On July 30, 2019, a Federal Jury returned a verdict that Katy Perry, along with co-writers Jordan Houston (p/k/a Juicy J) Lukasz Gottwald (p/k/a Dr. Luke) Sarah Hudson, Max Martin and Henry Walter (p/k/a Cirkut)[ref]Dark Horse (Katy Perry song)[/ref] were all guilty of copyright infringement.[ref]A jury said Katy Perry's "Dark Horse" copied another song. The $2.8 million verdict is alarming.[/ref] Then, on August 1, 2019, that same jury decided that:

"…Ms. Perry must pay $550,000, while her label, Capitol Records, owes nearly $1.3 million. Ms. Perry's five collaborators in writing the song were also ordered to pay, including the star producers Max Martin, who owes $253,000, and Dr. Luke, who owes $61,000 personally, while his company, Kasz Money Inc., owes $189,000."[ref]Katy Perry and Others Must Pay $2.8 Million Over 'Dark Horse,' Jury Says[/ref]

The criticism was quick and unyielding.

"The [offending melody is] a starkly simple phrase, six descending notes that a marginally talented toddler could bang out on a toy xylophone."[ref]Katy Perry's 'Dark Horse' Case and Its Chilling Effect on Songwriting[/ref]

"…Charlie Harding of the Vox podcast Switched on Pop explains that the striking similarities should be free to use by both artists, despite their similarities. Both "Joyful Noise" and "Dark Horse" use derivative descending minor scales in a basic rhythm, Harding said, and both use staccato downbeat rhythms on a high voiced synthesizer which is common in many trap beats.

Harding also says the songs are in different keys and BPMs (beats per minute), and that the melodies are not the same notes."[ref]A jury said Katy Perry's "Dark Horse" copied another song. The $2.8 million verdict is alarming.[/ref]

Here are the two songs so you can compare for yourself:

Here's Plaintiff's song, "Joyful Noise":

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=1&v=jTLeHuvHXuk[/embed]

Here's Defendant's Song, "Dark Horse":

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0KSOMA3QBU0[/embed]

Even on a first listen, the beds of the songs are very similar. But just how similar are they?

First, let's take on the criticism that "the songs are in different keys." From a music theory standpoint, this does not matter. As long as the two keys remain of the same type (major, minor etc.), the relationship between the notes and the most important notes in the scale (the tonic, sub-dominant and dominant) remain the same. We will talk more about this later.

In addition, that the songs have different tempos, expressed above as "beats per minute," also does not matter. If it's the same song, it's the same song, no matter how fast or slow it is played. The version of "You Keep Me Hangin' On" by the Vanilla Fudge is the same song as "You Keep Me Hangin' On" by The Supremes, in spite of the vastly different tempos.

