The Supreme Court's decision in Andy Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith[ref]598 U.S. 508 (2023)[/ref] was a breath of fresh air that provided much needed guidance on the issue of fair use. Moreover, it reigned in the overbroad standard of "transformativeness" that had plagued court decisions for years. Never has this been more apparent than a recent case out of the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals that reversed a District Court finding of fair use. What was notable was that the case is virtually identical, as to the facts, as to the type of work copied, as to the type of use by the Defendant, brought by the exact same Plaintiff, that six years earlier had been found to be fair use.

The recent case is Philpot v. Independent Journal Review,[ref]2024 WL 442066, Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals (2024)[/ref] and the facts are as follows:

- Plaintiff Philpot is a professional photographer whose specialty is concert photos of rock musicians

- He took and registered a photograph of guitarist Ted Nugent and registered same with the Copyright Office

- He made the photo available through a Creative Commons license, which required that all uses provide Philpot with attribution

- Defendant IJR republished the photograph of Nugent to accompany the article "15 Signs Your Daddy Was a Conservative"

- Defendant did not alter the photo except slight cropping to eliminate negative space

- Defendant did not provide the required credit, instead linking to Nugent's Wikipedia page[ref]Id. at 1-2[/ref]

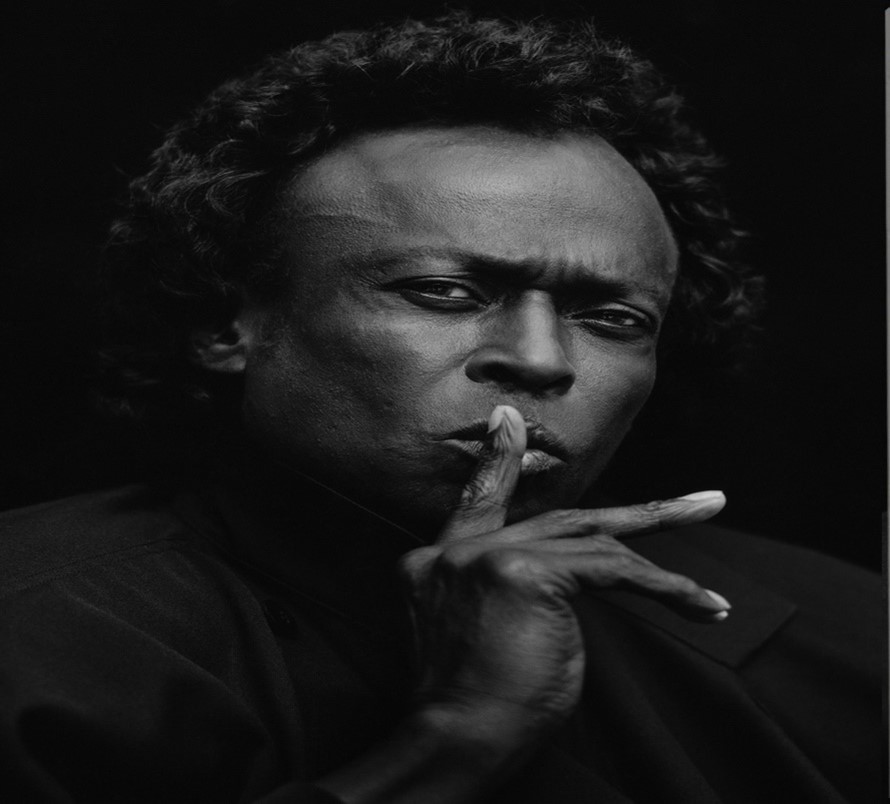

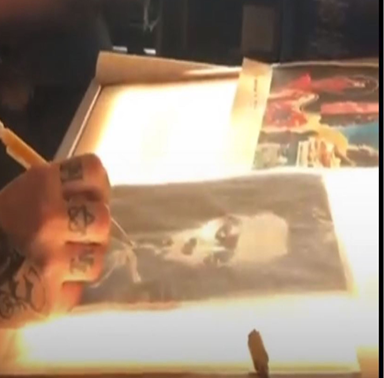

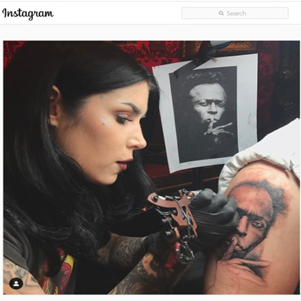

Here is a side-by-side comparison of the photograph and finalized tattoo:

Here is a side-by-side comparison of the photograph and finalized tattoo: