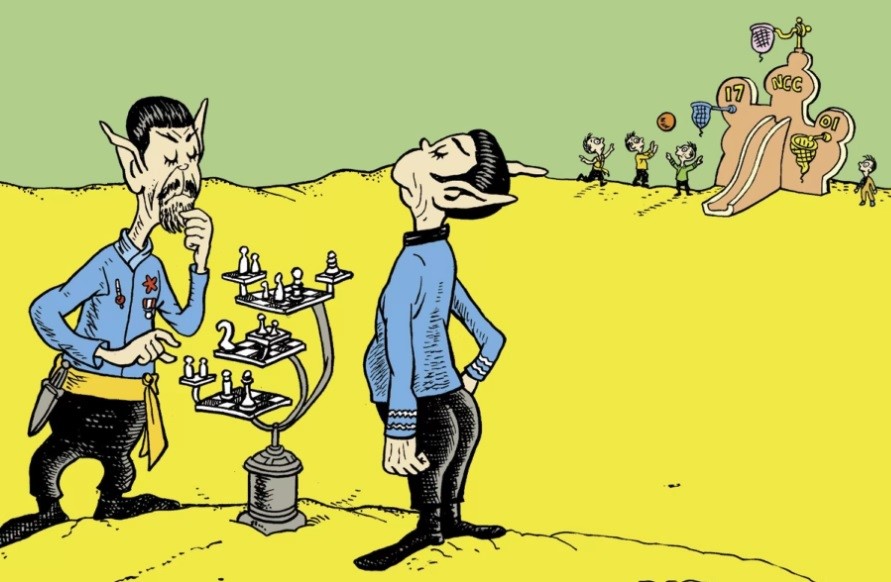

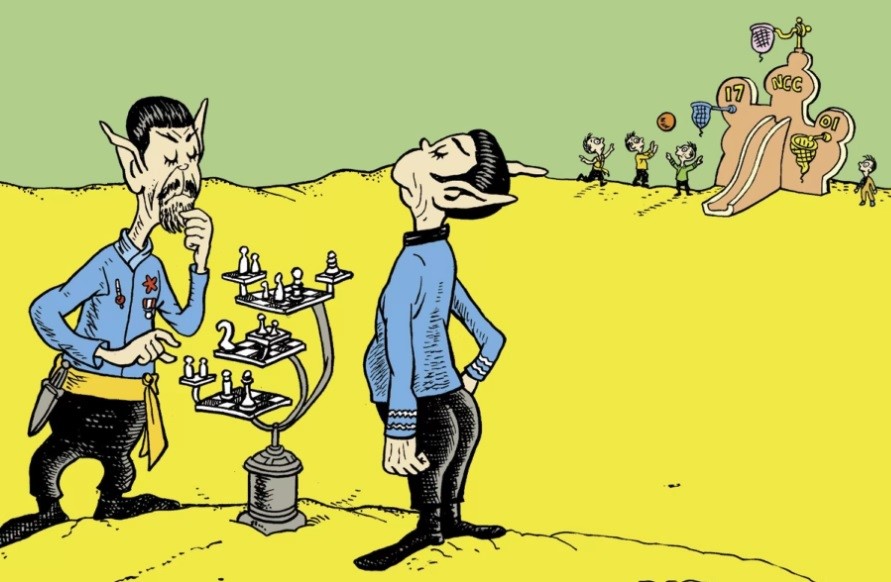

"Go!'s rhyming lines and striking images, as well as other Dr. Seuss works, are often copied by Boldly, but the copied elements are always interspersed with original writing and illustrations that transform Go!'s pages into repurposed, Star-Trek—centric ones."[ref]Id.[/ref] To get a sense of what the Judge is talking about, here is an illustration specifically discussed in the opinion:

The illustration style is clearly that of Dr. Seuss, right down to the lack of straight lines as evidenced by the droopy baskets in the background. But the characters in the foreground are clearly Vulcans and the NCC 1701 is a reference to the Enterprise.