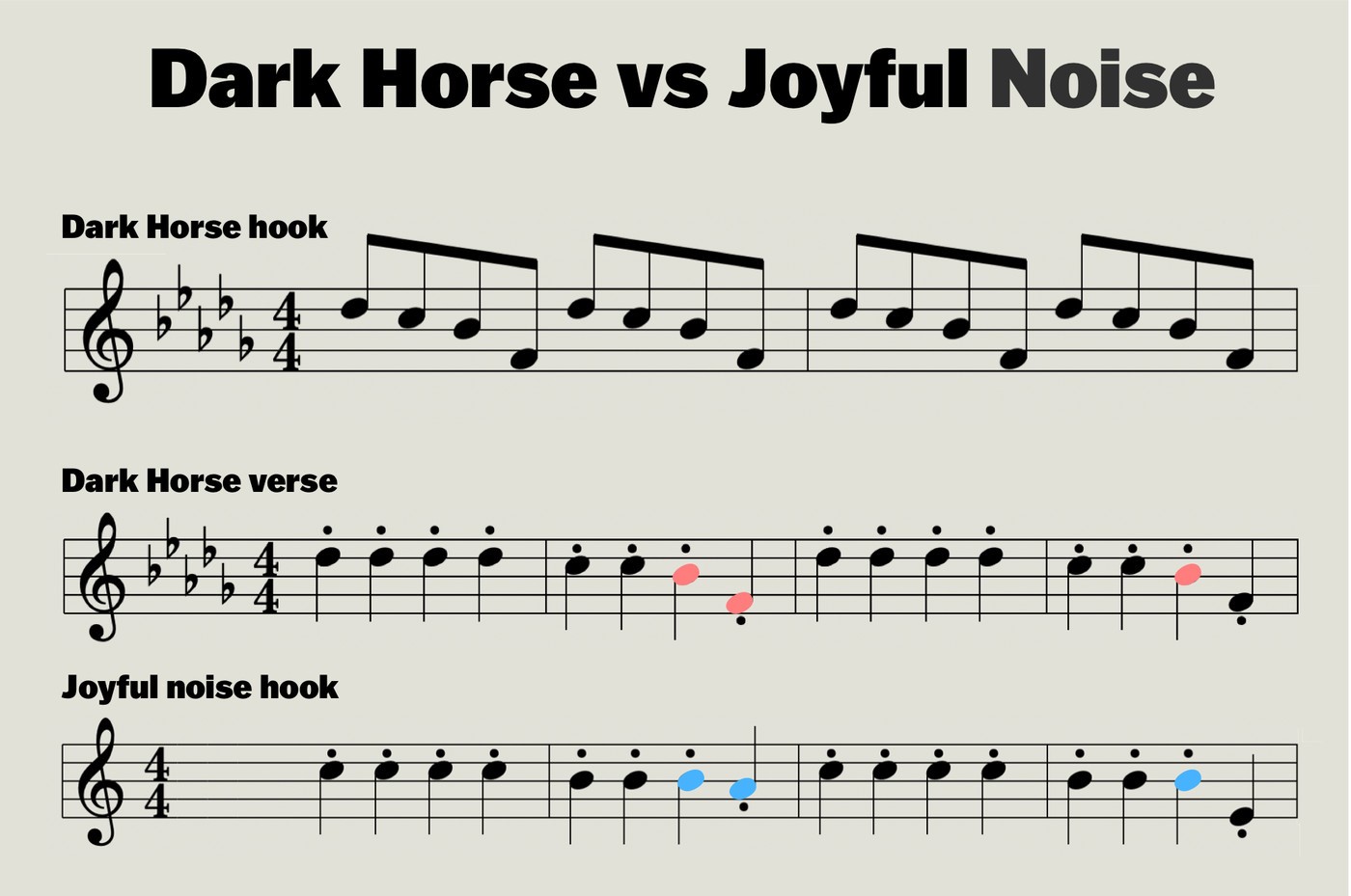

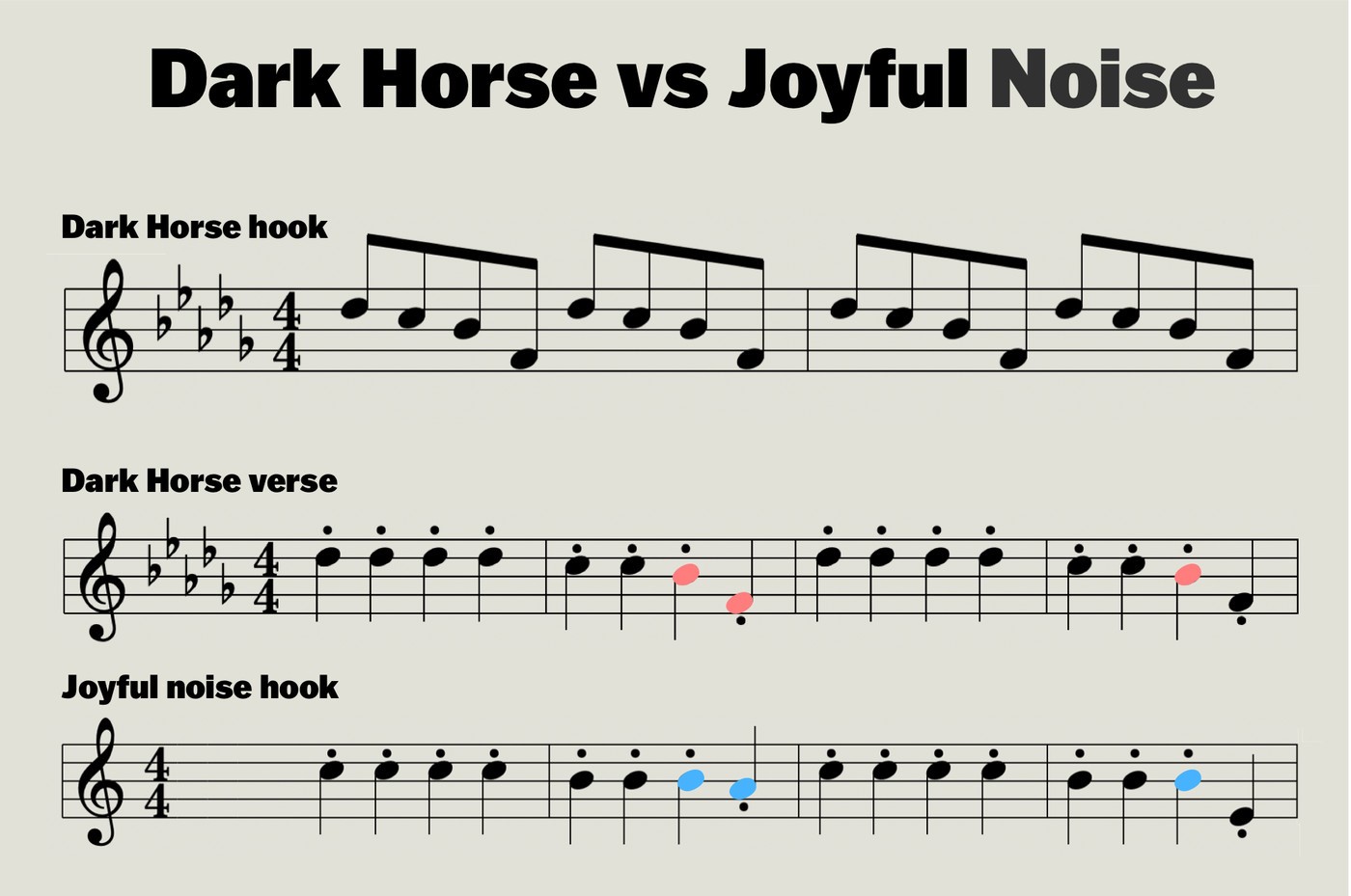

If you read music, Vox.com has a transcription of the two songs.[ref]A jury said Katy Perry's "Dark Horse" copied another song. The $2.8 million verdict is alarming.[/ref] All thanks and credit to them. The differences between JN and DH are reflected in color. The similarities are noted by black notes. Just from a visual sense you can readily observe that the two songs are very similar.

Even though I'm afraid I'm about to lose 70% of my readership, here goes:

The first six notes of both JN and DH are exactly the same, when you take into account the harmonic relationship to the key the song is in. DH is in D flat major. JN is in C major.

The first four notes of JN are the note C played in quarter notes. In music theory this is called the "tonic note" or the note that starts the musical scale. The next two notes are the note B also played in quarter-notes, which is the note immediately adjacent to C, or what music theory calls a "half-step."

"Dark Horse" does the exact same thing. The first four notes are the tonic D flat in quarter-notes with the next two notes being a half-step down, or the note C, also in quarter notes.

Now let's look at the last two bars of each songs' phrase. The phrases are identical except for one note. The last two notes of JN are B and E. The last two notes of DH are B flat and F. In JN this would be a distance of a half –step and a minor 6th. In DH this would be a distance of a minor 3rd and a minor 6th. So, in each case the first four notes are the tonic, the next two notes are a half-step down and the final note is the exact same harmonic distance, a minor 6th.

