On March 12, 2019, the Judge in the long-running dispute between the writers of a Dr. Seuss-Star Trek "mash-up" titled "Oh, the Places You'll Boldly Go!" and Dr. Seuss Enterprises granted summary judgement to the Defendants, ruling that OTPYBG was "highly transformative" and fair use.[ref]Dr. Seuss Enterprises L.P. v. ComicMix LLC et al, United Sates District Court for the Southern District of California 2019. No Westlaw cite is currently available. All page cites are to the original order.[/ref]

What made this ruling quite surprising was that:

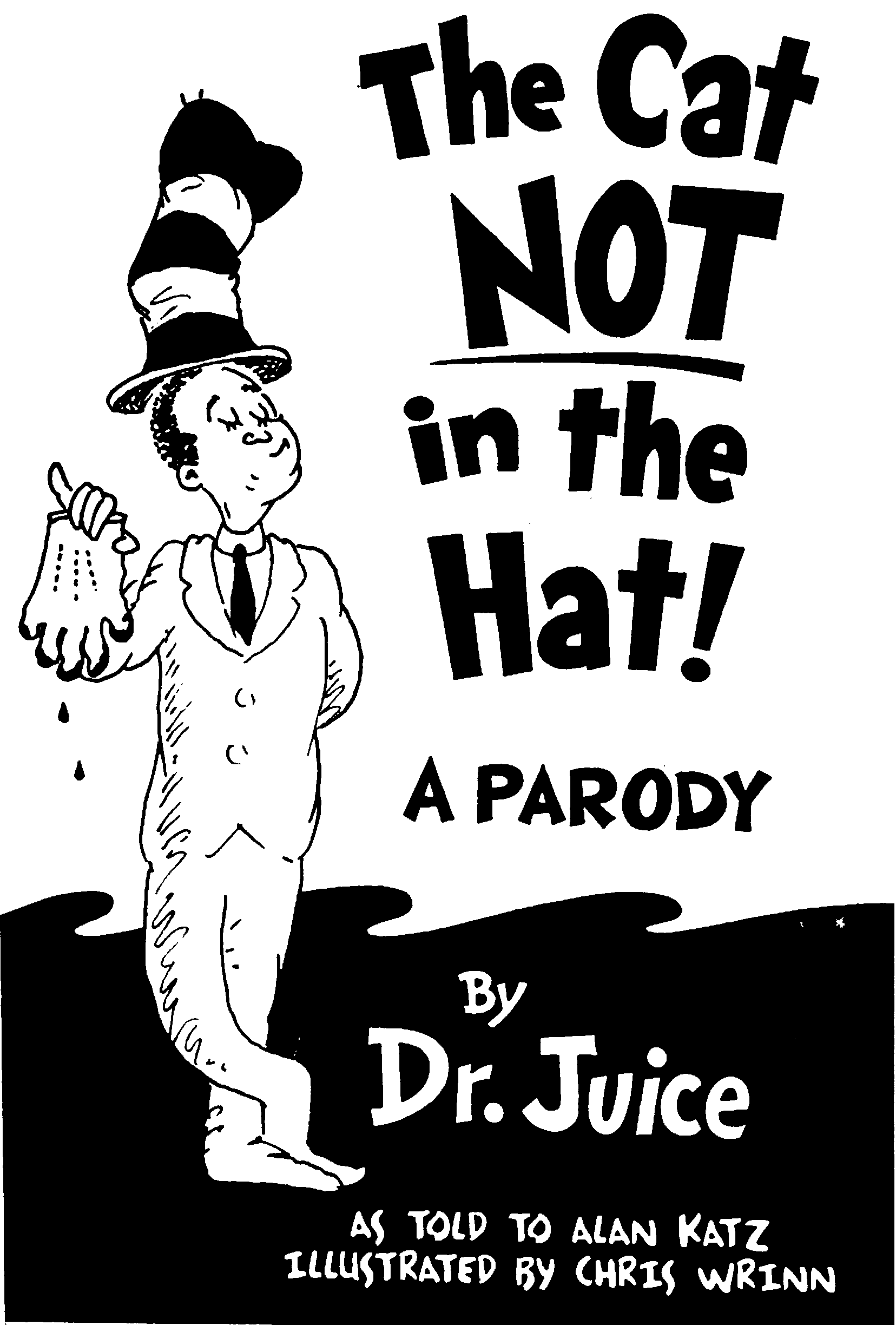

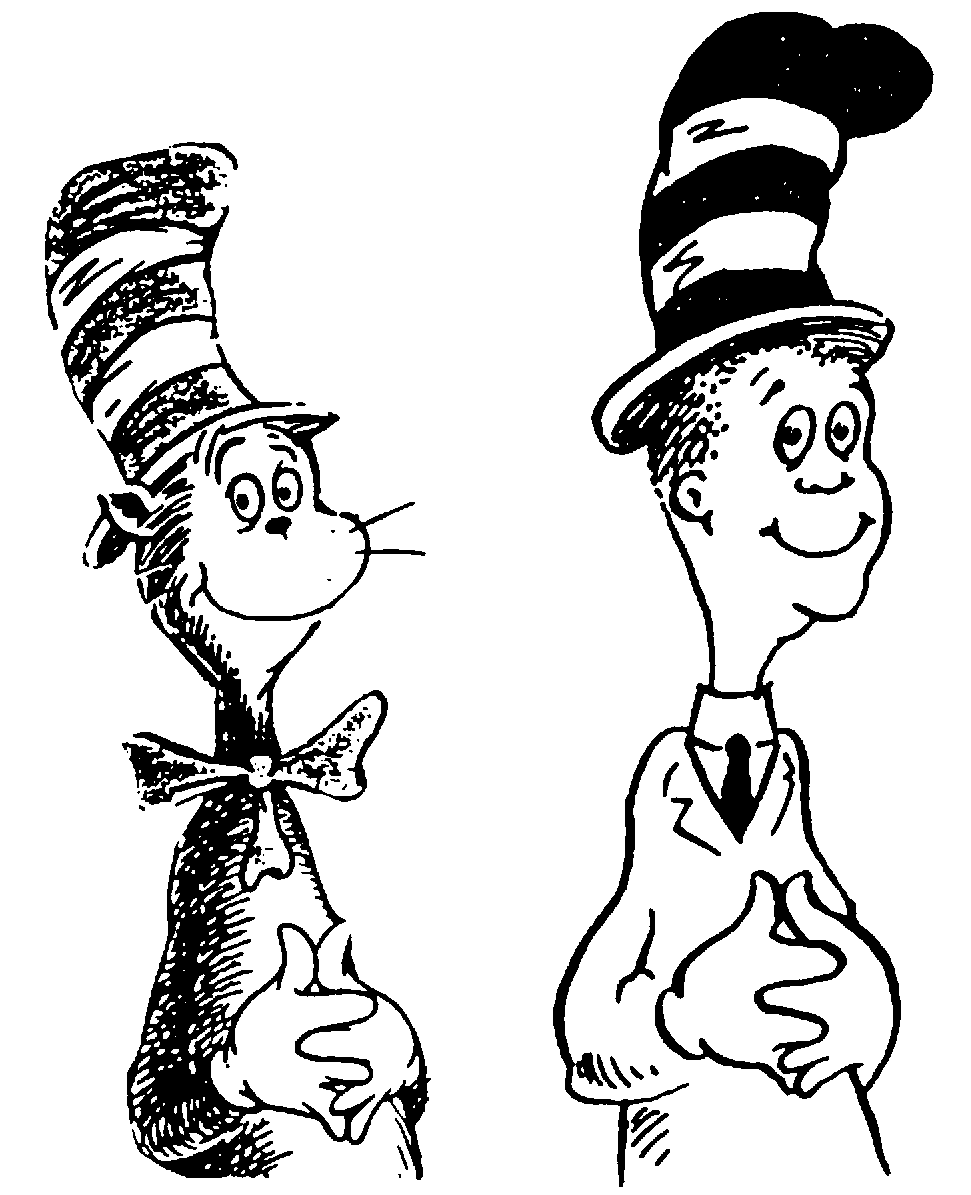

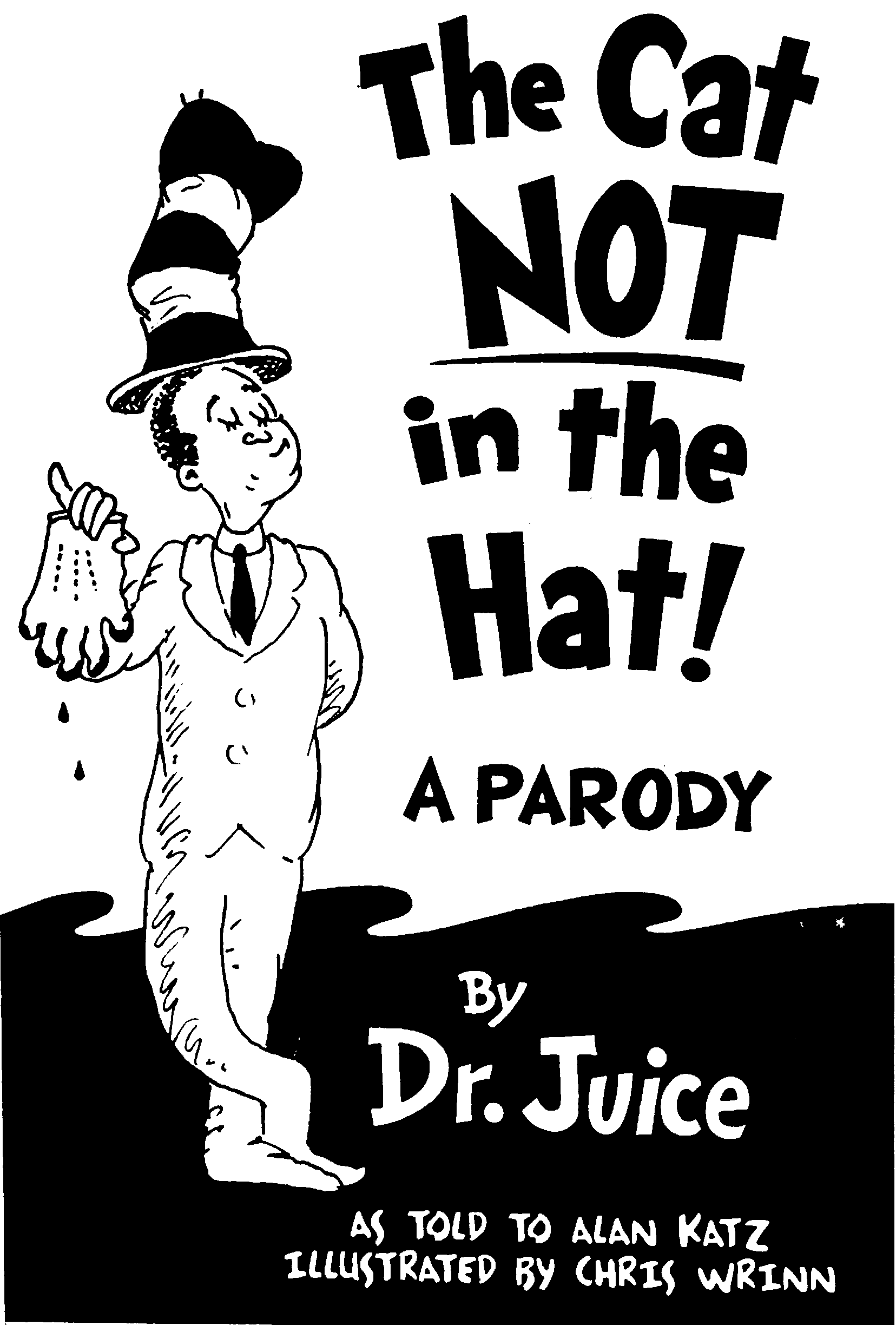

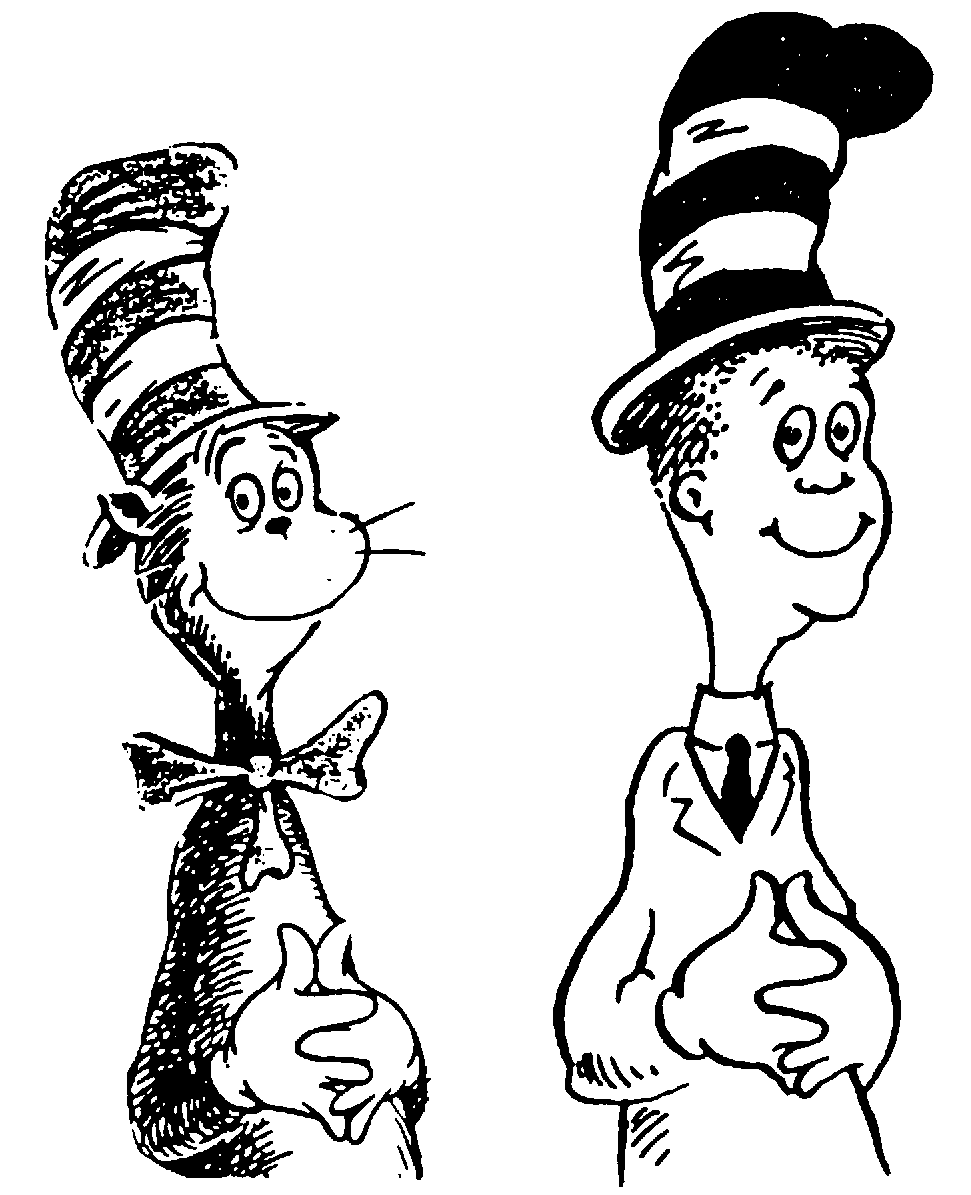

And here is a side by side comparison of The Cat In the Hat and "Dr. Juice" who is the tongue in cheek author of "The Cat NOT in The Hat."