Wait a second here. Remember The Cat NOT in the Hat? There was virtually no copying of anything from a Dr. Seuss book, save for the Cat's trademark scrunched-up stove pipe hat. The 9th Circuit, in binding precedent on this Court ruled this to be not transformative. But now faced with extensive copying from the very same author, the District Court rules this is transformative. So transformative is this use that the very commercial purpose of the Defendants' work did not prevent a finding by the Court that the "Purpose and Character" of the use favored the Defendants.[ref]Id.[/ref]

The Court finds the second factor the "nature of the work used" favors the Plaintiffs only slightly.[ref]Id. at 5[/ref]

As to the third factor, the "amount and substantiality of the portion used," the Court once again is unable to escape the transformative quagmire.

"In the present case, there is no dispute that Boldly copies many aspects of Go!'s and other Dr. Seuss illustrations. However Boldly does not copy them in their entirety; each is infused with new meaning and additional illustrations that reframe the Seuss images from a unique Star-Trek viewpoint. Nor does Boldly copy more than is necessary to accomplish its transformative purpose."[ref]Id.[/ref]

But the case cited to for this proposition, the well-known Campbell v. Acuff-Rose case, is about parody. The Court has already ruled that OTPYBG is not a parody, but now reaches back to treat it as if it is a parody. This confusion leads to the ruling that this factor weighs in favor of the Defendants.[ref]Id.[/ref]

Now comes the most curious part of the opinion. In analyzing the "effect of the use on the potential market," the Court claims to be hamstrung by its decision to rule on fair use at this very early point in the case. The Court rules correctly that "Boldly does not substitute for the original and serves a different market function than Go!"[ref]Id.[/ref] but that:

"In the current procedural posture Defendants are at a clear disadvantage under this factor's required analysis… In particular, Plaintiff's Complaint alleges that "[i]t is not uncommon for DSE to license" its works, including in "collaborations with other rights holders." (citation omitted) And although Defendants might well be able to ultimately disprove this statement as it applies works of Boldly's type, there is not currently any record evidence on this point."[ref]Id.[/ref]

Which is exactly the reason why the Plaintiffs objected to hearing the fair use claim on a Motion to Dismiss!

Nevertheless, this works out for Dr. Seuss, since the Judge must at this stage assume all the facts pled by the Plaintiff are true, the allegations of the complaint regarding negative market effect tip factor four in favor of the Plaintiff.

"Ultimately, given the procedural posture of this motion and near-perfect balancing of the factors, the Court DENIES (emphasis original) Defendants' Motion to Dismiss. Specifically, without relevant evidence regarding factor four the Court concludes that Defendants' fair use defense currently fails as a matter of law."[ref]Id. at 6[/ref]

The use by the Court of the word "currently" leads me to believe that the Court will reconsider the question of fair use somewhere down the line. So, the copyright portion of the case will proceed, but remember, since fair use is an affirmative defense, the Defendants will bear the burden of proof. But the Court considers this a close case.

"This case presents an important question regarding the emerging ‘mash-up' culture where artists combine two independent works in a new and unique way… Applying the fair use factors in the manner Plaintiff outlines would almost always preclude a finding of fair use under these circumstances. However, if fair use was not viable in a case such as this, an entire body of highly creative work would be effectively foreclosed. Of course that is not to say that all mash-ups will or should succeed on a fair use defense; the level of creativity, variance from the original source materials, resulting commentary, and intended market will necessarily make evaluation particularized. In this regard, mash-ups are no different than the usual fair use case. However, in this particular case the Court has before it a highly transformative work that takes no more than necessary to accomplish its transformative purpose and will not impinge on the original market for Plaintiff's underlying work."[ref]Id.[/ref]

Here's the problem with this analysis. What the Court has before it is a classic derivative work as described by 17 USC 106(2). This is the definition:

"A ‘derivative work' is a work based upon one or more preexisting works, such as a translation, musical arrangement, dramatization, fictionalization, motion picture version, sound recording, art reproduction, abridgment, condensation, or any other form in which a work may be recast, transformed, or adapted."[ref]17 USC 101[/ref]

See? The word "transformed" is right there in the definition of what a derivative work is. The right to "transform" the work is my exclusive right as a copyright holder. You do not have the right to "transform" my work without my permission. It's right there in the plain text of the Copyright Act.