So in sum, out of the 16 notes in each phrase, only three notes are different harmonically, and the rhythm of the notes is exactly the same. And in the third bar, while the final note in JN is a minor 3rd apart (A), and while in DH a minor 6th apart in (F), in harmony terms, this is not a big difference. The 3rd or the 6th notes of a major scale are very similar in their harmonic effect and are considered "tonic substitutes."

Now, the phrase that is in dispute is not exactly a Beethoven symphony. Like "Stairway to Heaven" before it, it has musical predecessors that sound very similar. Take, for example, this song from the band "Art of Noise" titled "Moments in Love":

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=14&v=ux3u31SAeEM[/embed]

The main defense, of course, is that the composers of DH claim to have never heard JN. If this is true, then the doctrine of independent creation comes into play: you can't copy what you have never heard. This is what got the Bee Gees off the hook from a similar shocking verdict over the song "How Deep Is Your Love."

Even though I'm afraid I'm about to lose 70% of my readership, here goes:

The first six notes of both JN and DH are exactly the same, when you take into account the harmonic relationship to the key the song is in. DH is in D flat major. JN is in C major.

The first four notes of JN are the note C played in quarter notes. In music theory this is called the "tonic note" or the note that starts the musical scale. The next two notes are the note B also played in quarter-notes, which is the note immediately adjacent to C, or what music theory calls a "half-step."

"Dark Horse" does the exact same thing. The first four notes are the tonic D flat in quarter-notes with the next two notes being a half-step down, or the note C, also in quarter notes.