And here is a side by side comparison of The Cat In the Hat and "Dr. Juice" who is the tongue in cheek author of "The Cat NOT in The Hat."

Clearly the intent is to mimic the illustration style of Dr. Seuss. The writing style is also closely imitated.

"The third page reads: "One Knife? / Two Knife? / Red Knife / Dead Wife." This stanza no doubt mimics the first poem in Dr. Seuss' One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish: "One fish / two fish / red fish / blue fish. Black fish / blue fish / old fish / new fish."[ref]Id. at 1401[/ref]

But the extent of the imitation is very slight. Oddly enough, this works against the Defendants.

"These stanzas and the illustrations simply retell the Simpson tale. Although The Cat NOT in the Hat! does broadly mimic Dr. Seuss' characteristic style, it does not hold his style up to ridicule. The stanzas have ‘no critical bearing on the substance or style of' The Cat in the Hat."[ref]Id.[/ref]

"The district court concluded that "The Cat in the Hat" is the central character, appearing in nearly every image of The Cat in the Hat. Penguin and Dove appropriated the Cat's image, copying the Cat's Hat and using the image on the front and back covers and in the text (13 times). We have no doubt that the Cat's image is the highly expressive core of Dr. Seuss' work."[ref]Id. at 1402[/ref]

The Ninth Circuit finally concludes:

"The good will and reputation associated with Dr. Seuss' work is substantial. Because, on the facts presented, Penguin and Dove's use of The Cat in the Hat original was non-transformative, and admittedly commercial, we conclude that market substitution is at least more certain, and market harm may be more readily inferred."[ref]Id. at 1403[/ref]

The last part is really curious. Would you really give a six year old "The Cat NOT in the Hat," instead of the "The Cat in the Hat"? I sincerely doubt it. Also notice that the Court is going to infer market harm on a book that is not being currently sold or distributed because it is subject to a preliminary injunction.[ref]Id. at 1397[/ref]

So now, let us turn to "Oh The Places You'll Boldly Go!"