Remember, Campbell was a case of parody. The Court here has already ruled that OTPYBG is not a parody. There are certain free speech components to making a parody, and you have a right to free speech. You do not have a "right" to "transform" my work. Under the copyright act, that is my right. It doesn't matter what the "emerging mash-up culture" thinks. Re-mixing is not a right.[ref]Remixing is Not a Right[/ref]

Yet, the Defendants trumpeted this ruling against them on their website as a victory![ref]ComicMix Vindicated in Dr. Seuss Lawsuit Over Literary Mash-Up; Judge Dismisses Trademark Claims, Copyright Claim Will "Boldly Go Forward"[/ref] "Vindication" screams the headline. Later this was amended to note that only the trademark portions got dismissed, not the copyright claims, which of course, go forward.

So guys, right now, the only place you're going to "boldly go" is back to the courthouse.

The illustration style is clearly that of Dr. Seuss, right down to the lack of straight lines as evidenced by the droopy baskets in the background. But the characters in the foreground are clearly Vulcans and the NCC 1701 is a reference to the Enterprise.

Wait a second here. Remember The Cat NOT in the Hat? There was virtually no copying of anything from a Dr. Seuss book, save for the Cat's trademark scrunched-up stove pipe hat. The 9th Circuit, in binding precedent on this Court ruled this to be not transformative. But now faced with extensive copying from the very same author, the District Court rules this is transformative. So transformative is this use that the very commercial purpose of the Defendants' work did not prevent a finding by the Court that the "Purpose and Character" of the use favored the Defendants.[ref]Id.[/ref]

The Court finds the second factor the "nature of the work used" favors the Plaintiffs only slightly.[ref]Id. at 5[/ref]

As to the third factor, the "amount and substantiality of the portion used," the Court once again is unable to escape the transformative quagmire.

"In the present case, there is no dispute that Boldly copies many aspects of Go!'s and other Dr. Seuss illustrations. However Boldly does not copy them in their entirety; each is infused with new meaning and additional illustrations that reframe the Seuss images from a unique Star-Trek viewpoint. Nor does Boldly copy more than is necessary to accomplish its transformative purpose."[ref]Id.[/ref]

But the case cited to for this proposition, the well-known Campbell v. Acuff-Rose case, is about parody. The Court has already ruled that OTPYBG is not a parody, but now reaches back to treat it as if it is a parody. This confusion leads to the ruling that this factor weighs in favor of the Defendants.[ref]Id.[/ref]

Now comes the most curious part of the opinion. In analyzing the "effect of the use on the potential market," the Court claims to be hamstrung by its decision to rule on fair use at this very early point in the case. The Court rules correctly that "Boldly does not substitute for the original and serves a different market function than Go!"[ref]Id.[/ref] but that:

"In the current procedural posture Defendants are at a clear disadvantage under this factor's required analysis… In particular, Plaintiff's Complaint alleges that "[i]t is not uncommon for DSE to license" its works, including in "collaborations with other rights holders." (citation omitted) And although Defendants might well be able to ultimately disprove this statement as it applies works of Boldly's type, there is not currently any record evidence on this point."[ref]Id.[/ref]

Which is exactly the reason why the Plaintiffs objected to hearing the fair use claim on a Motion to Dismiss!

Nevertheless, this works out for Dr. Seuss, since the Judge must at this stage assume all the facts pled by the Plaintiff are true, the allegations of the complaint regarding negative market effect tip factor four in favor of the Plaintiff.

"Ultimately, given the procedural posture of this motion and near-perfect balancing of the factors, the Court DENIES (emphasis original) Defendants' Motion to Dismiss. Specifically, without relevant evidence regarding factor four the Court concludes that Defendants' fair use defense currently fails as a matter of law."[ref]Id. at 6[/ref]

The use by the Court of the word "currently" leads me to believe that the Court will reconsider the question of fair use somewhere down the line. So, the copyright portion of the case will proceed, but remember, since fair use is an affirmative defense, the Defendants will bear the burden of proof. But the Court considers this a close case.