Now let's look at the last two bars of each songs' phrase. The phrases are identical except for one note. The last two notes of JN are B and E. The last two notes of DH are B flat and F. In JN this would be a distance of a half –step and a minor 6th. In DH this would be a distance of a minor 3rd and a minor 6th. So, in each case the first four notes are the tonic, the next two notes are a half-step down and the final note is the exact same harmonic distance, a minor 6th.

So in sum, out of the 16 notes in each phrase, only three notes are different harmonically, and the rhythm of the notes is exactly the same. And in the third bar, while the final note in JN is a minor 3rd apart (A), and while in DH a minor 6th apart in (F), in harmony terms, this is not a big difference. The 3rd or the 6th notes of a major scale are very similar in their harmonic effect and are considered "tonic substitutes."

Now, the phrase that is in dispute is not exactly a Beethoven symphony. Like "Stairway to Heaven" before it, it has musical predecessors that sound very similar. Take, for example, this song from the band "Art of Noise" titled "Moments in Love":

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=14&v=ux3u31SAeEM[/embed]

The main defense, of course, is that the composers of DH claim to have never heard JN. If this is true, then the doctrine of independent creation comes into play: you can't copy what you have never heard. This is what got the Bee Gees off the hook from a similar shocking verdict over the song "How Deep Is Your Love."

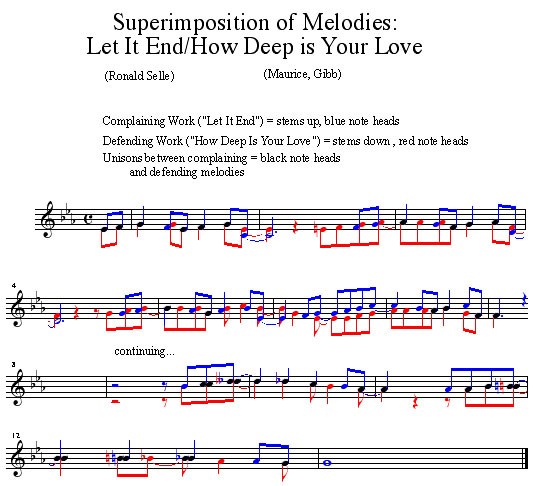

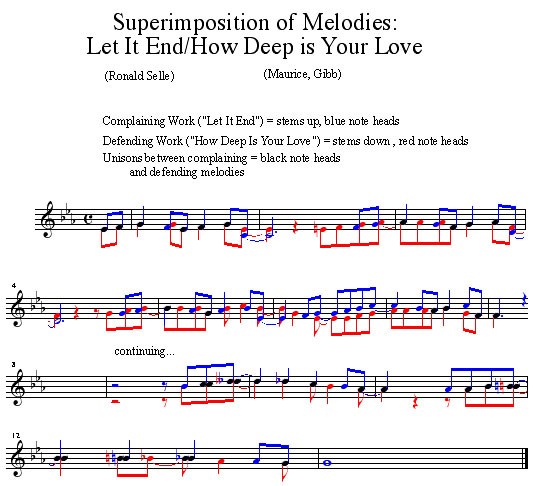

"Look at the first three bars of music. Out of the eight notes played, six are the exact same pitch, and the timing of all the notes is identical. All counted, there are 30 instances of notes sharing the same pitch and time value."[ref]The "Blurred Lines" Verdict: What It Means For Music Now and In the Future[/ref]

Yet, the Plaintiff was unable to prove the Bee Gees had ever heard his song. Beyond sending it to a few music publishers and record companies, the song had no commercial distribution. The trial judge reversed the jury's verdict and the 7th Circuit affirmed.[ref]Selle v. Gibb, 741 F. 2d 896 (7th Cir. 1984)[/ref]

This is not the case with JN. The song was widely distributed. It had 5 million YouTube views.[ref]Katy Perry Loses 'Dark Horse' Copyright Trial[/ref] The album which contained JN was nominated for a Grammy.[ref]Id.[/ref] The song itself was nominated for a Gospel Music Award.[ref]Flame (rapper)[/ref]

The problem here is that the songs, when taken at their totality, are very different and not substantially similar. After all, JN is a rap song, and DH is most certainly not a rap song.

Yet, countering that, is that the parts that are similar, are nearly identical. To a jury's ears, this could easily tip the balance, much more so than the similarities that occur in the "Blurred Lines" case.[ref]The "Blurred Lines" Verdict: What It Means For Music Now and In the Future[/ref]

And then there's this.