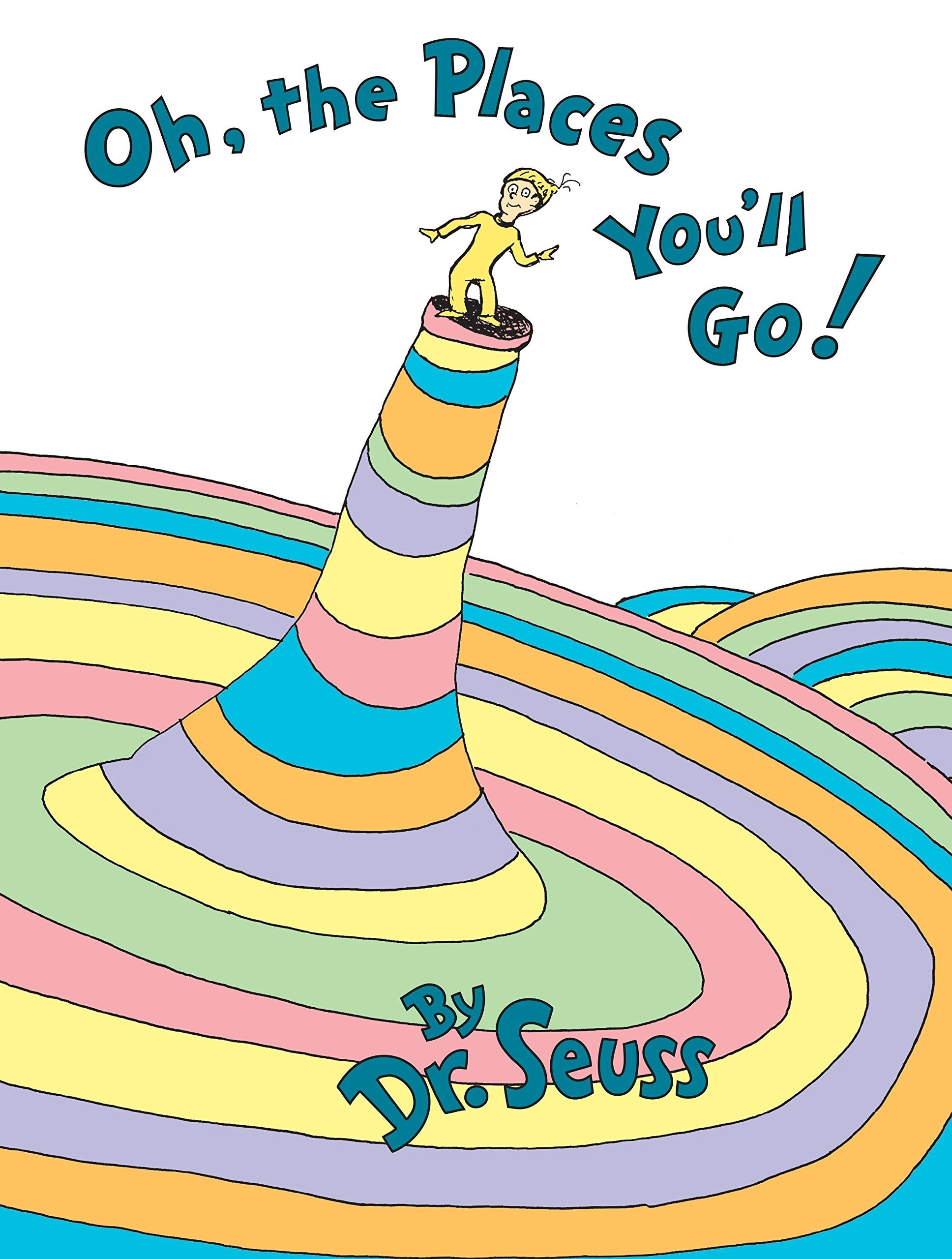

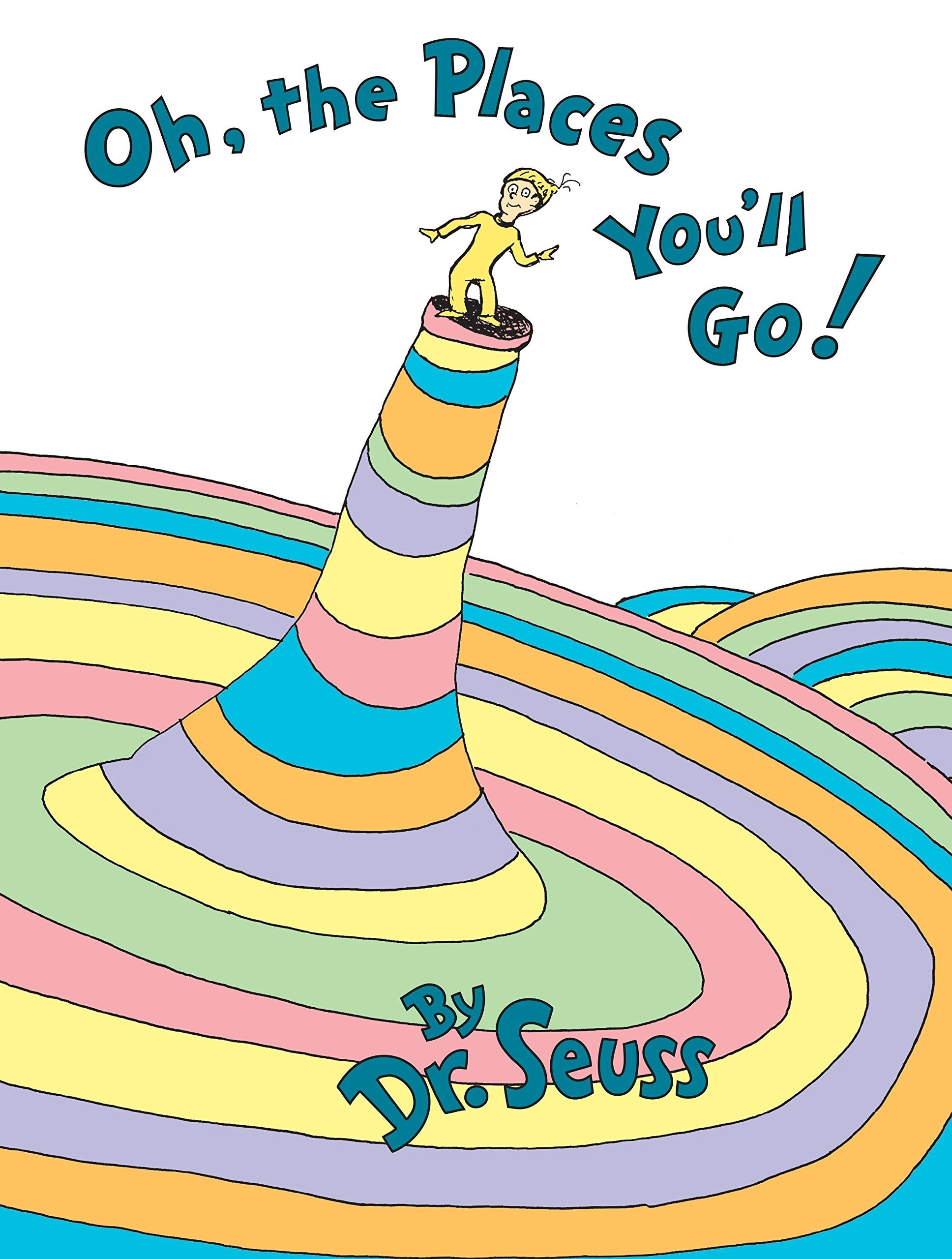

Here is the original Dr. Seuss Cover:

Clearly the intent is to mimic the illustration style of Dr. Seuss. The writing style is also closely imitated.

"The third page reads: "One Knife? / Two Knife? / Red Knife / Dead Wife." This stanza no doubt mimics the first poem in Dr. Seuss' One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish: "One fish / two fish / red fish / blue fish. Black fish / blue fish / old fish / new fish."[ref]Id. at 1401[/ref]

But the extent of the imitation is very slight. Oddly enough, this works against the Defendants.

"These stanzas and the illustrations simply retell the Simpson tale. Although The Cat NOT in the Hat! does broadly mimic Dr. Seuss' characteristic style, it does not hold his style up to ridicule. The stanzas have ‘no critical bearing on the substance or style of' The Cat in the Hat."[ref]Id.[/ref]

"The district court concluded that "The Cat in the Hat" is the central character, appearing in nearly every image of The Cat in the Hat. Penguin and Dove appropriated the Cat's image, copying the Cat's Hat and using the image on the front and back covers and in the text (13 times). We have no doubt that the Cat's image is the highly expressive core of Dr. Seuss' work."[ref]Id. at 1402[/ref]

The Ninth Circuit finally concludes:

"The good will and reputation associated with Dr. Seuss' work is substantial. Because, on the facts presented, Penguin and Dove's use of The Cat in the Hat original was non-transformative, and admittedly commercial, we conclude that market substitution is at least more certain, and market harm may be more readily inferred."[ref]Id. at 1403[/ref]

The last part is really curious. Would you really give a six year old "The Cat NOT in the Hat," instead of the "The Cat in the Hat"? I sincerely doubt it. Also notice that the Court is going to infer market harm on a book that is not being currently sold or distributed because it is subject to a preliminary injunction.[ref]Id. at 1397[/ref]

So now, let us turn to "Oh The Places You'll Boldly Go!"

Here is the original Dr. Seuss Cover:

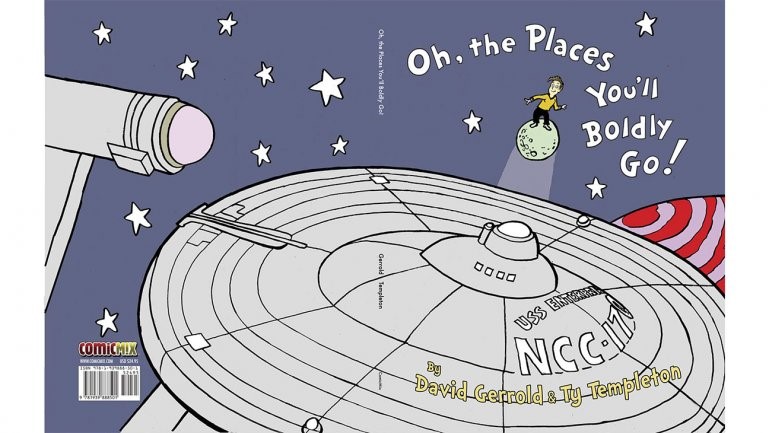

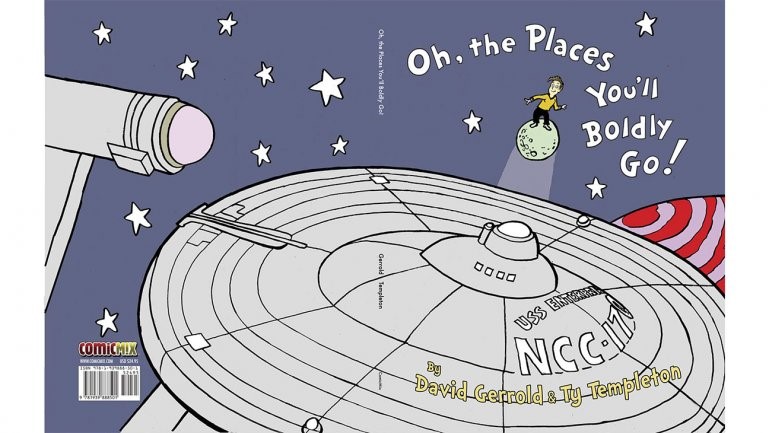

Here is the "parody" cover.

Here is the "parody" cover.

Is there any less of a taking than with "The Cat NOT in the Hat"? The artistic style of Dr. Seuss is clearly imitated, as is the type-face, the positioning of the letters and the figure, who is a boy in the Dr. Seuss book, but is obviously intended to be Captain Kirk in the parody version.

Recall that the Ninth Circuit ruled:

"Parody is regarded as a form of social and literary criticism, having a socially significant value as free speech under the First Amendment. This court has adopted the "conjure up" test where the parodist is permitted a fair use of a copyrighted work if it takes no more than is necessary to "recall" or "conjure up" the object of his parody."