"This case presents an important question regarding the emerging ‘mash-up' culture where artists combine two independent works in a new and unique way… Applying the fair use factors in the manner Plaintiff outlines would almost always preclude a finding of fair use under these circumstances. However, if fair use was not viable in a case such as this, an entire body of highly creative work would be effectively foreclosed. Of course that is not to say that all mash-ups will or should succeed on a fair use defense; the level of creativity, variance from the original source materials, resulting commentary, and intended market will necessarily make evaluation particularized. In this regard, mash-ups are no different than the usual fair use case. However, in this particular case the Court has before it a highly transformative work that takes no more than necessary to accomplish its transformative purpose and will not impinge on the original market for Plaintiff's underlying work."[ref]Id.[/ref]

Here's the problem with this analysis. What the Court has before it is a classic derivative work as described by 17 USC 106(2). This is the definition:

"A ‘derivative work' is a work based upon one or more preexisting works, such as a translation, musical arrangement, dramatization, fictionalization, motion picture version, sound recording, art reproduction, abridgment, condensation, or any other form in which a work may be recast, transformed, or adapted."[ref]17 USC 101[/ref]

See? The word "transformed" is right there in the definition of what a derivative work is. The right to "transform" the work is my exclusive right as a copyright holder. You do not have the right to "transform" my work without my permission. It's right there in the plain text of the Copyright Act.

Remember, Campbell was a case of parody. The Court here has already ruled that OTPYBG is not a parody. There are certain free speech components to making a parody, and you have a right to free speech. You do not have a "right" to "transform" my work. Under the copyright act, that is my right. It doesn't matter what the "emerging mash-up culture" thinks. Re-mixing is not a right.[ref]Remixing is Not a Right[/ref]

Yet, the Defendants trumpeted this ruling against them on their website as a victory![ref]ComicMix Vindicated in Dr. Seuss Lawsuit Over Literary Mash-Up; Judge Dismisses Trademark Claims, Copyright Claim Will "Boldly Go Forward"[/ref] "Vindication" screams the headline. Later this was amended to note that only the trademark portions got dismissed, not the copyright claims, which of course, go forward.

So guys, right now, the only place you're going to "boldly go" is back to the courthouse.

The illustration style is clearly that of Dr. Seuss, right down to the lack of straight lines as evidenced by the droopy baskets in the background. But the characters in the foreground are clearly Vulcans and the NCC 1701 is a reference to the Enterprise.

Wait a second here. Remember The Cat NOT in the Hat? There was virtually no copying of anything from a Dr. Seuss book, save for the Cat's trademark scrunched-up stove pipe hat. The 9th Circuit, in binding precedent on this Court ruled this to be not transformative. But now faced with extensive copying from the very same author, the District Court rules this is transformative. So transformative is this use that the very commercial purpose of the Defendants' work did not prevent a finding by the Court that the "Purpose and Character" of the use favored the Defendants.[ref]Id.[/ref]

The Court finds the second factor the "nature of the work used" favors the Plaintiffs only slightly.[ref]Id. at 5[/ref]

As to the third factor, the "amount and substantiality of the portion used," the Court once again is unable to escape the transformative quagmire.

"In the present case, there is no dispute that Boldly copies many aspects of Go!'s and other Dr. Seuss illustrations. However Boldly does not copy them in their entirety; each is infused with new meaning and additional illustrations that reframe the Seuss images from a unique Star-Trek viewpoint. Nor does Boldly copy more than is necessary to accomplish its transformative purpose."[ref]Id.[/ref]

But the case cited to for this proposition, the well-known Campbell v. Acuff-Rose case, is about parody. The Court has already ruled that OTPYBG is not a parody, but now reaches back to treat it as if it is a parody. This confusion leads to the ruling that this factor weighs in favor of the Defendants.[ref]Id.[/ref]

Now comes the most curious part of the opinion. In analyzing the "effect of the use on the potential market," the Court claims to be hamstrung by its decision to rule on fair use at this very early point in the case. The Court rules correctly that "Boldly does not substitute for the original and serves a different market function than Go!"[ref]Id.[/ref] but that:

"In the current procedural posture Defendants are at a clear disadvantage under this factor's required analysis… In particular, Plaintiff's Complaint alleges that "[i]t is not uncommon for DSE to license" its works, including in "collaborations with other rights holders." (citation omitted) And although Defendants might well be able to ultimately disprove this statement as it applies works of Boldly's type, there is not currently any record evidence on this point."[ref]Id.[/ref]

Which is exactly the reason why the Plaintiffs objected to hearing the fair use claim on a Motion to Dismiss!

Nevertheless, this works out for Dr. Seuss, since the Judge must at this stage assume all the facts pled by the Plaintiff are true, the allegations of the complaint regarding negative market effect tip factor four in favor of the Plaintiff.