Go back and listen to the opening seconds of each song. At the 00:11 mark of JN, a male voice shouts out "You know what it is?"

At the 00:11 mark of DH, a male voice shouts out "Y'all know what it is?"

Now if the Defendants had never heard the song "Joyful Noise," how the heck did that happen?

"Look at the first three bars of music. Out of the eight notes played, six are the exact same pitch, and the timing of all the notes is identical. All counted, there are 30 instances of notes sharing the same pitch and time value."[ref]The "Blurred Lines" Verdict: What It Means For Music Now and In the Future[/ref]

Yet, the Plaintiff was unable to prove the Bee Gees had ever heard his song. Beyond sending it to a few music publishers and record companies, the song had no commercial distribution. The trial judge reversed the jury's verdict and the 7th Circuit affirmed.[ref]Selle v. Gibb, 741 F. 2d 896 (7th Cir. 1984)[/ref]

This is not the case with JN. The song was widely distributed. It had 5 million YouTube views.[ref]Katy Perry Loses 'Dark Horse' Copyright Trial[/ref] The album which contained JN was nominated for a Grammy.[ref]Id.[/ref] The song itself was nominated for a Gospel Music Award.[ref]Flame (rapper)[/ref]

The problem here is that the songs, when taken at their totality, are very different and not substantially similar. After all, JN is a rap song, and DH is most certainly not a rap song.

Yet, countering that, is that the parts that are similar, are nearly identical. To a jury's ears, this could easily tip the balance, much more so than the similarities that occur in the "Blurred Lines" case.[ref]The "Blurred Lines" Verdict: What It Means For Music Now and In the Future[/ref]

And then there's this.

Go back and listen to the opening seconds of each song. At the 00:11 mark of JN, a male voice shouts out "You know what it is?"

At the 00:11 mark of DH, a male voice shouts out "Y'all know what it is?"

Now if the Defendants had never heard the song "Joyful Noise," how the heck did that happen?

Even though I'm afraid I'm about to lose 70% of my readership, here goes:

The first six notes of both JN and DH are exactly the same, when you take into account the harmonic relationship to the key the song is in. DH is in D flat major. JN is in C major.

The first four notes of JN are the note C played in quarter notes. In music theory this is called the "tonic note" or the note that starts the musical scale. The next two notes are the note B also played in quarter-notes, which is the note immediately adjacent to C, or what music theory calls a "half-step."

"Dark Horse" does the exact same thing. The first four notes are the tonic D flat in quarter-notes with the next two notes being a half-step down, or the note C, also in quarter notes.

Now let's look at the last two bars of each songs' phrase. The phrases are identical except for one note. The last two notes of JN are B and E. The last two notes of DH are B flat and F. In JN this would be a distance of a half –step and a minor 6th. In DH this would be a distance of a minor 3rd and a minor 6th. So, in each case the first four notes are the tonic, the next two notes are a half-step down and the final note is the exact same harmonic distance, a minor 6th.

So in sum, out of the 16 notes in each phrase, only three notes are different harmonically, and the rhythm of the notes is exactly the same. And in the third bar, while the final note in JN is a minor 3rd apart (A), and while in DH a minor 6th apart in (F), in harmony terms, this is not a big difference. The 3rd or the 6th notes of a major scale are very similar in their harmonic effect and are considered "tonic substitutes."

Now, the phrase that is in dispute is not exactly a Beethoven symphony. Like "Stairway to Heaven" before it, it has musical predecessors that sound very similar. Take, for example, this song from the band "Art of Noise" titled "Moments in Love":

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=14&v=ux3u31SAeEM[/embed]

The main defense, of course, is that the composers of DH claim to have never heard JN. If this is true, then the doctrine of independent creation comes into play: you can't copy what you have never heard. This is what got the Bee Gees off the hook from a similar shocking verdict over the song "How Deep Is Your Love."

Even though I'm afraid I'm about to lose 70% of my readership, here goes:

The first six notes of both JN and DH are exactly the same, when you take into account the harmonic relationship to the key the song is in. DH is in D flat major. JN is in C major.

The first four notes of JN are the note C played in quarter notes. In music theory this is called the "tonic note" or the note that starts the musical scale. The next two notes are the note B also played in quarter-notes, which is the note immediately adjacent to C, or what music theory calls a "half-step."

"Dark Horse" does the exact same thing. The first four notes are the tonic D flat in quarter-notes with the next two notes being a half-step down, or the note C, also in quarter notes.