And how much did the authors of "Oh, the Places You'll Boldly Go!" take?

Everything they could.

"[E]ach Defendant also testified that he copied from the Copyrighted Works to create Boldly. (citation omitted) Indeed, Mr. Hauman scanned a copy of Go! to Mr. Gerrold because he wanted to ‘parallel [Go!] as close as [he] c[ould].' (citation omitted) Although Mr. Gerrold had written his first draft ‘from scratch' and without access to Go!, he later rewrote Boldly's text to more closely match Go! (citation omitted) Mr. Hauman created a side-by-side comparison of Go!'s and Boldly's text, (citation omitted) to assist himself and Mr. Gerrold in their effort "to parallel the structure of [Go!]."[ref]Dr. Seuss Enterprises L.P. v. ComicMix LLC at 5[/ref]

"Mr. Templeton's illustration of one page took him about seven hours because he ‘painstakingly attempted to make' his illustration ‘nearly identical' in certain respects to one illustrated by Dr. Seuss. (citation omitted) Mr. Hauman instructed Mr. Templeton to ‘go closer to' Go!, (citation omitted) and Mr. Templeton later admitted, ‘I did, in fact, slavishly copy from Seuss,' to illustrate Boldly."[ref]Id. at 6[/ref]

Yet, the District Court finds that the writers behind "Boldly did not "copy more than is necessary to accomplish its transformative purpose."[ref]Id. at 19[/ref]

How does this square with the ruling of the Ninth Circuit? They ruled:

"As for the objective analysis of expression, the district court's preliminary injunction was granted based on the back cover illustration and the Cat's Hat, not the typeface, poetic meter, whimsical style or visual style. For these reasons, we conclude that the court's findings that Penguin and Dove infringed on Seuss' copyrights are not clearly erroneous."[ref]109 F.3d 1394 at 1399[/ref]

So the copying of the distinctive hat of "The Cat in the Hat" and the back cover is sufficient to support a finding of copyright infringement, but the "slavish copying" of the entire book of Dr. Seuss, is not infringing? How does the District Court get there?

It gets there by ignoring the 9th Circuit decision in "The Cat NOT in the Hat." The case is never mentioned in the District Court opinion. Instead, the Court reaches out to a Second Circuit case, Leibovitz v. Paramount Pictures,[ref]137 F.3d 109 , 2nd Circuit 1998[/ref] for its analysis of what amounts to "too much" of a taking.

Now the District Court is certainly aware of Ninth Circuit decision in "The Cat NOT in the Hat." It was cited in the parties' briefs and cited by the Court itself in its prior opinion.[ref]Oh, The Places You'll Go... But Not There! Dr. Seuss Mash-Up Not Fair Use[/ref]

I simply cannot reconcile the two cases, especially where the target of the parody, Dr. Seuss, is identical in each case.

Remember, the Ninth Circuit ruled this:

"These stanzas and the illustrations simply retell the Simpson tale. Although The Cat NOT in the Hat! does broadly mimic Dr. Seuss' characteristic style, it does not hold his style up to ridicule. The stanzas have ‘no critical bearing on the substance or style of ‘The Cat in the Hat.'"[ref]109 F.3d 1394 at 1401[/ref]

The District Court ruled this:

"'[T]here is no dispute that Boldly copies many aspects of Go!'s and other Dr. Seuss illustrations[,] . . . Boldly does not copy them in their entirety[,]' but rather ‘infuse[s each] with new meaning and additional illustrations that reframe Seuss images from a unique Star-Trek viewpoint.'"[ref]Dr. Seuss Enterprises L.P. v. ComicMix LLC at 19[/ref]

OK. But what does this say about Dr. Seuss?

And there's this by the District Court:

"Here, by contrast, Defendants took discrete elements of the Copyrighted Works: cross-hatching, object placements, certain distinctive facial features, lines written in anapestic tetrameter. Yes, these are elements significant to the Copyrighted Works, but Defendants ultimately did not use Dr. Seuss' words, his character, or his universe."[ref]Id. at 23[/ref]

Except for the hat, neither did "The Cat NOT in the Hat" defendants. But their work is infringing, and Boldly is not.

Also recall on the issues of market substitution, the Ninth Circuit ruled:

"The good will and reputation associated with Dr. Seuss' work is substantial. Because, on the facts presented, Penguin and Dove's use of The Cat in the Hat original was non-transformative, and admittedly commercial, we conclude that market substitution is at least more certain, and market harm may be more readily inferred."[ref]109 F.3d 1394 at 1403[/ref]

Yet the District Court rules that:

"Even viewing the undisputed evidence most favorably to Plaintiff, the Court concludes that Plaintiff has failed to sustain its burden to demonstrate by a preponderance of the evidence that Boldly is likely substantially to harm the market for Go! or licensed derivatives of Go! Instead, the "potential harm to [Plaintiff]'s market remains hypothetical."[ref]Dr. Seuss Enterprises L.P. v. ComicMix LLC at 24[/ref]

The Ninth Circuit ruled that market harms can be "readily inferred." The District Court waives this away as being "hypothetical."

So, once again, we have the magical tail of "transformative use" wagging the fair use dog. But I think there's something else at play here.

The Ninth Circuit, needlessly, and in an endnote states the following:

"Our analysis does not take into account whether The Cat NOT in the Hat! is in good or bad taste. As Justice Holmes explained, ‘[i]t would be a dangerous undertaking for persons trained only to the law to constitute themselves final judges of the worth of [a work], outside of the narrowest and most obvious limits.'"[ref]109 F.3d 1394 at endnote 8[/ref]

As Shakespeare once observed, "methinks they doth protest too much." I think the Ninth Circuit as well as the District Court, found "The Cat NOT in the Hat" to be in very poor taste, and slammed them accordingly.

One thing is for sure, Dr. Seuss Enterprises is certainly wealthy enough, and litigious enough, to make an appeal almost inevitable.

And then we'll get the Ninth Circuit to reconcile these two cases.

It should make for very interesting reading.

Is there any less of a taking than with "The Cat NOT in the Hat"? The artistic style of Dr. Seuss is clearly imitated, as is the type-face, the positioning of the letters and the figure, who is a boy in the Dr. Seuss book, but is obviously intended to be Captain Kirk in the parody version.

Recall that the Ninth Circuit ruled:

"Parody is regarded as a form of social and literary criticism, having a socially significant value as free speech under the First Amendment. This court has adopted the "conjure up" test where the parodist is permitted a fair use of a copyrighted work if it takes no more than is necessary to "recall" or "conjure up" the object of his parody."

And how much did the authors of "Oh, the Places You'll Boldly Go!" take?

Everything they could.