"Ultimately, given the procedural posture of this motion and near-perfect balancing of the factors, the Court DENIES (emphasis original) Defendants' Motion to Dismiss. Specifically, without relevant evidence regarding factor four the Court concludes that Defendants' fair use defense currently fails as a matter of law."[ref]Id. at 6[/ref]

The use by the Court of the word "currently" leads me to believe that the Court will reconsider the question of fair use somewhere down the line. So, the copyright portion of the case will proceed, but remember, since fair use is an affirmative defense, the Defendants will bear the burden of proof. But the Court considers this a close case.

"This case presents an important question regarding the emerging ‘mash-up' culture where artists combine two independent works in a new and unique way… Applying the fair use factors in the manner Plaintiff outlines would almost always preclude a finding of fair use under these circumstances. However, if fair use was not viable in a case such as this, an entire body of highly creative work would be effectively foreclosed. Of course that is not to say that all mash-ups will or should succeed on a fair use defense; the level of creativity, variance from the original source materials, resulting commentary, and intended market will necessarily make evaluation particularized. In this regard, mash-ups are no different than the usual fair use case. However, in this particular case the Court has before it a highly transformative work that takes no more than necessary to accomplish its transformative purpose and will not impinge on the original market for Plaintiff's underlying work."[ref]Id.[/ref]

Here's the problem with this analysis. What the Court has before it is a classic derivative work as described by 17 USC 106(2). This is the definition:

"A ‘derivative work' is a work based upon one or more preexisting works, such as a translation, musical arrangement, dramatization, fictionalization, motion picture version, sound recording, art reproduction, abridgment, condensation, or any other form in which a work may be recast, transformed, or adapted."[ref]17 USC 101[/ref]

See? The word "transformed" is right there in the definition of what a derivative work is. The right to "transform" the work is my exclusive right as a copyright holder. You do not have the right to "transform" my work without my permission. It's right there in the plain text of the Copyright Act.

Remember, Campbell was a case of parody. The Court here has already ruled that OTPYBG is not a parody. There are certain free speech components to making a parody, and you have a right to free speech. You do not have a "right" to "transform" my work. Under the copyright act, that is my right. It doesn't matter what the "emerging mash-up culture" thinks. Re-mixing is not a right.[ref]Remixing is Not a Right[/ref]

Yet, the Defendants trumpeted this ruling against them on their website as a victory![ref]ComicMix Vindicated in Dr. Seuss Lawsuit Over Literary Mash-Up; Judge Dismisses Trademark Claims, Copyright Claim Will "Boldly Go Forward"[/ref] "Vindication" screams the headline. Later this was amended to note that only the trademark portions got dismissed, not the copyright claims, which of course, go forward.

So guys, right now, the only place you're going to "boldly go" is back to the courthouse.

The illustration style is clearly that of Dr. Seuss, right down to the lack of straight lines as evidenced by the droopy baskets in the background. But the characters in the foreground are clearly Vulcans and the NCC 1701 is a reference to the Enterprise.

Wait a second here. Remember The Cat NOT in the Hat? There was virtually no copying of anything from a Dr. Seuss book, save for the Cat's trademark scrunched-up stove pipe hat. The 9th Circuit, in binding precedent on this Court ruled this to be not transformative. But now faced with extensive copying from the very same author, the District Court rules this is transformative. So transformative is this use that the very commercial purpose of the Defendants' work did not prevent a finding by the Court that the "Purpose and Character" of the use favored the Defendants.[ref]Id.[/ref]

The Court finds the second factor the "nature of the work used" favors the Plaintiffs only slightly.[ref]Id. at 5[/ref]

As to the third factor, the "amount and substantiality of the portion used," the Court once again is unable to escape the transformative quagmire.

"In the present case, there is no dispute that Boldly copies many aspects of Go!'s and other Dr. Seuss illustrations. However Boldly does not copy them in their entirety; each is infused with new meaning and additional illustrations that reframe the Seuss images from a unique Star-Trek viewpoint. Nor does Boldly copy more than is necessary to accomplish its transformative purpose."[ref]Id.[/ref]

But the case cited to for this proposition, the well-known Campbell v. Acuff-Rose case, is about parody. The Court has already ruled that OTPYBG is not a parody, but now reaches back to treat it as if it is a parody. This confusion leads to the ruling that this factor weighs in favor of the Defendants.[ref]Id.[/ref]