Now let's look at the last two bars of each songs' phrase. The phrases are identical except for one note. The last two notes of JN are B and E. The last two notes of DH are B flat and F. In JN this would be a distance of a half –step and a minor 6th. In DH this would be a distance of a minor 3rd and a minor 6th. So, in each case the first four notes are the tonic, the next two notes are a half-step down and the final note is the exact same harmonic distance, a minor 6th.

So in sum, out of the 16 notes in each phrase, only three notes are different harmonically, and the rhythm of the notes is exactly the same. And in the third bar, while the final note in JN is a minor 3rd apart (A), and while in DH a minor 6th apart in (F), in harmony terms, this is not a big difference. The 3rd or the 6th notes of a major scale are very similar in their harmonic effect and are considered "tonic substitutes."

Now, the phrase that is in dispute is not exactly a Beethoven symphony. Like "Stairway to Heaven" before it, it has musical predecessors that sound very similar. Take, for example, this song from the band "Art of Noise" titled "Moments in Love":

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=14&v=ux3u31SAeEM[/embed]

The main defense, of course, is that the composers of DH claim to have never heard JN. If this is true, then the doctrine of independent creation comes into play: you can't copy what you have never heard. This is what got the Bee Gees off the hook from a similar shocking verdict over the song "How Deep Is Your Love."

"Look at the first three bars of music. Out of the eight notes played, six are the exact same pitch, and the timing of all the notes is identical. All counted, there are 30 instances of notes sharing the same pitch and time value."[ref]The "Blurred Lines" Verdict: What It Means For Music Now and In the Future[/ref]

Yet, the Plaintiff was unable to prove the Bee Gees had ever heard his song. Beyond sending it to a few music publishers and record companies, the song had no commercial distribution. The trial judge reversed the jury's verdict and the 7th Circuit affirmed.[ref]Selle v. Gibb, 741 F. 2d 896 (7th Cir. 1984)[/ref]

This is not the case with JN. The song was widely distributed. It had 5 million YouTube views.[ref]Katy Perry Loses 'Dark Horse' Copyright Trial[/ref] The album which contained JN was nominated for a Grammy.[ref]Id.[/ref] The song itself was nominated for a Gospel Music Award.[ref]Flame (rapper)[/ref]

The problem here is that the songs, when taken at their totality, are very different and not substantially similar. After all, JN is a rap song, and DH is most certainly not a rap song.

Yet, countering that, is that the parts that are similar, are nearly identical. To a jury's ears, this could easily tip the balance, much more so than the similarities that occur in the "Blurred Lines" case.[ref]The "Blurred Lines" Verdict: What It Means For Music Now and In the Future[/ref]

And then there's this.

Go back and listen to the opening seconds of each song. At the 00:11 mark of JN, a male voice shouts out "You know what it is?"

At the 00:11 mark of DH, a male voice shouts out "Y'all know what it is?"

Now if the Defendants had never heard the song "Joyful Noise," how the heck did that happen?

"Look at the first three bars of music. Out of the eight notes played, six are the exact same pitch, and the timing of all the notes is identical. All counted, there are 30 instances of notes sharing the same pitch and time value."[ref]The "Blurred Lines" Verdict: What It Means For Music Now and In the Future[/ref]

Yet, the Plaintiff was unable to prove the Bee Gees had ever heard his song. Beyond sending it to a few music publishers and record companies, the song had no commercial distribution. The trial judge reversed the jury's verdict and the 7th Circuit affirmed.[ref]Selle v. Gibb, 741 F. 2d 896 (7th Cir. 1984)[/ref]

This is not the case with JN. The song was widely distributed. It had 5 million YouTube views.[ref]Katy Perry Loses 'Dark Horse' Copyright Trial[/ref] The album which contained JN was nominated for a Grammy.[ref]Id.[/ref] The song itself was nominated for a Gospel Music Award.[ref]Flame (rapper)[/ref]

The problem here is that the songs, when taken at their totality, are very different and not substantially similar. After all, JN is a rap song, and DH is most certainly not a rap song.

Yet, countering that, is that the parts that are similar, are nearly identical. To a jury's ears, this could easily tip the balance, much more so than the similarities that occur in the "Blurred Lines" case.[ref]The "Blurred Lines" Verdict: What It Means For Music Now and In the Future[/ref]

And then there's this.

Go back and listen to the opening seconds of each song. At the 00:11 mark of JN, a male voice shouts out "You know what it is?"

At the 00:11 mark of DH, a male voice shouts out "Y'all know what it is?"

Now if the Defendants had never heard the song "Joyful Noise," how the heck did that happen?