"[E]ach Defendant also testified that he copied from the Copyrighted Works to create Boldly. (citation omitted) Indeed, Mr. Hauman scanned a copy of Go! to Mr. Gerrold because he wanted to ‘parallel [Go!] as close as [he] c[ould].' (citation omitted) Although Mr. Gerrold had written his first draft ‘from scratch' and without access to Go!, he later rewrote Boldly's text to more closely match Go! (citation omitted) Mr. Hauman created a side-by-side comparison of Go!'s and Boldly's text, (citation omitted) to assist himself and Mr. Gerrold in their effort "to parallel the structure of [Go!]."[ref]Dr. Seuss Enterprises L.P. v. ComicMix LLC at 5[/ref]

"Mr. Templeton's illustration of one page took him about seven hours because he ‘painstakingly attempted to make' his illustration ‘nearly identical' in certain respects to one illustrated by Dr. Seuss. (citation omitted) Mr. Hauman instructed Mr. Templeton to ‘go closer to' Go!, (citation omitted) and Mr. Templeton later admitted, ‘I did, in fact, slavishly copy from Seuss,' to illustrate Boldly."[ref]Id. at 6[/ref]

Yet, the District Court finds that the writers behind "Boldly did not "copy more than is necessary to accomplish its transformative purpose."[ref]Id. at 19[/ref]

How does this square with the ruling of the Ninth Circuit? They ruled:

"As for the objective analysis of expression, the district court's preliminary injunction was granted based on the back cover illustration and the Cat's Hat, not the typeface, poetic meter, whimsical style or visual style. For these reasons, we conclude that the court's findings that Penguin and Dove infringed on Seuss' copyrights are not clearly erroneous."[ref]109 F.3d 1394 at 1399[/ref]

So the copying of the distinctive hat of "The Cat in the Hat" and the back cover is sufficient to support a finding of copyright infringement, but the "slavish copying" of the entire book of Dr. Seuss, is not infringing? How does the District Court get there?

It gets there by ignoring the 9th Circuit decision in "The Cat NOT in the Hat." The case is never mentioned in the District Court opinion. Instead, the Court reaches out to a Second Circuit case, Leibovitz v. Paramount Pictures,[ref]137 F.3d 109 , 2nd Circuit 1998[/ref] for its analysis of what amounts to "too much" of a taking.

Now the District Court is certainly aware of Ninth Circuit decision in "The Cat NOT in the Hat." It was cited in the parties' briefs and cited by the Court itself in its prior opinion.[ref]Oh, The Places You'll Go... But Not There! Dr. Seuss Mash-Up Not Fair Use[/ref]

I simply cannot reconcile the two cases, especially where the target of the parody, Dr. Seuss, is identical in each case.

Remember, the Ninth Circuit ruled this:

"These stanzas and the illustrations simply retell the Simpson tale. Although The Cat NOT in the Hat! does broadly mimic Dr. Seuss' characteristic style, it does not hold his style up to ridicule. The stanzas have ‘no critical bearing on the substance or style of ‘The Cat in the Hat.'"[ref]109 F.3d 1394 at 1401[/ref]

The District Court ruled this:

"'[T]here is no dispute that Boldly copies many aspects of Go!'s and other Dr. Seuss illustrations[,] . . . Boldly does not copy them in their entirety[,]' but rather ‘infuse[s each] with new meaning and additional illustrations that reframe Seuss images from a unique Star-Trek viewpoint.'"[ref]Dr. Seuss Enterprises L.P. v. ComicMix LLC at 19[/ref]

OK. But what does this say about Dr. Seuss?

And there's this by the District Court:

"Here, by contrast, Defendants took discrete elements of the Copyrighted Works: cross-hatching, object placements, certain distinctive facial features, lines written in anapestic tetrameter. Yes, these are elements significant to the Copyrighted Works, but Defendants ultimately did not use Dr. Seuss' words, his character, or his universe."[ref]Id. at 23[/ref]

Except for the hat, neither did "The Cat NOT in the Hat" defendants. But their work is infringing, and Boldly is not.

Also recall on the issues of market substitution, the Ninth Circuit ruled:

"The good will and reputation associated with Dr. Seuss' work is substantial. Because, on the facts presented, Penguin and Dove's use of The Cat in the Hat original was non-transformative, and admittedly commercial, we conclude that market substitution is at least more certain, and market harm may be more readily inferred."[ref]109 F.3d 1394 at 1403[/ref]

Yet the District Court rules that:

"Even viewing the undisputed evidence most favorably to Plaintiff, the Court concludes that Plaintiff has failed to sustain its burden to demonstrate by a preponderance of the evidence that Boldly is likely substantially to harm the market for Go! or licensed derivatives of Go! Instead, the "potential harm to [Plaintiff]'s market remains hypothetical."[ref]Dr. Seuss Enterprises L.P. v. ComicMix LLC at 24[/ref]

The Ninth Circuit ruled that market harms can be "readily inferred." The District Court waives this away as being "hypothetical."

So, once again, we have the magical tail of "transformative use" wagging the fair use dog. But I think there's something else at play here.

The Ninth Circuit, needlessly, and in an endnote states the following:

"Our analysis does not take into account whether The Cat NOT in the Hat! is in good or bad taste. As Justice Holmes explained, ‘[i]t would be a dangerous undertaking for persons trained only to the law to constitute themselves final judges of the worth of [a work], outside of the narrowest and most obvious limits.'"[ref]109 F.3d 1394 at endnote 8[/ref]

As Shakespeare once observed, "methinks they doth protest too much." I think the Ninth Circuit as well as the District Court, found "The Cat NOT in the Hat" to be in very poor taste, and slammed them accordingly.

One thing is for sure, Dr. Seuss Enterprises is certainly wealthy enough, and litigious enough, to make an appeal almost inevitable.

And then we'll get the Ninth Circuit to reconcile these two cases.

It should make for very interesting reading.

- The Judge had previously ruled on the Defendant's Motion to Dismiss that "fair use" had not been conclusively demonstrated.[ref]Oh, The Places You'll Go... But Not There! Dr. Seuss Mash-Up Not Fair Use[/ref]

- Ruled "Oh the Places You'll Boldly Go" was not a parody.[ref]Dr. Seuss Enterprises L.P. v. ComicMix LLC at 16[/ref]

- Ruled "Oh the Places You'll Boldly Go" was not a derivative work.[ref]Id. at 17[/ref]

- Never discussed a 9th Circuit case, also involving Dr. Seuss Enterprises that seemed to mandate an opposite result.

And here is a side by side comparison of The Cat In the Hat and "Dr. Juice" who is the tongue in cheek author of "The Cat NOT in The Hat."

And here is a side by side comparison of The Cat In the Hat and "Dr. Juice" who is the tongue in cheek author of "The Cat NOT in The Hat."

Clearly the intent is to mimic the illustration style of Dr. Seuss. The writing style is also closely imitated.

"The third page reads: "One Knife? / Two Knife? / Red Knife / Dead Wife." This stanza no doubt mimics the first poem in Dr. Seuss' One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish: "One fish / two fish / red fish / blue fish. Black fish / blue fish / old fish / new fish."[ref]Id. at 1401[/ref]

But the extent of the imitation is very slight. Oddly enough, this works against the Defendants.

"These stanzas and the illustrations simply retell the Simpson tale. Although The Cat NOT in the Hat! does broadly mimic Dr. Seuss' characteristic style, it does not hold his style up to ridicule. The stanzas have ‘no critical bearing on the substance or style of' The Cat in the Hat."[ref]Id.[/ref]

"The district court concluded that "The Cat in the Hat" is the central character, appearing in nearly every image of The Cat in the Hat. Penguin and Dove appropriated the Cat's image, copying the Cat's Hat and using the image on the front and back covers and in the text (13 times). We have no doubt that the Cat's image is the highly expressive core of Dr. Seuss' work."[ref]Id. at 1402[/ref]

The Ninth Circuit finally concludes:

"The good will and reputation associated with Dr. Seuss' work is substantial. Because, on the facts presented, Penguin and Dove's use of The Cat in the Hat original was non-transformative, and admittedly commercial, we conclude that market substitution is at least more certain, and market harm may be more readily inferred."[ref]Id. at 1403[/ref]

The last part is really curious. Would you really give a six year old "The Cat NOT in the Hat," instead of the "The Cat in the Hat"? I sincerely doubt it. Also notice that the Court is going to infer market harm on a book that is not being currently sold or distributed because it is subject to a preliminary injunction.[ref]Id. at 1397[/ref]

So now, let us turn to "Oh The Places You'll Boldly Go!"