Now comes the most curious part of the opinion. In analyzing the "effect of the use on the potential market," the Court claims to be hamstrung by its decision to rule on fair use at this very early point in the case. The Court rules correctly that "Boldly does not substitute for the original and serves a different market function than Go!"[ref]Id.[/ref] but that:

"In the current procedural posture Defendants are at a clear disadvantage under this factor's required analysis… In particular, Plaintiff's Complaint alleges that "[i]t is not uncommon for DSE to license" its works, including in "collaborations with other rights holders." (citation omitted) And although Defendants might well be able to ultimately disprove this statement as it applies works of Boldly's type, there is not currently any record evidence on this point."[ref]Id.[/ref]

Which is exactly the reason why the Plaintiffs objected to hearing the fair use claim on a Motion to Dismiss!

Nevertheless, this works out for Dr. Seuss, since the Judge must at this stage assume all the facts pled by the Plaintiff are true, the allegations of the complaint regarding negative market effect tip factor four in favor of the Plaintiff.

"Ultimately, given the procedural posture of this motion and near-perfect balancing of the factors, the Court DENIES (emphasis original) Defendants' Motion to Dismiss. Specifically, without relevant evidence regarding factor four the Court concludes that Defendants' fair use defense currently fails as a matter of law."[ref]Id. at 6[/ref]

The use by the Court of the word "currently" leads me to believe that the Court will reconsider the question of fair use somewhere down the line. So, the copyright portion of the case will proceed, but remember, since fair use is an affirmative defense, the Defendants will bear the burden of proof. But the Court considers this a close case.

"This case presents an important question regarding the emerging ‘mash-up' culture where artists combine two independent works in a new and unique way… Applying the fair use factors in the manner Plaintiff outlines would almost always preclude a finding of fair use under these circumstances. However, if fair use was not viable in a case such as this, an entire body of highly creative work would be effectively foreclosed. Of course that is not to say that all mash-ups will or should succeed on a fair use defense; the level of creativity, variance from the original source materials, resulting commentary, and intended market will necessarily make evaluation particularized. In this regard, mash-ups are no different than the usual fair use case. However, in this particular case the Court has before it a highly transformative work that takes no more than necessary to accomplish its transformative purpose and will not impinge on the original market for Plaintiff's underlying work."[ref]Id.[/ref]

Here's the problem with this analysis. What the Court has before it is a classic derivative work as described by 17 USC 106(2). This is the definition:

"A ‘derivative work' is a work based upon one or more preexisting works, such as a translation, musical arrangement, dramatization, fictionalization, motion picture version, sound recording, art reproduction, abridgment, condensation, or any other form in which a work may be recast, transformed, or adapted."[ref]17 USC 101[/ref]

See? The word "transformed" is right there in the definition of what a derivative work is. The right to "transform" the work is my exclusive right as a copyright holder. You do not have the right to "transform" my work without my permission. It's right there in the plain text of the Copyright Act.

Remember, Campbell was a case of parody. The Court here has already ruled that OTPYBG is not a parody. There are certain free speech components to making a parody, and you have a right to free speech. You do not have a "right" to "transform" my work. Under the copyright act, that is my right. It doesn't matter what the "emerging mash-up culture" thinks. Re-mixing is not a right.[ref]Remixing is Not a Right[/ref]

Yet, the Defendants trumpeted this ruling against them on their website as a victory![ref]ComicMix Vindicated in Dr. Seuss Lawsuit Over Literary Mash-Up; Judge Dismisses Trademark Claims, Copyright Claim Will "Boldly Go Forward"[/ref] "Vindication" screams the headline. Later this was amended to note that only the trademark portions got dismissed, not the copyright claims, which of course, go forward.

So guys, right now, the only place you're going to "boldly go" is back to the courthouse.

No Subjects

Depending on your point of view, the settlement agreement between Flo and Eddie and Sirius XM is looking like sheer genius or fool hardy folly.[ref]Gentlemen, Hedge Your Bets! Inside the Flo and Eddie-SiriusXM Settlement[/ref] On June 5, 2017, a Federal Judge in the Northern District of Illinois ruled that pre-1972 sound recordings did not have performance rights under Illinois law.[ref]Sheridan v. iHeartMedia 2017 WL 2424217, District Court for the Northern District of Illinois 2017.[/ref]

The Plaintiffs in this case were not Flo and Eddie. The Plaintiffs in this case were Arthur and Barbara Sheridan, the owners of numerous sound recordings of the 1950's and 1960's, including those made by such popular artists as the Flamingos and the Moonglows.[ref]Id. at 1[/ref] Yet, like Flo and Eddie, this was filed as a class action, meaning if the Plaintiffs were successful, the rather large body of those persons owning rights in pre-1972 sound recordings would stand to benefit.