Here is the original Dr. Seuss Cover:

Clearly the intent is to mimic the illustration style of Dr. Seuss. The writing style is also closely imitated.

"The third page reads: "One Knife? / Two Knife? / Red Knife / Dead Wife." This stanza no doubt mimics the first poem in Dr. Seuss' One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish: "One fish / two fish / red fish / blue fish. Black fish / blue fish / old fish / new fish."[ref]Id. at 1401[/ref]

But the extent of the imitation is very slight. Oddly enough, this works against the Defendants.

"These stanzas and the illustrations simply retell the Simpson tale. Although The Cat NOT in the Hat! does broadly mimic Dr. Seuss' characteristic style, it does not hold his style up to ridicule. The stanzas have ‘no critical bearing on the substance or style of' The Cat in the Hat."[ref]Id.[/ref]

"The district court concluded that "The Cat in the Hat" is the central character, appearing in nearly every image of The Cat in the Hat. Penguin and Dove appropriated the Cat's image, copying the Cat's Hat and using the image on the front and back covers and in the text (13 times). We have no doubt that the Cat's image is the highly expressive core of Dr. Seuss' work."[ref]Id. at 1402[/ref]

The Ninth Circuit finally concludes:

"The good will and reputation associated with Dr. Seuss' work is substantial. Because, on the facts presented, Penguin and Dove's use of The Cat in the Hat original was non-transformative, and admittedly commercial, we conclude that market substitution is at least more certain, and market harm may be more readily inferred."[ref]Id. at 1403[/ref]

The last part is really curious. Would you really give a six year old "The Cat NOT in the Hat," instead of the "The Cat in the Hat"? I sincerely doubt it. Also notice that the Court is going to infer market harm on a book that is not being currently sold or distributed because it is subject to a preliminary injunction.[ref]Id. at 1397[/ref]

So now, let us turn to "Oh The Places You'll Boldly Go!"

Here is the original Dr. Seuss Cover:

Here is the "parody" cover.

Here is the "parody" cover.

Is there any less of a taking than with "The Cat NOT in the Hat"? The artistic style of Dr. Seuss is clearly imitated, as is the type-face, the positioning of the letters and the figure, who is a boy in the Dr. Seuss book, but is obviously intended to be Captain Kirk in the parody version.

Recall that the Ninth Circuit ruled:

"Parody is regarded as a form of social and literary criticism, having a socially significant value as free speech under the First Amendment. This court has adopted the "conjure up" test where the parodist is permitted a fair use of a copyrighted work if it takes no more than is necessary to "recall" or "conjure up" the object of his parody."

And how much did the authors of "Oh, the Places You'll Boldly Go!" take?

Everything they could.

"[E]ach Defendant also testified that he copied from the Copyrighted Works to create Boldly. (citation omitted) Indeed, Mr. Hauman scanned a copy of Go! to Mr. Gerrold because he wanted to ‘parallel [Go!] as close as [he] c[ould].' (citation omitted) Although Mr. Gerrold had written his first draft ‘from scratch' and without access to Go!, he later rewrote Boldly's text to more closely match Go! (citation omitted) Mr. Hauman created a side-by-side comparison of Go!'s and Boldly's text, (citation omitted) to assist himself and Mr. Gerrold in their effort "to parallel the structure of [Go!]."[ref]Dr. Seuss Enterprises L.P. v. ComicMix LLC at 5[/ref]

"Mr. Templeton's illustration of one page took him about seven hours because he ‘painstakingly attempted to make' his illustration ‘nearly identical' in certain respects to one illustrated by Dr. Seuss. (citation omitted) Mr. Hauman instructed Mr. Templeton to ‘go closer to' Go!, (citation omitted) and Mr. Templeton later admitted, ‘I did, in fact, slavishly copy from Seuss,' to illustrate Boldly."[ref]Id. at 6[/ref]

Yet, the District Court finds that the writers behind "Boldly did not "copy more than is necessary to accomplish its transformative purpose."[ref]Id. at 19[/ref]

How does this square with the ruling of the Ninth Circuit? They ruled:

"As for the objective analysis of expression, the district court's preliminary injunction was granted based on the back cover illustration and the Cat's Hat, not the typeface, poetic meter, whimsical style or visual style. For these reasons, we conclude that the court's findings that Penguin and Dove infringed on Seuss' copyrights are not clearly erroneous."[ref]109 F.3d 1394 at 1399[/ref]

So the copying of the distinctive hat of "The Cat in the Hat" and the back cover is sufficient to support a finding of copyright infringement, but the "slavish copying" of the entire book of Dr. Seuss, is not infringing? How does the District Court get there?

It gets there by ignoring the 9th Circuit decision in "The Cat NOT in the Hat." The case is never mentioned in the District Court opinion. Instead, the Court reaches out to a Second Circuit case, Leibovitz v. Paramount Pictures,[ref]137 F.3d 109 , 2nd Circuit 1998[/ref] for its analysis of what amounts to "too much" of a taking.

Now the District Court is certainly aware of Ninth Circuit decision in "The Cat NOT in the Hat." It was cited in the parties' briefs and cited by the Court itself in its prior opinion.[ref]Oh, The Places You'll Go... But Not There! Dr. Seuss Mash-Up Not Fair Use[/ref]

I simply cannot reconcile the two cases, especially where the target of the parody, Dr. Seuss, is identical in each case.

Remember, the Ninth Circuit ruled this:

"These stanzas and the illustrations simply retell the Simpson tale. Although The Cat NOT in the Hat! does broadly mimic Dr. Seuss' characteristic style, it does not hold his style up to ridicule. The stanzas have ‘no critical bearing on the substance or style of ‘The Cat in the Hat.'"[ref]109 F.3d 1394 at 1401[/ref]

The District Court ruled this:

"'[T]here is no dispute that Boldly copies many aspects of Go!'s and other Dr. Seuss illustrations[,] . . . Boldly does not copy them in their entirety[,]' but rather ‘infuse[s each] with new meaning and additional illustrations that reframe Seuss images from a unique Star-Trek viewpoint.'"[ref]Dr. Seuss Enterprises L.P. v. ComicMix LLC at 19[/ref]

OK. But what does this say about Dr. Seuss?

And there's this by the District Court:

"Here, by contrast, Defendants took discrete elements of the Copyrighted Works: cross-hatching, object placements, certain distinctive facial features, lines written in anapestic tetrameter. Yes, these are elements significant to the Copyrighted Works, but Defendants ultimately did not use Dr. Seuss' words, his character, or his universe."[ref]Id. at 23[/ref]

Except for the hat, neither did "The Cat NOT in the Hat" defendants. But their work is infringing, and Boldly is not.

Also recall on the issues of market substitution, the Ninth Circuit ruled:

"The good will and reputation associated with Dr. Seuss' work is substantial. Because, on the facts presented, Penguin and Dove's use of The Cat in the Hat original was non-transformative, and admittedly commercial, we conclude that market substitution is at least more certain, and market harm may be more readily inferred."[ref]109 F.3d 1394 at 1403[/ref]

Yet the District Court rules that:

"Even viewing the undisputed evidence most favorably to Plaintiff, the Court concludes that Plaintiff has failed to sustain its burden to demonstrate by a preponderance of the evidence that Boldly is likely substantially to harm the market for Go! or licensed derivatives of Go! Instead, the "potential harm to [Plaintiff]'s market remains hypothetical."[ref]Dr. Seuss Enterprises L.P. v. ComicMix LLC at 24[/ref]

The Ninth Circuit ruled that market harms can be "readily inferred." The District Court waives this away as being "hypothetical."

So, once again, we have the magical tail of "transformative use" wagging the fair use dog. But I think there's something else at play here.

The Ninth Circuit, needlessly, and in an endnote states the following:

"Our analysis does not take into account whether The Cat NOT in the Hat! is in good or bad taste. As Justice Holmes explained, ‘[i]t would be a dangerous undertaking for persons trained only to the law to constitute themselves final judges of the worth of [a work], outside of the narrowest and most obvious limits.'"[ref]109 F.3d 1394 at endnote 8[/ref]

As Shakespeare once observed, "methinks they doth protest too much." I think the Ninth Circuit as well as the District Court, found "The Cat NOT in the Hat" to be in very poor taste, and slammed them accordingly.

One thing is for sure, Dr. Seuss Enterprises is certainly wealthy enough, and litigious enough, to make an appeal almost inevitable.

And then we'll get the Ninth Circuit to reconcile these two cases.

It should make for very interesting reading.

Is there any less of a taking than with "The Cat NOT in the Hat"? The artistic style of Dr. Seuss is clearly imitated, as is the type-face, the positioning of the letters and the figure, who is a boy in the Dr. Seuss book, but is obviously intended to be Captain Kirk in the parody version.

Recall that the Ninth Circuit ruled:

"Parody is regarded as a form of social and literary criticism, having a socially significant value as free speech under the First Amendment. This court has adopted the "conjure up" test where the parodist is permitted a fair use of a copyrighted work if it takes no more than is necessary to "recall" or "conjure up" the object of his parody."

And how much did the authors of "Oh, the Places You'll Boldly Go!" take?

Everything they could.

"[E]ach Defendant also testified that he copied from the Copyrighted Works to create Boldly. (citation omitted) Indeed, Mr. Hauman scanned a copy of Go! to Mr. Gerrold because he wanted to ‘parallel [Go!] as close as [he] c[ould].' (citation omitted) Although Mr. Gerrold had written his first draft ‘from scratch' and without access to Go!, he later rewrote Boldly's text to more closely match Go! (citation omitted) Mr. Hauman created a side-by-side comparison of Go!'s and Boldly's text, (citation omitted) to assist himself and Mr. Gerrold in their effort "to parallel the structure of [Go!]."[ref]Dr. Seuss Enterprises L.P. v. ComicMix LLC at 5[/ref]

"Mr. Templeton's illustration of one page took him about seven hours because he ‘painstakingly attempted to make' his illustration ‘nearly identical' in certain respects to one illustrated by Dr. Seuss. (citation omitted) Mr. Hauman instructed Mr. Templeton to ‘go closer to' Go!, (citation omitted) and Mr. Templeton later admitted, ‘I did, in fact, slavishly copy from Seuss,' to illustrate Boldly."[ref]Id. at 6[/ref]

Yet, the District Court finds that the writers behind "Boldly did not "copy more than is necessary to accomplish its transformative purpose."[ref]Id. at 19[/ref]

How does this square with the ruling of the Ninth Circuit? They ruled:

"As for the objective analysis of expression, the district court's preliminary injunction was granted based on the back cover illustration and the Cat's Hat, not the typeface, poetic meter, whimsical style or visual style. For these reasons, we conclude that the court's findings that Penguin and Dove infringed on Seuss' copyrights are not clearly erroneous."[ref]109 F.3d 1394 at 1399[/ref]

So the copying of the distinctive hat of "The Cat in the Hat" and the back cover is sufficient to support a finding of copyright infringement, but the "slavish copying" of the entire book of Dr. Seuss, is not infringing? How does the District Court get there?

It gets there by ignoring the 9th Circuit decision in "The Cat NOT in the Hat." The case is never mentioned in the District Court opinion. Instead, the Court reaches out to a Second Circuit case, Leibovitz v. Paramount Pictures,[ref]137 F.3d 109 , 2nd Circuit 1998[/ref] for its analysis of what amounts to "too much" of a taking.

Now the District Court is certainly aware of Ninth Circuit decision in "The Cat NOT in the Hat." It was cited in the parties' briefs and cited by the Court itself in its prior opinion.[ref]Oh, The Places You'll Go... But Not There! Dr. Seuss Mash-Up Not Fair Use[/ref]

I simply cannot reconcile the two cases, especially where the target of the parody, Dr. Seuss, is identical in each case.

Remember, the Ninth Circuit ruled this:

"These stanzas and the illustrations simply retell the Simpson tale. Although The Cat NOT in the Hat! does broadly mimic Dr. Seuss' characteristic style, it does not hold his style up to ridicule. The stanzas have ‘no critical bearing on the substance or style of ‘The Cat in the Hat.'"[ref]109 F.3d 1394 at 1401[/ref]

The District Court ruled this:

"'[T]here is no dispute that Boldly copies many aspects of Go!'s and other Dr. Seuss illustrations[,] . . . Boldly does not copy them in their entirety[,]' but rather ‘infuse[s each] with new meaning and additional illustrations that reframe Seuss images from a unique Star-Trek viewpoint.'"[ref]Dr. Seuss Enterprises L.P. v. ComicMix LLC at 19[/ref]

OK. But what does this say about Dr. Seuss?

And there's this by the District Court:

"Here, by contrast, Defendants took discrete elements of the Copyrighted Works: cross-hatching, object placements, certain distinctive facial features, lines written in anapestic tetrameter. Yes, these are elements significant to the Copyrighted Works, but Defendants ultimately did not use Dr. Seuss' words, his character, or his universe."[ref]Id. at 23[/ref]

Except for the hat, neither did "The Cat NOT in the Hat" defendants. But their work is infringing, and Boldly is not.

Also recall on the issues of market substitution, the Ninth Circuit ruled:

"The good will and reputation associated with Dr. Seuss' work is substantial. Because, on the facts presented, Penguin and Dove's use of The Cat in the Hat original was non-transformative, and admittedly commercial, we conclude that market substitution is at least more certain, and market harm may be more readily inferred."[ref]109 F.3d 1394 at 1403[/ref]

Yet the District Court rules that:

"Even viewing the undisputed evidence most favorably to Plaintiff, the Court concludes that Plaintiff has failed to sustain its burden to demonstrate by a preponderance of the evidence that Boldly is likely substantially to harm the market for Go! or licensed derivatives of Go! Instead, the "potential harm to [Plaintiff]'s market remains hypothetical."[ref]Dr. Seuss Enterprises L.P. v. ComicMix LLC at 24[/ref]

The Ninth Circuit ruled that market harms can be "readily inferred." The District Court waives this away as being "hypothetical."

So, once again, we have the magical tail of "transformative use" wagging the fair use dog. But I think there's something else at play here.

The Ninth Circuit, needlessly, and in an endnote states the following:

"Our analysis does not take into account whether The Cat NOT in the Hat! is in good or bad taste. As Justice Holmes explained, ‘[i]t would be a dangerous undertaking for persons trained only to the law to constitute themselves final judges of the worth of [a work], outside of the narrowest and most obvious limits.'"[ref]109 F.3d 1394 at endnote 8[/ref]

As Shakespeare once observed, "methinks they doth protest too much." I think the Ninth Circuit as well as the District Court, found "The Cat NOT in the Hat" to be in very poor taste, and slammed them accordingly.

One thing is for sure, Dr. Seuss Enterprises is certainly wealthy enough, and litigious enough, to make an appeal almost inevitable.

And then we'll get the Ninth Circuit to reconcile these two cases.

It should make for very interesting reading.