In dismissing the case, the Court never reached the issue of whether common law copyright under Illinois law included the right of public performance. Instead, it ruled that whatever common law copyrights the Plaintiffs might have had, that these rights were divested from them by the act of selling copies of the records to the general public. Further, reaching down to an Illinois State Circuit Court case, it also concludes that performance of the sound recordings divested them of common law copyright protection as well.[ref]Id. at 3[/ref]

While supported by case law, this leads the court down the path to a rather curious conundrum. The Court seems to take at face value that common law copyright exists for sound recordings, but in essence rules that the copyright is then waived by any attempt to take advantage of that self-same common law copyright.

In other words, yes you have rights, until you want to use them.

So, consider the plight of the Plaintiffs. What protection can they get for their sound recordings? They can't go to the Copyright Office because Federal law does not recognize that there are any rights in pre-1972 sound recordings. They seem to have common law copyrights, but these rights are then waived by selling copies or performing them over the radio. So basically, the Plaintiffs are limited to sitting in the confines of their own home playing their own recordings (not too loudly) for their own amusement.

That's not much of a right.

Further undercutting the case was the fact that the Plaintiffs relied heavily on New York case law regarding common law copyrights in sound recordings. As recounted earlier on the blog, the New York Court of Appeals proceeded to throw them under the bus[ref]New York Court of Appeals Says No Performance Rights for Flo and Eddie: "Poof" Goes Five Million Dollars[/ref] after the briefs were submitted here.

The Plaintiffs alleged other claims, including unfair trade practices, but these theories fared no better.

"‘The recording industry and broadcasters existed in a sort of symbiotic relationship wherein the recording industry recognized that radio airplay was free advertising that lured consumers to retail stores where they would purchase recordings. And in return, the broadcasters paid no fees, licensing or otherwise, to the recording industry for the performance of those recordings.' (citation omitted) Even today, this system survives largely intact; there is still no requirement that traditional broadcasters pay such royalties. The argument that this long-extant system exacts "draconian"—i.e., fundamentally unfair—costs is not compelling."[ref]Sheridan v. iHeartMedia at 4[/ref]

There's only one problem with this logic. The economics of this "symbiotic relationship" have totally changed. Physical sales have plunged. Revenues from streaming surpass physical sales.[ref]IFPI Global Report: Digital Revenues Surpass Physical for the First Time as Streaming Explodes[/ref] If you click on the link in the footnote you will note that the Billboard article I linked to is over a year old. The old adage that radio plays equals records sales is no longer true.

The Court here, like the New York Court of Appeals sees disaster in ruling otherwise:

"But in the context of broadcasts of sound recordings, where the settled expectation of the industry has for decades been that there is no requirement to pay for the right to broadcast pre-1972 sound recordings, it cannot reasonably be said that it is fundamentally unfair for a broadcaster to operate in conformance with that status quo. To the contrary, disrupting the settled expectations of the entire music industry could unfairly impose substantial costs on myriad industry stakeholders."[ref]Sheridan v. iHeartMedia at 6[/ref]

Wait, aren't copyright holders (as well as taxi drivers, newspapers, bookstores, retail stores etc., etc., etc.) being told all the time that the "disruption" to their industry is a good thing? Now, when the shoe is firmly on the other foot, we are told that to recognize that artists have had certain rights for quite a long time would be too "disruptive." To add insult to injury, the Court cites to an Electronic Frontier Foundation blog post for this proposition, which is hearsay to the Court and should be inadmissible as evidence, especially at the Motion to Dismiss stage.

To the Defendant, iHeartMedia, the glow of this win won't last very long. The company is losing vast sums of money and according to its own reports indicate that it might be bankrupt in the next 12 months.[ref]iHeartMedia Debt Grows, Layoffs Continue Amid Concern for Future[/ref]

Why? Because the streaming companies are "disrupting" its business model.

No Subjects